[ad_1]

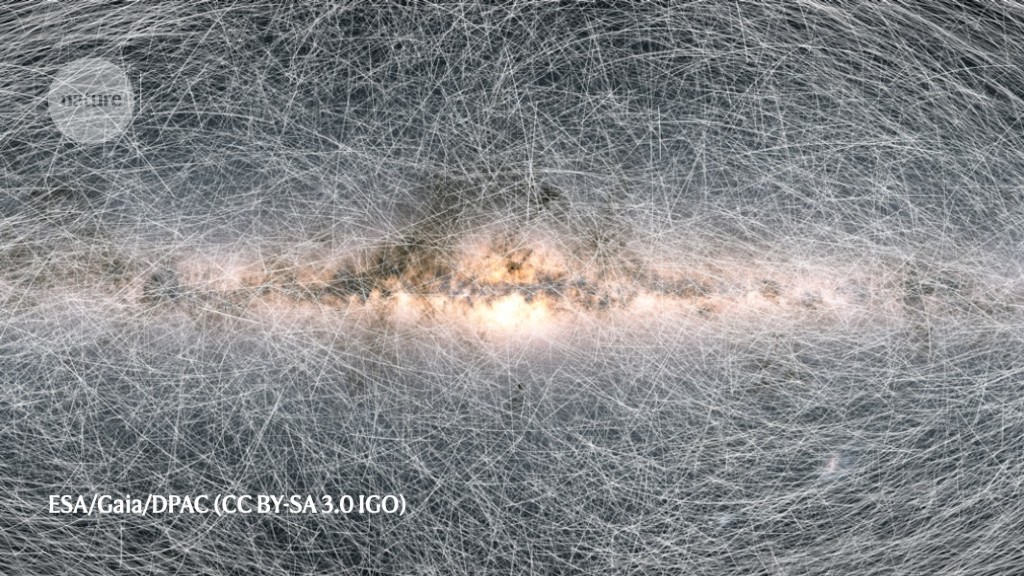

The best available map of the Milky Way just got better. The latest update from the Gaia space observatory, which is monitoring over 1 billion stars in the galaxy, provides not only a static image, but an image of how the stars will move over time. The data will support studies ranging from the origins and evolution of the Galaxy to the location of its dark matter.

“I have yet to see another astronomy project – or any other science – that has such an impact in such a short time frame,” says Amina Helmi, an astronomer at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. “My group is ready to go and is very excited to find out what there is to discover and learn about the Milky Way.” Using data Gaia released in 2018, Helmi and her collaborators studied the movements of a large number of stars to reveal evidence of galactic mergers that occurred billions of years in the past.

Gaia took off in late 2013 and began stargazing in July 2014 from a perch 1.5 million kilometers from Earth. The European Space Agency (ESA) probe continually scans the sky as it slowly rotates on itself, and has now measured the positions of the same stars multiple times. This allows scientists to monitor the almost imperceptible movements of stars in the Galaxy year after year. As Gaia orbits the Sun, its shifting perspective also causes the apparent position of stars to change by small quantities, typically by an angle of millionths of a degree. These offsets can be used to calculate their distance from our Solar System using a technique called parallax.

The kind of information Gaia provides is the daily bread of the camp. Without reliable distance measurement, in particular, it can be difficult to guess the size, age and brightness of a star and then model its structure and evolution.

According to Floor van Leeuwen, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge, UK, the researchers carefully analyzed the two previous mission datasets, released in 2016 and 2018. These are now cited in the literature at a rate of 3,000 times per year. ‘year. So far one website has cataloged 4,324 refereed articles based on Gaia’s data. “You can see the influence of the Gaia data spreading throughout astronomy,” he says.

After the latest update was released on December 3, astronomers began tweeting about the checks they had made on their favorite stars. “It’s like an early Christmas for galactic astronomers,” tweeted Michelle Collins of the University of Surrey in the UK. João Alves of the University of Vienna published plots of the same group of stars to compare the latest Gaia dataset with the previous one, thanking ESA “and the 400 scientists in Europe who make this mission a dream come true”.

Data dump

Gaia’s latest update is made up of 1.3 terabytes – up from 551 gigabytes of the previous one – and is based on about three years of data. The mission has expanded its star catalog by 15% to 1.8 billion, and its measurements have become more accurate. Compared to 2018, Gaia’s distance measurements are 50% better, and those of stellar speeds are 100% better, says van Leeuwen.

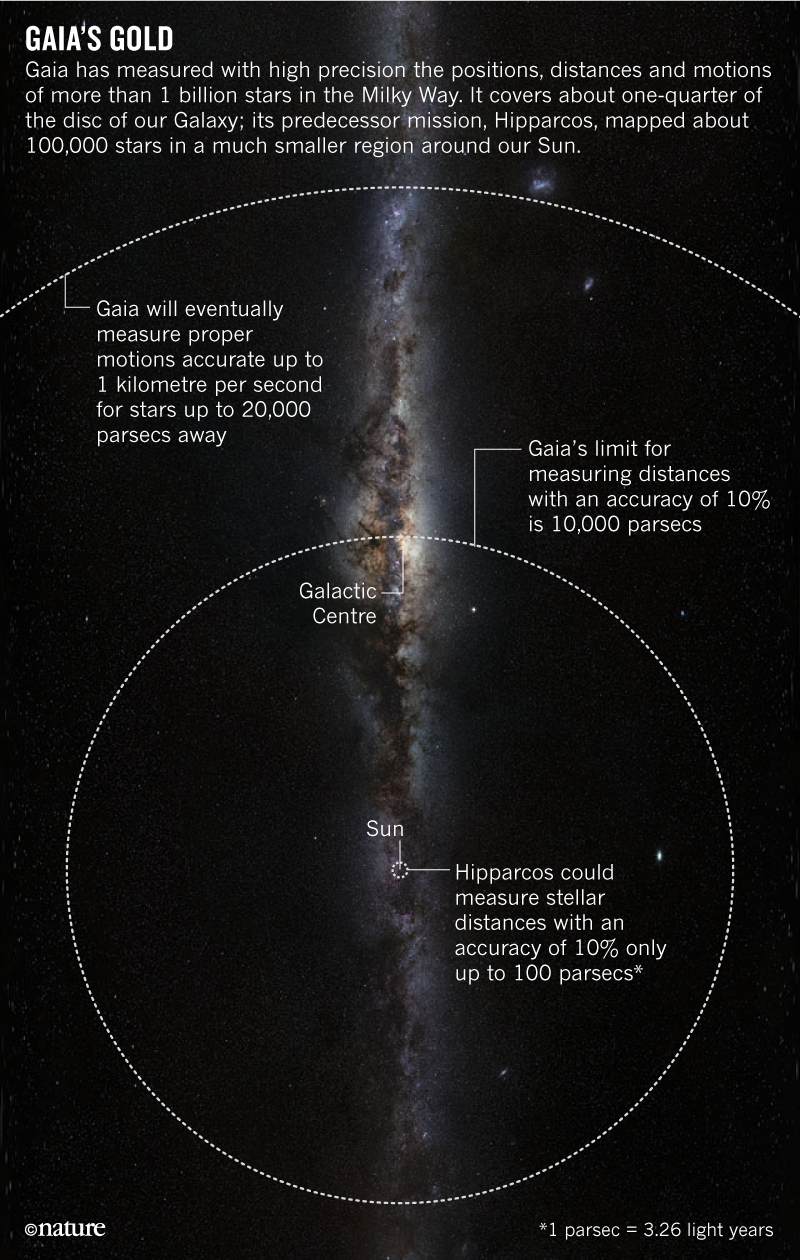

To achieve this improvement, the mission team had to overcome an unexpected problem with the probe. As the spacecraft rotates, sunlight falls on it at varying angles, slightly deforming its shape. This affected his stellar position measurements more than expected. But now the team has learned how to correct this effect at least in part, van Leeuwen says. This means that for stars up to nearly 5,000 parsecs (16,000 light years) in the Solar System, it can measure distances with up to 10% accuracy. Upon completion of the mission, the team plans to achieve this level of accuracy up to distances of 10,000 parsecs, which was their original plan (see “Gaia’s Gold”).

The data release includes a complete census of the Sun’s vicinity: all but the faintest stars within 100 parsecs (326 light years), for a total of over 300,000 objects. Gaia’s detailed measurement of stellar motions also allowed researchers to predict what Earth’s night sky will look like for 1.6 million years to come: As the stars move, all the constellations we currently see will disappear.

In addition to the stars, Gaia also maps quasars, the glowing hearts of other galaxies much further away. Quasars are too distant to show any parallax and appear essentially immobile, making them ideal reference points for tracking the movements of other things, including tectonic plates on Earth. But due to an optical effect of relativity, the sky appears slightly deformed in the direction of the movement of the Solar System in the Milky Way. Now Gaia has measured how that direction changes slightly, as a result of the gravitational pull of the Galaxy: in one year, the Solar System accelerates by 7 millimeters per second.

Denis Erkal, an astronomer at the University of Surrey, UK, quickly used data on the acceleration of the Solar System to rule out the presence of huge clouds of dark matter in near space. The plot tweeted provides only a rough calculation, but already suggests studies that may become feasible as the mission collects more data.

A more complete dataset is expected to be released in 2022 and will include updated stellar spectra. It should also show thousands of stars swinging under the gravitational pull of another object, providing a new tool for discovering thousands of huge exoplanets. Next, the Gaia team plans to produce at least one more significantly improved Galaxy map. The probe has enough fuel to continue operating until 2025.

[ad_2]

Source link