[ad_1]

Astronomers have mapped around one million previously unknown galaxies beyond the Milky Way, in the most detailed survey of the southern sky ever made using radio waves.

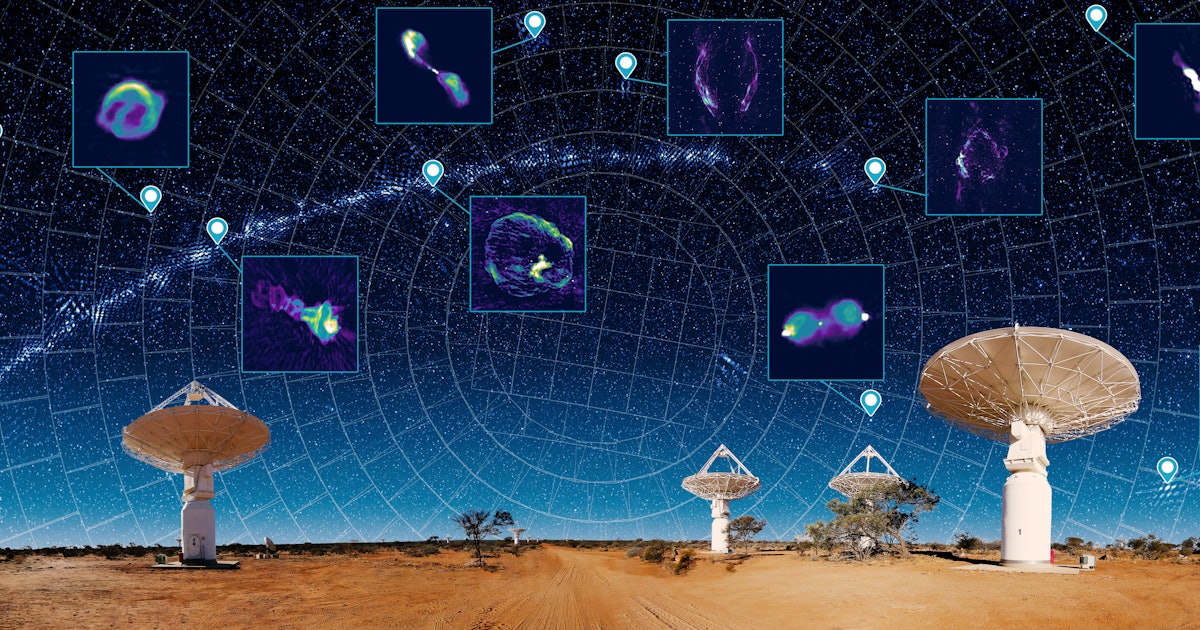

The Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey (or RACS) has firmly positioned CSIRO’s Australian SKA Pathfinder (ASKAP) radio telescope on the international astronomical map.

While previous surveys took years to complete, ASKAP’s RACS survey was conducted in less than two weeks, breaking previous speed records. The data collected produced images five times more sensitive and twice as detailed as previous ones.

What is radio astronomy?

Modern astronomy is a multi-wavelength enterprise. What do we mean by this?

Well, most of the objects in the universe (including humans) emit radiation on a broad spectrum, called the electromagnetic spectrum. This includes both visible and invisible light such as X-rays, ultraviolet light, infrared light and radio waves.

To understand the universe, we need to look at the entire electromagnetic spectrum as each wavelength carries different information.

Radio waves have the longest wavelength of all forms of light. They allow us to study some of the most extreme environments in the universe, from cold clouds of gas to supermassive black holes.

Long wavelengths easily pass through clouds, dust and the atmosphere, but must be received with large antennas. Australia’s wide open (but relatively low-lying) spaces are the perfect place to build large radio telescopes.

We have some of the most spectacular views of the center of the Milky Way from our location in the Southern Hemisphere. Indigenous astronomers have enjoyed this advantage for millennia.

A stellar twist

Radio astronomy is a relatively new field of research, dating back to the 1930s.

The first detailed 30 cm radio map of the southern sky – which includes everything a telescope can see from its position in the southern hemisphere – was the Molonglo Sky Survey of the University of Sydney. Completed in 2006, this survey took nearly a decade to observe 25% of the entire sky and produce final data.

Our team from CSIRO’s Astronomy and Space Science division broke this record by detecting 83% of the sky in just ten days.

With the RACS survey, we produced 903 images, each requiring 15 minutes of exposure time. So we combined them into one map that covers the entire area.

The resulting panorama of the radio sky will look surprisingly familiar to anyone who has looked at the night sky itself. In our photos, however, almost all of the bright spots are entire galaxies, rather than single stars.

Take the virtual tour here.

Astronomers working on the catalog have identified about three million galaxies, far more than the 260,000 galaxies identified during the Molonglo Sky Survey.

Why do we need to map the universe?

We know how important maps are on Earth. They provide fundamental navigation assistance and offer information on the terrain useful for land management.

Similarly, sky maps provide astronomers with an important context for research and statistical power. They can tell us how certain galaxies behave, for example if they exist in groups of companions or if they wander into space alone.

Being able to conduct a full-sky survey in less than two weeks opens up numerous research opportunities.

For example, little is known about how the radio sky changes over time scales from days to months. We can now regularly revisit each of the three million galaxies identified in the RACS catalog to track any differences.

Additionally, some of the biggest unanswered questions in astronomy relate to how galaxies became the elliptical, spiral, or irregular shapes we see. A popular theory suggests that large galaxies grow by merging many smaller galaxies.

But the details of this process are elusive and difficult to reconcile with simulations. Understanding the roughly 13 billion years of cosmic history of our universe requires a telescope that can see over great distances and accurately map everything it finds.

High technology to reach new goals

CSIRO’s RACS survey is an extraordinary advance made possible by huge advances in space technology. The ASKAP radio telescope, which became fully operational in February last year, was designed for speed.

CSIRO engineers have developed innovative radio receivers called “feed phased array” and high-speed digital signal processors specifically for ASKAP. It is these technologies that provide ASKAP’s wide field of view and rapid detection capability.

In the next few years, ASKAP is expected to conduct even more sensitive investigations in different wavelength bands.

Meanwhile, the RACS survey catalog is greatly improving our knowledge of the radio sky. It will continue to be a key resource for researchers around the world.

Full resolution images can be downloaded from the ASKAP data archive.

This article was originally published in Aidan Hotan’s The Conversation at CSIRO. Read the original article here.

Source link