[ad_1]

IIn five-star hotels, the "Do Not Disturb" sign exerts a strange kind of magic. Privacy is the prerequisite of the rich man, and the staff is trained not to enter a room when the sign hangs from the door handle, anything suspicious can take place inside: a session with a professional escort , a drug deal, an alcoholic spree. It's not their business.

The Michelangelo Hotel, in the exclusive Sandton neighborhood of Johannesburg, looks a little dated these days, but is still one of the most popular meeting places for African government ministers, celebrities and local VIPs – the kind of structure that boasts of its discretion. So when, on January 1, 2014, a young Rwandan accountant named David Batenga introduced himself to Michelangelo and asked the staff to open room 905, the initial reaction was an empty rejection. The guest had hung the Do Not Disturb sign, the receptionist told him.

But Batenga insisted. The room had been booked by his uncle, Patrick Karegeya, former head of Rwanda's external intelligence, on behalf of a young business man visiting Rwanda, Apollo Kiririsi Gafaranga. Batenga was the fixer of his uncle, an occasional and confident driver, so he knew that for a few days, Karegeya was commuting from his home to a gated community at the Michelangelo to drink and eat with Apollo.

In South Africa, Christmas and New Year holidays are a time when schools, shops and government offices close and everyone heads to the beach. Karegeya had moved his family to the United States a few years earlier for concern for their safety, so he was hungry for company. Apollo's visit, a young man with a reputation as a playboy, had given the impression.

But now Karegeya was not answering calls or replying to messages – unusual behavior for a man who had rarely taken off his various smartphones. He had not even called his wife and their three children to wish him a happy new year. He was totally out of character. Batenga had spotted his uncle's car sitting in the parking lot of Michelangelo, he told the hotel receptionist – it was supposed to be on the premises.

Batenga walked back and forth, complained, complained, refused to leave. "I become an asshole, I was literally there all day," he recalled. The hours passed and, in the end, pure madness won. Looking up into the sky, the reception staff finally agreed to call the police to check the room. When they summoned Batenga to the desk, their expressions were grim. The whole atmosphere had changed. "Your guest is dead, sir," one of them announced.

Inside the room 905, where the television was playing at full volume, Karegeya lay on her back on the double bed, her hands on both sides of her face, strips of dried blood around her nose and ears. Normally light-skinned, his complexion had become livid: almost certainly he had been strangled, then covered in a duvet. A cord and a bloody towel had been put in the room's safe. Apollo was gone.

Apollo, Karegeya's family and friends say, had been exterminated in a carefully prepared trap. Karegeya had been a key member of the rebel group that took control of Rwanda after the genocide in 1994 and was appointed as head of external intelligence by Paul Kagame, leader of Rwanda and his longtime friend. But he fell with Kagame and fled the country in 2008, creating an opposition party in exile in South Africa. Apollo made friends with Karegeya and the two became drinking buddies in Johannesburg – the suspicion of Karegeya's mourning family about direct orders from Rwandan intelligence.

Karegeya had every reason to believe that the regime he had done so much to establish was now ready to kill him. He and the other three founders of the exiled opposition party, the Rwanda National Congress (RNC), had been tried in absentia by a military court in Rwanda, which found them guilty of threatening the security of the state and sentenced them to penalties. 24-year-old prisoners. One of the charges – which all four denied – was the responsibility for a series of grenade attacks in the Rwandan capital, Kigali, in 2010.

Several Rwandans in South Africa had warned Karegeya of having received military intelligence calls to Kigali to try to hire contract killers. During the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, one of the other founders of the RNC, General Kayumba Nyamwasa – former head of the Rwandan army staff – was hit in the stomach in a failed attempt to murder while returning from a trip to shopping in Johannesburg with his wife. The South African authorities immediately assigned protection for the two high-profile politicians 24 hours a day.

But Karegeya had sent his bodyguards to pack. An irreverent and irreverent spirit, he found unbearable constant supervision and decided instead to rely on his decades of intelligence experience and a network of contacts to keep a step ahead of his enemies. A basic rule: all meetings must be held in public. Apparently he had broken that rule on New Year's Eve at Michelangelo.

"The only way they could get to my uncle was through a friend," Batenga said. "To get him into that room, he had to be someone he implicitly trusted in. That was always his uncle's weak point, and they knew it: the faith he put in his friends."

The reaction to the murder of Karegeya in Rwanda – especially among his former friends and colleagues – was incredibly cheerful. "When you choose to be a dog, you die like a dog," said the Rwandan Minister of Defense, "and the cleaners will wipe out the trash so that it does not stink." The Prime Minister of the country, Pierre Habumuremyi, said: "Treason the citizens and their country that has made you a man will always bring consequences to you". When Karegeya's daughter expressed her shock during the triumphalist celebration of her father's murder, Rwanda's Foreign Minister Louise Mushikiwabo responded with a tweet: "This man was a self – a declared enemy of Gov and my country, U expect pity? "

When questioned by a Western journalist, Kagame delivered a calculated answer for the benefit of his country's allies and international donors. "Rwanda did not kill this person – and it's a big" no ". Yet he could not resist a following: "But I add this, I really would like Rwanda to do it.

Kagame's message to Rwanda's domestic audience was much more direct. He chose to deliver him, of all places, to a prayer breakfast in Kigali, and was presented with a cautionary finger and a cold smile. "Anyone who betrays the country will pay the price, I assure you," he told a small crowd of dignitaries from the nervous aspect and their wives.

"Anyone still alive who is plotting against Rwanda, whoever he is, will pay the price," Kagame said. "Anyone, it's a matter of time."

This week, five years after the murder of Karegeya, an investigation into what happened to the Michelangelo hotel will finally be opened in a court in Randburg, a northwest suburb of Johannesburg. State attorney Yusuf Baba told magistrate Jeremiah Matopa that he intends to call at least 30 witnesses. The hearings should be extended in February.

The family, friends and mourners of Karegeya hope that the investigation will involve at least arrest warrants for the killers, who are suspected of being a team that escaped to Rwanda. Since none of the suspects are deemed resident in South Africa, this would require official requests for their extradition. The key question, however, is whether the investigation will address the possibility of a political motive and a state collusion in assassination.

"This is the Khashoggi of South Africa," a member of the South African judiciary told me. "And by right, he should receive the same kind of press coverage and raise the same kind of questions." The murder of Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Turkey last October led to worldwide condemnation – but there was only a brief spasm of conscience between allies and business partners of the Saudi monarchy, before the affairs as usual they resumed largely.

The investigation into the murder of Karegeya will raise more thorny ethical issues on the engagement between the western donor nations and the countries emerging from the civil war and famine, many of them African, seek to help. The 1994 Rwandan genocide, in which up to a million Tutsi and Hutus died, was unleashed when President Juvenal Habyarimana's jet was shot down by a missile whose provenance is strongly disputed. With the intensification of fighting, the UN effectively evacuated its peacekeeping force from the country. The Western states have done nothing to prevent the massacres from having treated Rwanda with children's gloves since then, partly due to a sense of guilt often recognized.

After the genocide, Kagame was hailed as one of the leaders of the "renaissance" of Africa, along with Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea and Meles Zenawi of Ethiopia. They were all men who had taken over the barrel of the gun, but were considered visionary social and political reformers, dedicated to raising "the poorest of the poor". In recognition of what many saw as a unique and stimulating collaboration between Western financiers and African beneficiaries, they were nicknamed "donor donor".

The decades that pass have crumbled both Museveni and Isaias, while much of Meles' legacy is dismantled in Ethiopia by a new prime minister. This leaves Kagame – whose country of 13 million people annually receives $ 1.1 billion of aid – as the most important champion of a brand of authoritarian economic development embraced by many aid officials but deplored by human rights activists.

But Kagame's mandate has been haunted by polemics ever since his rebel army, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), took control of the country in July 1994. In the years following the genocide, international criticism focused on brutal events in the eastern forests of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or the Democratic Republic of the Congo), where the RPF chased out those who had committed the genocide, slaughtering hundreds of thousands of Hutu civilians together with them.

More recently, concerns have shifted to the continuing search for the regime of journalists, opposition politicians and social activists, both in Rwanda and in exile. The Karegeya assassination, support human rights groups, was just part of a vast campaign of extra-judicial killings, kidnappings, renditions, beatings, death threats and overseas surveillance with impunity.

"This investigation is making Kagame really nervous," said David Himbara, who once worked as a Kagame economic advisor and now runs a Rwandan pro-democracy group from Canada. "It happens in coincidence with a wave of American concern about human rights in Rwanda and with a very aggressive rhetoric from Kagame, it will remind the world of the Rwanda record on human rights just when it wants the problem to be forgotten."

The public scrutiny of exactly how Patrick Karegeya died will shed light on the abyss between the impressive achievements of Rwanda in alleviating poverty and its record of suppressing political freedom. The process is likely to rekindle a long latent debate over how the global development industry is willing to compromise moral principles at the service of stability.

WI wanted Patrick Karegeya dead? What is striking about this story is the intimacy of the ties that bind its protagonists. Karegeya, Kayumba and Kagame were all Tutsis, part of a Kinyarwanda language community whose territory historically fan of Rwanda, spreading to the Congo, Burundi, Uganda and Tanzania. Traditionally, a Tutsi minority constituted the Rwandan aristocracy of livestock maintenance, while the Hutu servants tended to cultivation. In 1959, an emerging élite hutu who enjoyed the support of colonial Belgium and the Catholic church launched a revolution. The Tutsi royal family was ousted and hundreds of thousands of Tutsis, fleeing from Hutu persecution, settled in neighboring countries.

Kagame, who is of royal blood, grew up in a Ugandan refugee camp dependent on food rations, bitterly aware of his family's fall from grace. Karegeya and Kayumba, on the contrary, both came from well-integrated Ugandan Tutsi families. But as young people during the 70s they all met together in festivals, weddings and market days. Karegeya and Kagame attended the same secondary school in Kampala. In the early 1980s, when Ugandan President Milton Obote began to victimize his community, all three joined the armed resistance led by Museveni, an ambitious left-wing revolutionary.

Their plan was to learn to fight, to go home. Once Museveni won power in Kampala in 1986, these trusted Tutsi cadres established their clandestine army, the RPF, in the Ugandan army. For four years they raised funds and made plans. In October 1990, taking advantage of the absence of Museveni at a UN summit in New York, the RPF invaded Rwanda, taking a huge store of weapons, trucks, boots and uniforms. It was an exodus with biblical tones: the boys were going home.

Karegeya, who worked in Ugandan intelligence, was initially left behind as a liaison, responsible for connecting field commanders with Museveni, but returned to Kigali in late 1994 to manage external intelligence. "Patrick had accumulated a lot of contacts in the world of intelligence," Kayumba told me. "He was very experienced, we all thought he was brilliant."

For Karegeya and his fellow RPF commanders, this was a frantic period when the cops were flying away. Rwanda who took control in 1994 had been devastated by genocide. The rotting bodies were piled up in churches, schools and stadiums, the crops were intact, the buildings had been looted and destroyed by splinters, the civil service and the magistrates were scattered or dead. The former soldiers of the militant Habyarimana and the extremist militiamen were hiding across the borders of the country, plotting to invade.

During these years, Rwanda intervened repeatedly in nearby Zaire, leading a regional alliance that supported the rebels who had shot down the military dictator Mobutu Sese Seko in 1997 (at that point Zaire became the DRC). But Kigali then fell with Mobutu's successor, Laurent Kabila, and continued to support a series of rebel movements operating in the eastern provinces of Kivu. All the while, the government of which Karegeya was a part contributed quietly to the deposits of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, diamonds, gold, tungsten, and timber. The new leaders of Rwanda have been challenged by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International for human rights violations, and repeatedly investigated by the UN for their role in the conflict in the Congo.

African diplomats who have become friends with Karegeya during that era recall a fiery and fiercely intelligent personality who has served more de facto foreign minister than head of intelligence. While part of Karegeya's work was alerting Kagame about potential threats to national security, it also involved the belief of Hutu businessmen returning to Rwanda as investors and persuading the outside world that the RPF was a reliable international partner . He was absolutely loyal to his boss, Kagame, and very good at what he did.

At the height of his power, Karegeya would defend the operations of Rwanda in the military and the secret in an imperious and aggressive manner, telling his friends that the survival of the Tutsi community was in danger. Just as Israel, it would say, a government that knew from experience that no Western power would ever come to its rescue, has retained the right to intervene well beyond its borders. But with the passage of time, he began to have doubts.

For strangers, the RPF looked like a close-knit brotherhood, bound by bonds of sincere friendship, business, marriage, and blood. The wives of Kayumba and Kagame founded and ran a school together, the three couples socialized constantly, their children played one with the other and Kayumba was the godfather of one of Kagame's sons.

But the harmonious facade was misleading. As Kagame emerged as the dominant player, the unhappiness among former close aides grew. The RPF, which had served in words for ethnic reconciliation, had initially been careful to appoint Pasteur Bizimungu, a Hutu, as president, with Kagame (widely recognized as the real decision maker) with the title of Minister of Defense and vice president. In 2000, Kagame canceled that fiction, snatching the presidency at Bizimungu and arresting him when establish a political party. Former members of the disenchanted RPF cite that event as a turning point in their perceptions of Kagame and its ambitions.

Always free of his opinions, Karegeya made his feelings known about what he considered the drift towards totalitarianism. When he attempted, unsuccessfully, to join his family in the United States in 2012, he told the Department of Homeland Security that he had a fight with Kagame on the Rwanda invasion of 1998 by the Rwandan, the arrests and the killings of journalists, the president denies the fundamental rights of citizens and the consistent manipulation of Rwanda's media, business and political processes.

"It was not just me, others were unhappy," he told a French journalist in the last interview he gave. "Some have paid the price, others have decided to remain silent forever.It's a question of choices.If you speak publicly, the consequences are bad.A few have died, others have been imprisoned, others in exile …" He drew analogies with the French Louis XIV. "It became clear that at some point, there was no difference between [Kagame] and the state. As you say in France: "The state is me". And now that he has all the powers, he acts like an absolute monarch. "

After being fired by Kagame, Karegeya entered and exited the detention. He was imprisoned without charge, then held under house arrest, then finally tried and sentenced to 18 months for insubordination. At his release in November 2007, he was warned by a military friend that he would die if he stayed in Kigali. So he escaped.

The high-profile Rwandans who decide to leave the country have developed a strategy. First, persuade a friend to drive to the Ugandan border. So, before being in sight of the customs, stop the car and exit. While your friend crosses the border and undergoes the necessary security checks, cross the river and rejoin the car at an agreed point on the other side.

Three years later, Karegeya was reached in South Africa by Kayumba, the former head of the army, which was very popular among the troops. Kayumba had been sent to India as an ambassador – the kind of presidents' station prey to marginalize potential challengers – but she made the mistake of going back to Rwanda to bury her mother. His military colleagues called him for a dressing, asking Kagame to write an apology for a list of perceived infractions. Instead, Kayumba crossed the night to the border.

Along with two other Rwandan exiles – Gerard Gahima, the former Attorney General, and Theogene Rudasingwa, formerly Secretary General of the RPF – the two men set up the RNC and joined a coalition of political parties. opposition Hutu and Tutsi who hoped to organize a challenge for Kagame. The combination of the RNC intelligence contacts, the popularity with the troops and the diplomatic and legal know-how shook the president. Kigali officials regularly describe its members as "terrorists". In the past, the Kigali government has accused the RNC of joining forces with the democratic forces for the liberation of Rwanda, a group based on the DRC composed of former soldiers and members of the Interahamwe Hutu militia – a calculated accusation for shock traumatized again members of the élite Tutsi, who blame those men for the 1994 massacre of their families and friends. More recently, Kigali has taken his statements in a report prepared by a group of UN experts according to which a militia that receives orders from Kayumba is trained on a plateau in the eastern part of the DRC, an assertion that the RNC he categorically denies.

FThe new countries divide public opinion more dramatically than Rwanda. Where some see a miracle of rebirth, others see a state of oppressive surveillance, a Potemkin village destined for a possible collapse. The articles of foreign journalists visiting Rwanda often seem to follow the same formula: they marvel at the uncontaminated state of the streets, the absence of rubbish – Rwanda was the first African country to ban plastic bags – and the sparklers corrugated tin roofs (rather than confused thatch), and then ooh and aah at the Kigali skyline, its new convention center, its ICT investments, its lean bureaucracy and its embryo welfare scheme. The fact that women represent half of the Rwandan government and 61% of parliamentary seats receive an endorsement, along with statistics – on poverty reduction, school attendance, maternal mortality, bovine vaccination and distribution of bed nets – that make the British Department of International Development beat faster, USAid, Oxfam and Unicef.

Business journalists, usually more difficult to please, enthusiastic about the economy. In a report titled "The Emerging Economy to Watch", Forbes magazine described Rwanda as "a reference model for the continent" last month. He mentioned in particular the Rwanda rankings by Transparency International as the least corrupt country of Africa and the 2nd place on the continent by the World Bank on an index of Ease of doing business.

These results are usually presented by the Rwandan media as a personal work of Kagame, a vision embraced by visitors. Andrew Mitchell, former UK international development secretary, lists Kagame along with Margaret Thatcher as one of the two greatest leaders he has met. "It's a very self-confident regime that has worked wonders over the past 25 years," he told me.

Rwandan newspapers, radio stations and news sites convey a constant stream of speeches and public appearances by the president, in a long podium of praise. In some circles, the skinny president, soberly suited, enjoys the kind of uncritical adulation abroad, once lavished in Aung San Suu Kyi, in Myanmar. A Wikipedia page dedicated to Kagame's honorary degrees and diplomas from Western institutions reaches 26 voices. Tony and Cherie Blair, Bill and Melinda Gates and the Clinton – all of whose bases are heavily invested in Rwanda – are cheeky admirers. When the American philanthropist Howard Buffett appeared with Kagame in a 2016 conference, he announced that the continued investment in Rwanda was conditioned by the fact that the president remained at the helm.

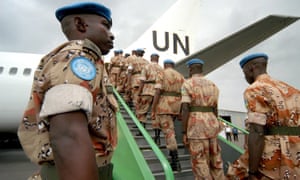

Rwanda also diplomatically hits its weight. The presidency of Kagame for a year of the African Union, which ends this month, has galvanized the continent, while it has launched plans for a free trade area across the continent and contracting member nations on cessation of dependency from western financing. The president's readiness to contribute troops to international peacekeeping operations is particularly good in Washington, which is determined to keep American soldiers on the ground in Africa to a minimum. Rwandan peacekeepers, known for their effectiveness on the ground, are currently deployed in South Sudan and the Central African Republic. Having invited the World Economic Forum to organize an African Davos in Kigali in 2016, he also convinced the Commonwealth to hold its heads of government meeting there in 2020.

These results are a tribute to what a sustained determination and guidance can achieve. But admiration takes a hit as soon as you start examining Rwanda's past about human rights and political freedom.

The post-genocidal constitution drafted in 2003 initially limited Kagame to two mandates in office, but an amendment approved by 98% of voters in 2015 made it theoretically possible for him to remain in office until 2034. At the same time, Kagame joined a certain number of African leaders who are careful not to prepare successors and to avoid setting up institutions that one day could take them into account. The Rwandan elections, in which Kagame regularly wins over 90% of the votes, are barely credible affairs and many of the organizations that regularly monitor the polls in Africa quietly give them a lack.

Given the enthusiasm of Rwanda for advertising gender equality in its political leadership, it is ironic that two women who tried to challenge Kagame in the 2017 presidential election – that Kagame won with 98.8% votes – both were prevented from running. Diane Rwigara, a young Tutsi, was disqualified and later imprisoned for inciting insurrection and falsification. Victoire Ingabire, the most prominent Hutu politician in Rwanda, was already in prison for denial of the genocide. In response to pressure from the United States, both women were released, but too late to compete.

Kigali is a city of well-kept flowerbeds and painted road edges, where it's safe for a young woman to walk home in the evening – not something to be taken lightly on the streets where militia built a family to death at checkpoints. But it is also, according to Kagame's human rights groups and critics, a land of sudden disappearances, mysterious automobile accidents, arbitrary military detention, torture and constant surveillance – where distant relatives or mere associates of those who disapproval of the guilty regime by association.

"Rwanda has done a terrifying job in hiding many of these abuses behind the curtain of economic and social recovery," said Kate Barth, of the human rights organization Freedom Now in an audition at the Congress of States. United in November. "The Rwandan government knows that its abuses will not remain hidden for much longer," he added. "It is time for Rwanda to grant peaceful dissent". Human rights groups report that internal intimidation was accompanied by a shameless campaign to silence Rwandan dissidents abroad – with disrespect for Putin's international borders. A 2014 report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) described 13 cases of former RPF politicians, military figures, secret service agents and journalists who escaped from Rwanda and murdered, kidnapped or attacked in Kenya, Uganda, South Africa or the United Kingdom Kingdom.

"As critics or opponents of the government, victims share a certain profile," reads the report. "Before these attacks, many had been threatened by individuals who were or were close to the Rwandan government." Despite the tendency of government officials to present the history of Rwanda in terms of a besieged Tutsi minority fighting for survival in a Hutu-dominated society, most of those targeted were former members of the Hutu minority. ; RPF both Tutsi.

The hutu politician Seth Sendashonga was killed in his car in Nairobi in 1998, the journalist Charles Ingabire was assassinated in Kampala in 2011 and the former presidential bodyguard Joel Mutabazi was abducted in Kampala in 2013 and taken to Rwanda , where he was tortured and is now serving a life sentence. The HRW report pointed out that these were only the most high profile and best documented cases. "For each of them," said Carina Tertsakian, who worked on the report, "there are scores of little people, not celebrities in Ruanda, che scompare, o viene arrestato e detenuto senza accusa, o assassinato, e nessuno parla mai di loro ".

Il governo ruandese ha sempre negato indignamente la responsabilità di queste cose. Ma non sono solo gli esiliati ruandesi in Sud Africa a essere stati minacciati: le forze di polizia negli Stati Uniti, nel Regno Unito e in Belgio hanno tutti avvertito i dissidenti ruandesi residenti che le loro vite potrebbero essere in pericolo. L'agenzia di frontiera canadese ha descritto un "modello ben documentato di repressione dei critici del Ruanda", mentre la Svezia si è sentita obbligata a mettere un giornalista ruandese in esilio sotto la guardia della polizia ed ha espulso un diplomatico ruandese per spiare i rifugiati ruandesi.

Tre mesi dopo l'omicidio di Karegeya, un altro tentativo fu fatto sulla vita di Kayumba: questa volta la sua casa sicura a Johannesburg fu attaccata da una banda armata. In risposta, un esasperato governo sudafricano ha espulso tre diplomatici ruandesi. Più tardi nel 2014, un giudice sudafricano pronunciò verdetti colpevoli a quattro dei sei uomini processati per il tentato omicidio di Kayumba durante i Mondiali del 2010 – e definì la sparatoria "politicamente motivata". Evitando accuratamente di menzionare Kagame o qualsiasi altro ufficiale ruandese per nome, il giudice ha commentato che i comuni sudafricani erano "stanchi e stanchi delle continue e insensate uccisioni di cittadini stranieri basate su motivi politici".

Le sue parole hanno colpito a casa. "Quel caso era tremendamente importante perché questa era la prima volta che il Ruanda veniva colto in flagrante. Ha mostrato al mondo cosa è il governo ruandese ", ha detto David Himbara dall'esilio in Canada. "La violenza ruandese è finita in un tribunale".

Anche i critici stranieri della situazione dei diritti umani in Ruanda sono stati presi di mira. La giornalista canadese Judi Rever ha trascorso anni a studiare le atrocità commesse dall'RPF per il suo libro In Praise of Blood, pubblicato nel 2018. Mentre stava facendo le sue ricerche, è volata a Bruxelles – dove, con sua sorpresa, la polizia belga, recitando sull'intelligence, le assegnò una squadra di guardie del corpo armate e un'auto blindata. Le è stato detto: "Abbiamo ragione di credere che l'ambasciata ruandese a Bruxelles costituisce una minaccia per la tua sicurezza".

Tegli indagherà a Randburg, che includerà la testimonianza del nipote di Karegeya, David Batenga, e la sua vedova, Leah Karegeya, potrebbe rappresentare una resa dei conti per la reputazione internazionale del Ruanda. Minaccia di diventare un controllo della realtà per i governi occidentali, le agenzie di sviluppo e le fondazioni filantropiche che hanno appoggiato Kagame mentre chiudono un occhio su una massa crescente di indicazioni preoccupanti di violazioni dei diritti umani. Offre la possibilità di riesaminare un paradigma di aiuto che privilegia sempre più l'ordine e la stabilità rispetto alle libertà democratiche.

Funzionari ruandesi professano di non preoccuparsi. "Non c'è nulla di nuovo in queste accuse", ha dichiarato l'alto commissario del Ruanda in Sud Africa, Vincent Karega, in una email rispondendo a domande sul caso. "Sono stati riciclati molte volte in [the] media, anno dopo anno. Rwanda has nothing to do with the death of Patrick Karegeya.” He added that Karegeya and Kayumba had been convicted of terrorism in Rwanda and should be brought to justice: “Whichever way, Rwanda is confident to deal with any threat to the country and its leadership integrity against any detractors’ actions.”

That’s not the way Kagame’s critics see it. When I interviewed General Kayumba last November, the realities of life under a de facto death sentence from Rwanda were apparent. I was driven to the meeting, whose venue I was not told in advance, by a South African bodyguard whose loose cotton shirt barely concealed a gun. I was eventually shown to a dark corner of an anonymous steakhouse off a busy freeway. When he appeared out of the darkness, the general looked in surprisingly good shape for someone who still has a bullet fragment from the 2010 assassination attempt lodged near his spine.

We sat with our backs to a brick wall, under the watchful eyes of his security detail. The continuing risk to the general and his fellow dissidents was recently highlighted by the case of Alex Ruta, a Rwandan intelligence officer seeking asylum in South Africa, who has testified in court that he was sent to Johannesburg in 2014 with orders to eliminate prominent members of the RNC.

“We have a moral obligation not to let this opportunity slip by,” Kayumba said of the inquest. “When Kagame kills in his own country, he gets away with it, there’s silence. If we cannot even have a voice in the place we have run away to, then what is the point of running? We should have just stayed in Kigali and supported the regime.”

For the general, giving evidence at the inquest represents a duty to a friend whose posthumous maligning by former friends and colleagues still cuts to the quick: “We must ensure that justice is delivered to Patrick, who did not deserve to die in this way.”

But the inquest’s outcome could reverberate far beyond South Africa. The principles of international development, insiders say, have changed since the idealistic era that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall, when the industrialised north felt the reconstruction of war-traumatised nations was within its gift, and dreamed of strong civil societies that would spread western values across Africa. In the era of Trump and rising European nativism, the focus has shifted toward backing “reliable” partners in the developing world who promise stability, law and order, and support in the fight against Islamist terrorism.

“There’s been a palpable shift. We’ve gone from the new world order, with its commitment to entrenching human rights and democracy, back to a new version of the cold war,” said Phil Vernon, a veteran British development consultant. “One thing you always hear about Kagame is: ‘He gets stuff done.’ There’s that phrase attributed to Franklin Roosevelt [about Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza García]: ‘He may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.’”

Andrew Mitchell, the former international development secretary, has no time for what he sees as criticisms delivered from “the luxury of 800 years of democracy”, saying: “There a tendency for Rwanda to be judged through the eyes of sophisticated western soi-disant liberals, and that’s the wrong way to view it.” The key question, he said, is: “What is the direction of travel – are they getting better or worse? Alongside extraordinary development progress, there has been, and is, movement in the right direction. This is a very tough, very good regime which makes up its mind on the basis of its own self-confidence.”

Opinion in the international community has splintered in tandem with Kagame’s former inner circle. Many feel that the time when concerns about human rights, or the military’s stifling presence in Rwandan society, would be best raised discreetly behind closed doors has passed. “We need to ask ourselves whether we’re going down the right route, as allies of Rwanda,” Vernon said. “Or whether we should be playing the role of sceptical friend, telling an ally when it’s done something which, in our eyes, is completely wrong – and saying so publicly.”

• Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign up to the long read weekly email here.

[ad_2]

Source link