[ad_1]

Charles Simkins says it would be a miracle if the sub-continent avoided a serious dislocation in the first half of the 21st century

The next demographic crisis in Sub-Saharan Africa

January 14, 2019

INTRODUCTION

The sub-Saharan African population (SSA) continues to grow rapidly. In 2015 it stood at 969 million and at the United Nations[1] it projects it to rise to 2 168 million in 2050, an average annual growth rate of over 2.3% in the year. For its gross domestic product per capita of 3 634 USD in purchasing power parity (PPP) to double in real terms over the period, the rate of economic growth should be, on average, around 4 , 4%. This may be possible. The average growth rate (PPP) between 1980 and 2000 was almost 3.7% and between 2000 and 2015 it was almost 5.5%[2]. Even so, the SSA will not have reached the 2015 level of per capita income in the next poorest region of the world – the emerging and developing Asia – by 2050.

The slow attraction of most of the SSA population due to absolute poverty is not the only challenge the sub-continent faces. This short will consider the increase in population density in the countries of the SSA and its possible consequences.

POPULATION DENSITY

SSA contains 42 countries, excluding island states. Moreover, excluding countries with less than two million inhabitants in 2015, in 2050 it is expected to have population density of over 100 people per square kilometer, using the United Nations' average fertility projection[3]. Four countries are expected to have higher densities than Belgium, India and the Netherlands in 2015, two more for densities higher than Pakistan, Germany and the United Kingdom and seven with densities higher than France, Denmark, Thailand and Indonesia. The 17 countries represented 62.7% of the SSA population in 2015, falling to 61.9% in 2050.

These are surprising projections, given the low level of urbanization in SSA compared to Southeast Asia, northern Europe and Western Europe, and the question arises: how will the sub-continent react?

Four possibilities are considered here.

1. A prior Malthusian control

Notoriously Malthus thought that population growth had a tendency to overcome economic growth, and when he did, he suggested that the next marriage would reduce fertility. Modern contraception has been added as an instrument. The non-coercive way to reduce fertility is to offer contraception to all women who desire it. The 2013 demographic and health survey in Nigeria found that 49% of married women who wanted contraception had no access to it. The corresponding estimate or Kenya in 2014 was 25%.

If fertility declined from the UN average projection to its low projection, population size in 2050 would fall between 9% and 13% in all 18 countries. Even so, the four most densely populated countries – Nigeria, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi – would continue to have densities of more than 400 per square kilometer. The problem is that even if fertility were to drop to a level that would stabilize the population size in the long run, it would result in population growth in the short and medium term, due to a swelling of young women in the distribution of the population. ;age. A large part of the population already increases in the oven.

2. Urbanization

Urbanization takes away land for agriculture and partly accommodates the increase in population density through a more compact settlement. The cost is the pressure that puts on urban services – the urban population of the SSA will be more than three times larger in 2050 than it was in 2015. And it does not completely remove the pressure on rural areas, whose population should increase by over 50 %[4], at a time when climate change is expected to hit Africa severely. In addition, most city dwellers will have to earn a living through production within their families, with limited opportunities for productivity growth. Of the total SSA population, 77% of those in low-income countries and 72% in low-income countries were employed in this way. Rapid economic growth is likely to be concentrated in the enclaves.

3. International migration

From 1850 to 1914, over forty million people left Europe, mostly going to North and South America. Since the average population of Europe during this period was less than 400 million, this implies a cumulative loss equivalent to more than a tenth of the average population[5]. If the rate of emigration of the late nineteenth century was applied to our 18 countries, over 50 million people would emigrate from them for over 35 years and the rate of population growth would drop slightly from 2.29% to 2.12%.

The stock of migrants to other countries from the age of 18 is estimated by the World Bank to 10 318 000 in 2013 and 12 053 000 in 2017[6]. Assuming an annual mortality rate of 10 per 1000 among emigrants, these estimates imply emigration of 537,000 per year between 2013 and 2017. However, the stock of migrants from other countries in the 18th was of 10 302 000 in 2013 and 13 270 000 in 2017, implying the immigration of 845 000 per year between 2013 and 2017. As a whole, the 18 countries experienced a net immigration in those years and, if the trend persists, international migration will increase the pressure of the population rather than diminish it. If the trend were to reverse, where would the emigrants go?

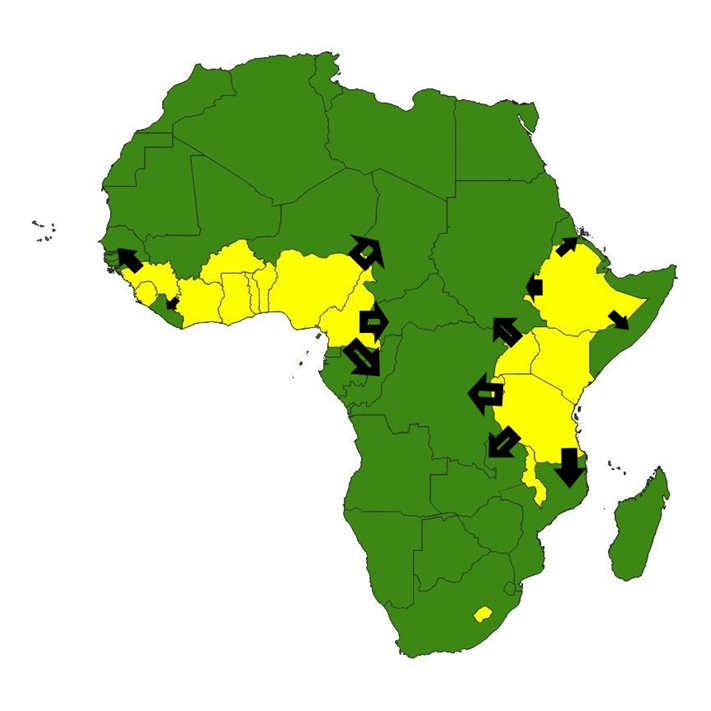

Consider western Africa. It has two characteristics. Ten of the 18 countries are there[7]and the Nigerian population far exceeds that of any other country in the region, projected to 51% of the total in 2050. The movement to the west of Nigeria would encounter other densely populated states, movements towards the north would be limited by the desert. The movement to the east would put pressure on a belt of countries: Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and the Republic of the Congo to Chad and the Central African Republic. Or consider East Africa, with seven densely populated countries. The movements towards the north would imply pressure on South Sudan, Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia, movements towards the east would affect the Democratic Republic of the Congo and emigration to the south would put pressure on Mozambique and Zambia , and probably on Zimbabwe and also South Africa. Of the 12 neighboring states under pressure, four have an average score of at least 9 out of 10[8] on the twelve indicators of state fragility collected by the Fund for Peace, two have average scores between 8 and 9, and five have scores between 7 and 8. All would have great difficulty in resisting large-scale movements.

An informal and unidentified degree of movement between densely populated states and their neighbors is facilitated by a high degree of ethnic splitting (the probability that two randomly chosen people come from different ethnic groups) within densely populated and of their neighbors. As estimated by Alesina[9]12 of the 18 densely populated countries have indices higher than 0.7 and 11 of 12 neighbors are placed in the same range. High levels of fractionation within the country make it likely that the same ethnic group can be found on both sides of a border, allowing migrants to easily get confused with communities in host countries.

Africa – Countries of dense settlements and possible population movements

4. Malthusian positive controls

Malthusian positive controls operate by increasing mortality and include war, disease and famine. If they emerge, famine is the most probable, accompanied by a chronic instability within the stressed countries and beyond their borders.

CONCLUSION

Sub-Saharan Africa will grow by far faster than any region in the world between 2015 and 2050. Under the UN average fertility projection, its population will grow by 124% over the period, compared to 54 % of North Africa, the second fastest growing region. Demographic pressure will be amplified by fragile states and climate change. It would be a miracle if the sub-continent avoided large dislocations in what remains of the first half of the 21st century.

Charles Simkins leads the research of the Helen Suzman Foundation.

Appendix

|

Table 1 – Population density in 2050 |

|

|

Comparison with other countries in 2015 |

|

|

People per square kilometer |

|

|

Austria |

103 |

|

Cameroon |

105 |

|

Lesotho |

106 |

|

Guinea |

109 |

|

France |

117 |

|

Denmark |

128 |

|

Thailand |

134 |

|

Indonesia |

136 |

|

Tanzania |

146 |

|

Ivory Coast |

155 |

|

Burkina Faso |

158 |

|

Kenya |

164 |

|

Ethiopia |

173 |

|

Senegal |

173 |

|

Sierra Leone |

181 |

|

Switzerland |

201 |

|

benin |

212 |

|

Ghana |

215 |

|

Pakistan |

215 |

|

Germany |

229 |

|

UK |

263 |

|

To go |

269 |

|

Viet Nam |

283 |

|

Philippines |

339 |

|

malawi |

352 |

|

Belgium |

370 |

|

India |

398 |

|

Holland |

411 |

|

Nigeria |

445 |

|

Uganda |

448 |

|

Rwanda |

817 |

|

burundi |

926 |

|

bangladesh |

1092 |

[1]World Population Prospects, revision 2017, projection of average fertility

[2]IMF World Economic Outlook, database April 2018

[3]For details, refer to the Appendix, Table 1

[4]The growth span of rural populations in the 17 countries ranges from 8% to 107%.

[5]Richard A Easterlin, influences European overseas emigration before the First World War, Economic development and cultural change, 9 (3), 1961

[6]World Bank, bilateral migration matrix, 2013 and 2018

[7]West Africa has 15 non-island countries

[8]The higher the score, the greater the fragility.

[9] Alberto Alesina et al. splitting up,Journal of Economic Growth 8: 155-94, 2003

[ad_2]

Source link