[ad_1]

Imagine you were a fish swimming in the ocean millions of years ago, when a shark lunges at you, opening its mouth wide to bite. The horror of your situation increases when the predator’s lower jaw also stretches down on both sides, so that the newer, sharper teeth that previously lay flat along the side of the jaw now curve upward.

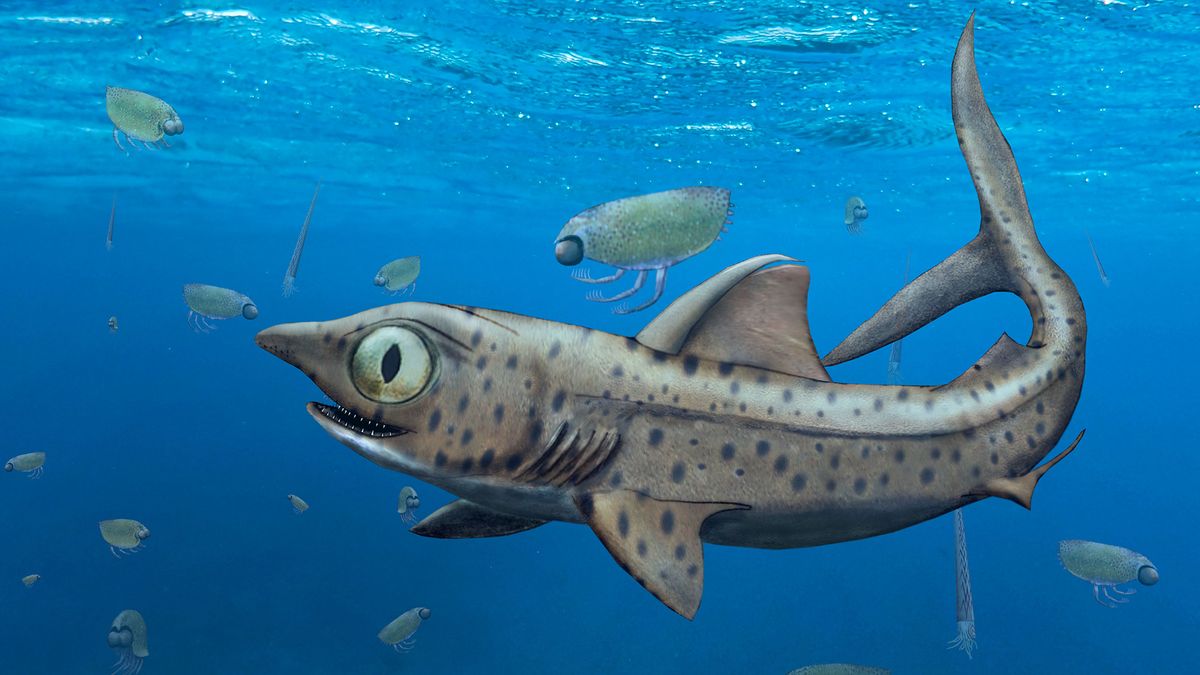

Scientists recently discovered this nightmare trait in a 370-million-year-old shark fossil that once inhabited the waters near what is now Morocco. The previously undescribed species, nicknamed Ferromirum oukherbouchi, had a jaw that rotated inward when the mouth was closed and outward when the mouth was open.

Unlike modern sharks, where worn teeth are constantly replaced by new teeth, this shark has sprouted its newest teeth in a row inside the jaw, alongside the older teeth. As the new teeth grew, they curved towards the shark’s tongue. When the shark opened its mouth, the cartilage in the back of the jaw flexed so that the sides of the jaw “folded” downward and the newer teeth rotated upward, allowing the shark to bite its prey with as many as many teeth as possible, according to a new study.

Related: 8 strange facts about sharks

F. oukherbouchi it had a small, slender body measuring approximately 13 inches (33 centimeters) in length, and the muzzle was triangular and short; his eyes were unusually large, with eye sockets taking up about 30 percent of the total length of the skull, the scientists reported. The shark’s jaw and hyoid arch – the cartilage structures behind the jaw – have been preserved in 3D, offering intriguing clues to the structure and function of the jaw in ancient sharks.

Because the jaw was so well preserved, the researchers were able to scan it with X-ray computed tomography. (CT) and then digitally model it in 3D to conduct mechanical tests. They found that the shark’s jaw was not fused in the center, so it was able to bend outward along this flexible seam when its mouth was open.

“Through this rotation, the younger, larger and sharper teeth, which usually pointed towards the inside of the mouth, were brought upright. This made it easier for the animals to impale their prey,” he said. lead study author Linda Frey, a doctoral candidate at the Institut für Paläontologie und Paläontologisches Museum at the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

When the shark’s jaw closed, seawater rushed into its mouth to push its prey down its throat. At the same time, the locking jaw rotated its teeth inward to immobilize and trap the shark’s meal, Frey said. in a statement. This jaw movement pattern is unlike anything known in any living fish, the scientists wrote in the study.

Previous studies of the jaws in early chondrichthyes – the group that includes sharks, skates and rays – have been hampered by poor fossil preservation. But only a few well-preserved 3D fossils like this one could help paleontologists reconstruct a clearer picture of how ancient shark jaws behaved in 3D, even though most of the extant fossil specimens are incomplete or “flattened,” according to the study. .

Understanding how this specialized combination of jaw movement and tooth placement was distributed across the shark family tree could also explain how the assembly line of ever-growing groups of teeth in modern sharks has evolved, the researchers reported.

The findings were published online November 17 in the journal Communications biology.

Originally published in Live Science.

Source link