[ad_1]

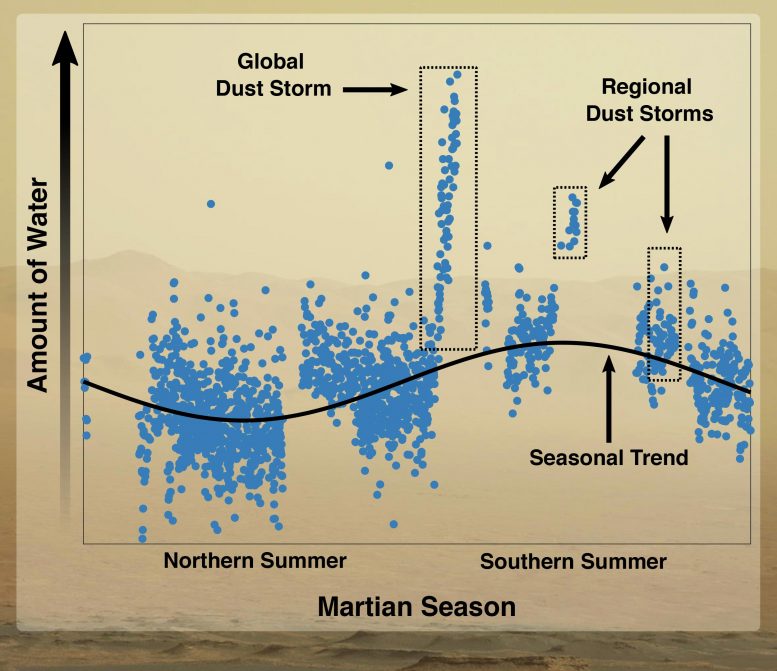

This graph shows how the amount of water in Mars’ atmosphere varies with the season. During global and regional dust storms, which occur during the southern spring and summer, the amount of water increases. Credits: University of Arizona / Shane Stone / NASA Goddard / Dan Gallagher

Scientists using an onboard tool NASA‘S Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN, or MAVEN, spacecraft have found that water vapor near the surface of the Red Planet is carried into the atmosphere higher than anyone expected was possible. There, it is easily destroyed by electrically charged gas particles – or ions – and lost to space.

The researchers said the phenomenon they discovered was one of many that caused Mars to lose the equivalent of a global ocean of water up to hundreds of feet (or hundreds of meters) deep for billions of years. Reporting on their discovery on November 13, 2020, in the magazine Science, the researchers said Mars continues to lose water today as vapor is transported to high altitudes after sublimation from the ice caps during warmer seasons.

“We were all surprised to find water that high in the atmosphere,” said Shane W. Stone, a PhD student in planetary science at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory in Tucson. “The measurements we used could only come from MAVEN as it flies through the atmosphere of Mars, high above the planet’s surface.”

To make their discovery, Stone and his colleagues relied on data from MAVEN’s Neutral Gas and Ion Mass Spectrometer (NGIMS), developed at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. The mass spectrometer inhales the air and separates the ions that make it up based on their mass, which is how scientists identify them.

Stone and his team have been monitoring the abundance of water ions high up on Mars for more than two Martian years. In doing so, they determined that the amount of water vapor near the top of the atmosphere at about 93 miles, or 150 kilometers, above the surface is highest during the summer in the southern hemisphere. During this time, the planet is closer to the Sun, and therefore warmer, and sandstorms are more likely to occur.

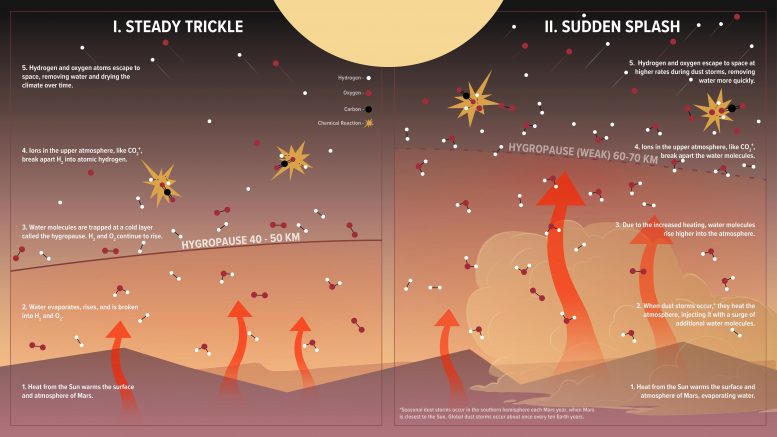

This illustration shows how water is normally lost on Mars compared to regional or global dust storms. Credits: NASA / Goddard / CI Lab / Adriana Manrique Gutierrez / Krystofer Kim

The hot summer temperatures and strong winds associated with dust storms help water vapor reach the higher parts of the atmosphere, where it can be easily broken down into its constituents oxygen and hydrogen. The hydrogen and oxygen then escape into space. Previously, scientists thought that water vapor was trapped near the Martian surface as on Earth.

“Anything that reaches the top of the atmosphere is destroyed, on Mars or on Earth,” Stone said, “because this is the part of the atmosphere that is exposed to the full force of the Sun.”

Researchers measured 20 times more water than usual in two days in June 2018, when a violent global dust storm engulfed Mars (the one that took NASA’s Opportunity rover out of service). Stone and his colleagues estimated that Mars lost as much water in 45 days during this storm as it typically did during a full Martian year, which lasts two Earth years.

“We have shown that dust storms disrupt the water cycle on Mars and push water molecules higher into the atmosphere, where chemical reactions can release their hydrogen atoms, which are then lost to space,” said Paul Mahaffy, director of the Solar System Exploration Division at NASA Goddard and principal investigator of NGIMS.

Other scientists have also found that Martian dust storms can raise water vapor far above the surface. But until now no one had realized that the water would reach the top of the atmosphere. There are abundant ions in this region of the atmosphere that can break up water molecules 10 times faster than they are destroyed at lower levels.

“The particularity of this discovery is that it provides us with a new path that we didn’t think existed for water to escape the Martian environment,” said Mehdi Benna, Goddard’s planetary scientist and co-investigator of MAVEN’s NGIMS instrument. “It will fundamentally change our estimates of how quickly the water escapes today and how quickly it escaped in the past.”

Reference: “The hydrogen leak from Mars is driven by seasonal water transport and sandstorms” by Shane W. Stone, Roger V. Yelle, Mehdi Benna, Daniel Y. Lo, Meredith K. Elrod and Paul R. Mahaffy , 13 November 2020, Science.

DOI: 10.1126 / science.aba5229

This research was funded by the MAVEN mission. MAVEN’s principal investigator is based at the University of Colorado Boulder Laboratory of Atmospheric and Space Physics, and NASA’s Goddard manages the MAVEN project.

[ad_2]

Source link