[ad_1]

Scientists believe the shark developed its rotating jaw to accommodate tooth growth.

Fossils of a prehistoric shark that inhabited the surrounding waters of Morocco have been discovered and based on these remains a team of scientists conducted a study, which suggests that this shark had the terrible ability to rotate the jaw, where a row of sharp teeth it was protruding when its mouth opened to feed.

According to LiveScience, this prehistoric shark called Ferromirum oukherbouchidates lived 370 million years ago. It was a ferocious ocean predator with a lithe and agile body, a short triangular snout with exceptionally large eyes, with eye sockets that took up about 30 percent of the total length of its skull.

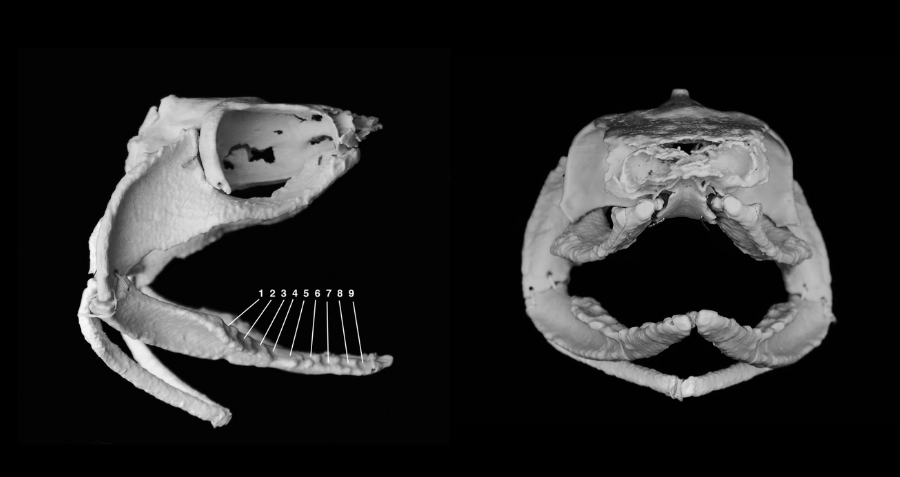

In a study published in the journal Communications Biology, scientists examined the skull and jaw of the prehistoric shark using X-ray computed tomography (CT) and then created a 3D model to perform physical tests.

The biggest difference the researchers found between F. oukherbouchidates and its modern siblings was their unique dental structure. Modern sharks easily lose any worn teeth from their powerful bite and quickly a new tooth is born in the same place.

But the prehistoric shark’s jaws were completely different. Whenever the prehistoric shark lost one of its teeth, a new tooth would sprout in a row inside the jaw, next to the older teeth. When the new tooth was born it didn’t grow upward, but curved inward toward the shark’s tongue, essentially flattening its row of teeth when its mouth was closed.

When the prehistoric shark opened its mouth, the cartilage on the back of the jaw flexed so that the sides of the jaw “folded” down and the newer, sharper teeth rotated upward. This allowed the prehistoric shark to deliver an extraordinarily lethal bite on its prey using as many teeth as possible.

When the shark’s jaw closed, the force of its jaw pushed the seawater and its prey towards its throat while, at the same time, its new sharp teeth rotated inward to trap its prey. This horrible method of feeding is known as suction feeding.

The noticeable movement of the jaw, the scientists wrote, was unlike anything found to date in any living fish. This rotating jaw has disappeared with the evolution of modern shark species with rapid tooth growth.

The discovery offered researchers a key opportunity to better understand the biological functions of the jaw in early chondrichthyes, the class of animals that includes sharks and rays.

The new study may also help scientists understand how this specialized combination of jaw movement and tooth placement was distributed across the shark family tree and uncover how tooth clusters have evolved among modern shark species.

[ad_2]

Source link