[ad_1]

Poplar trees like these along the Snoqualmie River can thrive on rocky embankments, despite the poor availability of nutrients such as phosphorus in their natural habitat. Microbes help these trees capture and use the nutrients they need for growth. Credit: Sharon Doty / University of Washington

Phosphorus is a necessary nutrient for plant growth. But when applied to plants as part of a chemical fertilizer, phosphorus can react strongly with minerals in the soil, forming complexes with iron, aluminum and calcium. This blocks phosphorus, preventing plants from accessing this crucial nutrient.

To overcome this problem, farmers often apply an excess of chemical fertilizers to agricultural crops, causing phosphorus to accumulate in the soil. The application of these fertilizers, which contain chemicals other than phosphorus alone, also leads to harmful agricultural runoffs that can pollute nearby aquatic ecosystems.

Now a research team led by the University of Washington and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory has shown that microbes taken from trees growing alongside streams fed by pristine mountains in western Washington could make phosphorus trapped in soils more accessible to agricultural crops. The results were published in October in the journal Frontiers in plant science.

Endophytes, which are bacteria or fungi that live inside a plant for at least part of their life cycle, can be considered “probiotics” for plants, said senior author Sharon Doty, a professor at the UW School. of Environmental and Forest Sciences. Doty’s lab has shown in previous studies that microbes can help plants survive and even thrive in nutrient-poor environments and help clean up pollutants.

In this new study, Doty and collaborators found that endophytic microbes isolated from wild plants helped to unblock precious phosphorus from the environment, breaking down the chemical complexes that made phosphorus unavailable to plants.

“We are harnessing a natural plant-microbe partnership,” Doty said. “This can be a tool to advance agriculture because it provides this essential nutrient without harming the environment.”

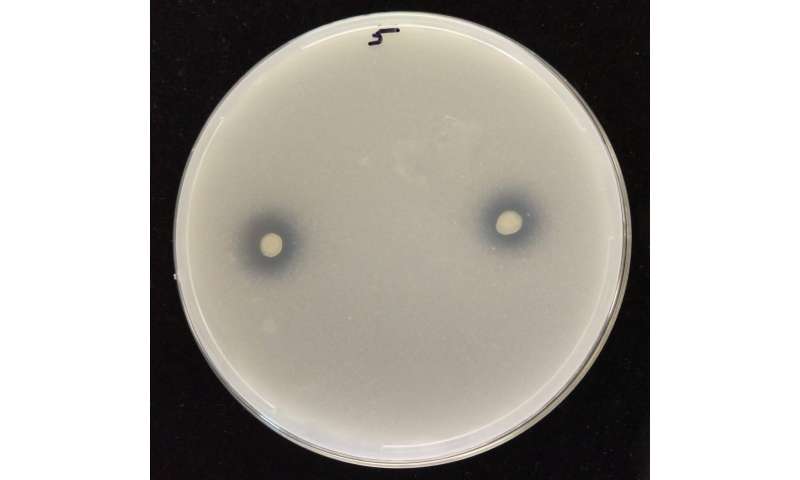

When an endophytic strain dissolves the tricalcium phosphate, a clear halo is produced around the milky white phosphate circles, as seen in this image of the process occurring in an agar medium. Credit: Sharon Doty / University of Washington

Doty’s researcher Andrew Sher and UW researcher Jackson Hall have shown in laboratory experiments that microbes could dissolve phosphate complexes. Poplar plants inoculated with the bacteria in Doty’s lab were sent to collaborator Tamas Varga, a materials scientist at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory’s Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory in Richland, Washington. There the researchers used advanced imaging technologies in their lab and other U.S. Department of Energy national labs to provide clear evidence that phosphorus made available by microbes has entered the plant’s roots.

Imaging also revealed that phosphorus binds to mineral complexes within the plant. Endophytes, which live inside plants, are uniquely positioned to dissolve those complexes, potentially maintaining the supply of this essential nutrient.

While previous work in Doty’s lab has shown that endophytes can supply nitrogen, obtained from the air, to plants, such direct evidence of plants using dissolved phosphorus from endophytes was not previously available.

The bacteria used in these experiments came from wild poplars that grow along the Snoqualmie River in western Washington. In this natural environment, poplars are able to thrive on the rocky banks of rivers, despite the low availability of nutrients such as phosphorus in their natural habitat. Microbes help these trees capture and use the nutrients they need for growth.

These results can be applied to agricultural crops, which are often found, unused, on an abundance of “inherited” phosphorus that has accumulated in the unused soil from years of fertilizer applications. The microbes could be applied in the soil between young cultivated plants, or as a coating on the seeds, helping to unblock the phosphorus held captive and making it available for use by plants to grow. Reducing the use of fertilizers and employing endophytes, such as those studied by Doty and Varga, opens the door to more sustainable food production.

“This is something that can be easily enlarged and used in agriculture,” Doty said.

UW has already licensed the endophyte strains used in this study to Intrinsyx Bio, a California-based company working to commercialize a collection of endophytic microbes. Direct evidence provided by Doty and Varga’s research on endophyte-promoted phosphorus uptake is “changing the game for our crop research,” said John Freeman, scientific director of Intrinsyx Bio.

The grasslands of the Peak District are key to global plant diversity

Tamas Varga et al Phosphorus promoted by endophytes Solubilization of people, Frontiers in plant science (2020). DOI: 10.3389 / fpls.2020.567918

Provided by the University of Washington

Quote: Microbes Help Unlock Phosphorus for Plant Growth (2020, Nov 25) Retrieved Nov 25, 2020 from https://phys.org/news/2020-11-microbe-phosphorus-growth.html

This document is subject to copyright. Aside from any conduct that is correct for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.

[ad_2]

Source link