[ad_1]

Its mission is to understand the links between a planet’s chemistry and its environment by plotting approximately 1,000 known planets outside our Solar System, providing scientists with a complete picture of what exoplanets are made of, how they formed and how they formed. will evolve.

The Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey, or Ariel as it is best known, has undergone a rigorous review process throughout 2020 and is now slated to launch in 2029.

Thanks to government funding through the UK Space Agency, UK research institutions – including UCL, the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) RAL Space, the Department of Technology and the Technology Center of UK astronomy, Cardiff University and Oxford University – are playing a pivotal role in the mission; providing leadership, bringing vital skills, hardware and software, and shaping their goals.

Once in orbit, Ariel will quickly share her data with the general public, inviting space enthusiasts and budding astronomers to use the data to select targets and characterize stars.

Science Minister Amanda Solloway said:

Thanks to government funding, this ambitious UK-led mission will mark the first large-scale study of planets outside the Solar System and enable our leading space scientists to answer critical questions about their formation and evolution.

It is a testament to the brilliant work of the British space industry, our amazing scientists and researchers led by University College London and RAL Space and our international partners that this mission is “taking off”. I can’t wait to see it progress towards launch in 2029.

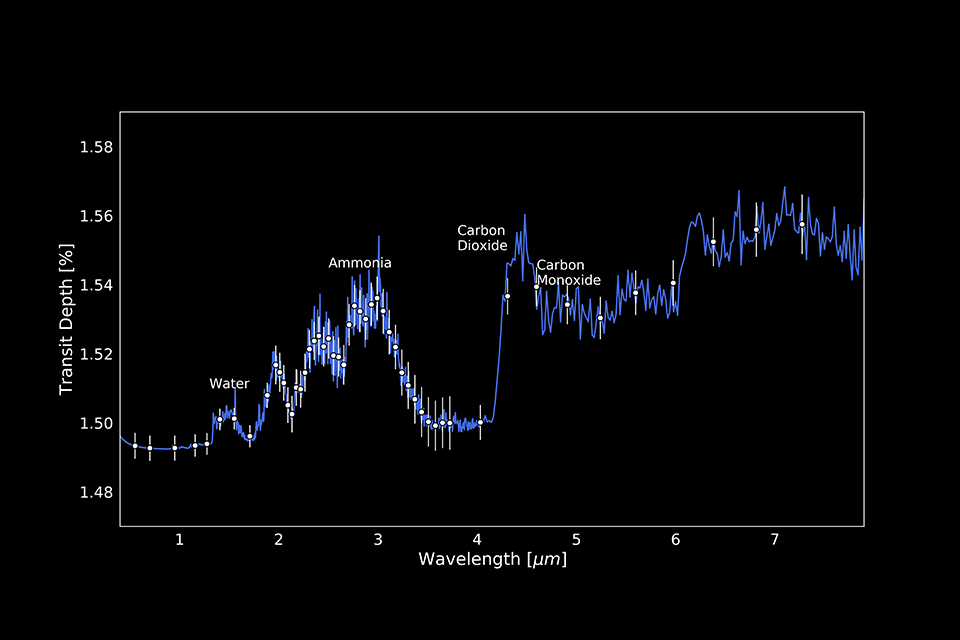

Spectrographs aboard the observatory will study the light filtering through a planet’s atmosphere as it passes – or transits – through the face of its host star, revealing chemical fingerprints of gases enveloping the body.

The instruments will also try to refine estimates of a planet’s temperature by teasing the way its star’s light changes as the body moves behind it, revealing details about a planet’s overall radiation budget.

Ariel will be able to detect the signs of well-known ingredients in the atmosphere of the planets such as water vapor, carbon dioxide and methane. It will also detect more exotic metal compounds to decipher the overall chemical environment of the distant solar system. For a select number of planets, Ariel will also perform a thorough investigation of their cloud systems and study seasonal and daily atmospheric variations.

An example spectrum that Ariel could measure from light passing through an exoplanet’s atmosphere (ESA / STFC RAL Space / UCL / UK Space Agency / ATG Medialab)

Professor Giovanna Tinetti, Principal Investigator for Ariel at University College London, said:

We are the first generation able to study planets around other stars. Ariel will take this unique opportunity and reveal the nature and history of hundreds of different worlds in our galaxy. We can now take the next step in our work to make this mission a reality.

About 4,374 worlds have been confirmed in 3,234 systems since the first discoveries of exoplanets in the early 1990s.

This mission will focus on planets that are unlikely to host life as we know it – from extremely hot to temperate ones, from gaseous to rocky ones that orbit near their parent stars, and a range of masses, particularly those heavier than a few. land masses.

An advantage of studying hot planets is that their atmospheres usually reflect the overall composition of the body, while chemicals from colder planets can condense into clouds high in the atmosphere, thereby hiding the details of the chemistry at altitudes below our view. .

Ariel consortium project manager Paul Eccleston of STFC RAL Space said:

This represents the culmination of a lot of preparatory work by our teams around the world over the past five years to demonstrate the viability and readiness of the payload. Now let’s go full speed ahead to fully develop the project and begin building prototypes of the instrumentation on the spacecraft.

Historically, scientists have tended to focus on the planets that could host life. But the diversity of exoplanet types and systems revealed by the studies so far – and the growing awareness that our system may be atypical – makes understanding the bigger picture that much more important.

.

[ad_2]

Source link