[ad_1]

This time Bulgaria is preventing the start of accession negotiations. “We don’t think it’s time” to start negotiations with Skopje, German Secretary of State for European Affairs Michael Roth – whose country holds the presidency of EU ministerial meetings until the end of the year – said on Tuesday (17 November). a videoconference with its European counterparts.

“Bulgaria cannot support a framework agreement with the Republic of North Macedonia at this stage”, confirmed Bulgarian Foreign Minister Ekaterina Zaharieva. However, this framework agreement can only be adopted unanimously by the 27 EU Member States. Prior to Tuesday’s meeting, Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev said he was ready for such a decision, adding that there was still time to convene the first intergovernmental conference to begin negotiations in late December. But why did this block occur?

A controversy over history and language

Sofia is reviving controversies over linguistic, historical and identity issues that have poisoned North Macedonia since independence three decades ago. The Bulgarian government of Boiko Borisov, in which the VMRO nationalist party participates, has recently sharpened its tone, reproaching Skopje for not wanting to resolve historical disputes and portraying Bulgaria (7 million inhabitants) as an enemy in the media and in books. of history.

According to Bulgaria, the two countries have a common history until the formation of the Republic of Macedonia in Yugoslavia after the Second World War: on this basis, even in the opinion of Bulgaria, the Macedonians are Bulgarians, mistakenly convinced that they have an identity distinguished through a “project” of ethnic construction “of the former Communist Yugoslavia. Furthermore, the concept of Macedonian language is wrong, says Sofia, because it is a Bulgarian dialect.

According to the results of two recent surveys by the Alpha Research Institute, Bulgarian public opinion supports this position: 79% of Bulgarians estimate that Skopje, not recognizing the Bulgarian origins of the Macedonian population, is guilty of “manipulation of historical facts”; and 84% are against Bulgaria which supports North Macedonia’s accession to the EU before a compromise is reached on the interpretation of history.

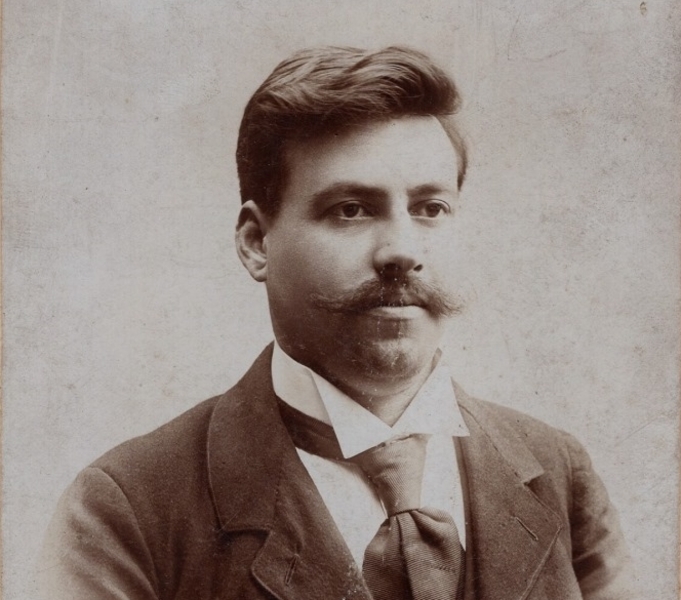

A controversial hero

A bilateral commission of specialists, created in 2017 by the friendship treaty signed between the two countries at the time, is trying to find common ground and harmonize school textbooks. But according to Petar Todorov, a Macedonian historian who is a member of the commission, the meetings were interrupted in 2019 due to the subject of Gote Delcev (1872-1903), a hero of the Ottoman era. Born in present-day Greece, he taught at a Bulgarian school in what is now the Republic of North Macedonia. At the beginning of the twentieth century he entered posterity as a champion of the struggle against the Ottomans. The two countries are vying for his memory.

On both sides of the border there are statues and universities bearing his name and even cities.

“The people here are adamant: Gote Delcev is a historical Bulgarian figure,” Elka Bojikova, director of the high school in the town of the same name … Gote Delcev, in southwestern Bulgaria, told France Presse. “It is a fact that the heroes of the past, such as Delcev’s Goths, are important to both Macedonians and Bulgarians,” North Macedonian Deputy Prime Minister for European Affairs Nikola Dimitrov from Balkan said in September. Insight. “Historians must lean on the argument, also so that each side can know the other’s point of view.”

Internal political stake

What if the historical dispute was just an illusion? According to Angelos Chrisogelos, a contributor to the Chatham House think tank, quoted by Euronews, most of Sofia’s requests to North Macedonia concern unclear questions of identity and history and reflect the need for the Bulgarian government to take a firm nationalist stance. for reasons of internal politics “.

Some analysts denounce a common tactic in the Balkans: recalling historical emotional conflicts to gain points for next year’s elections in Bulgaria. However, since mid-2020, massive protests against the “mafia dictatorship” have shaken the country, the poorest and most corrupt in Europe, according to the NGO Transparency International, and are increasing demands for the resignation of Bulgarian leaders.

Not yet in the EU, but already in NATO

The road to the EU opened for the Republic of Macedonia in January 2019, when the country concluded to reach an agreement with Greece on its name – under the Prespa agreement – by agreeing to add “North”. For 27 years, Greece accused its neighbor of historical abuse using the name “Macedonia” it wanted to keep for its northern province. Athens, a member of the EU, has blocked any rapprochement between Northern Macedonia on the one hand and NATO and Brussels on the other. Once this quarrel subsided, the country became the 30th member of the Atlantic Alliance on March 27.

Bulgaria did not hesitate to evoke the Greek-Macedonian agreement to force the hand of its neighbor. “You agreed to change your flag, to change your name,” Krasimir Karakashanov, the Bulgarian deputy prime minister, according to Euractiv, said in September. The world (Acquisition of Rador)

.

[ad_2]

Source link