[ad_1]

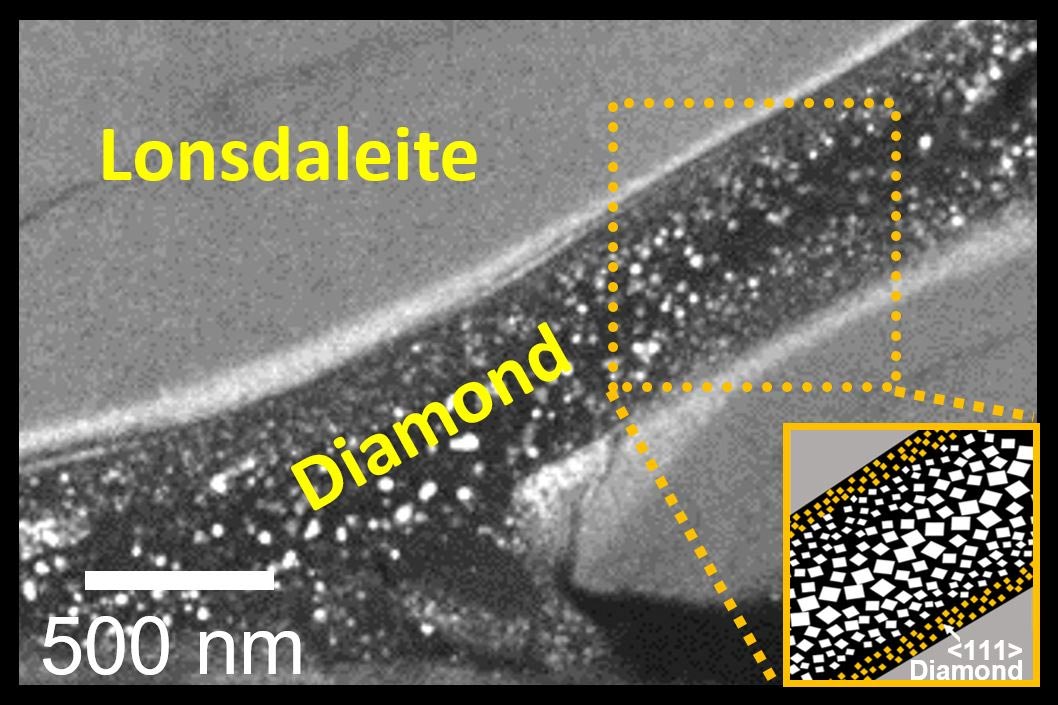

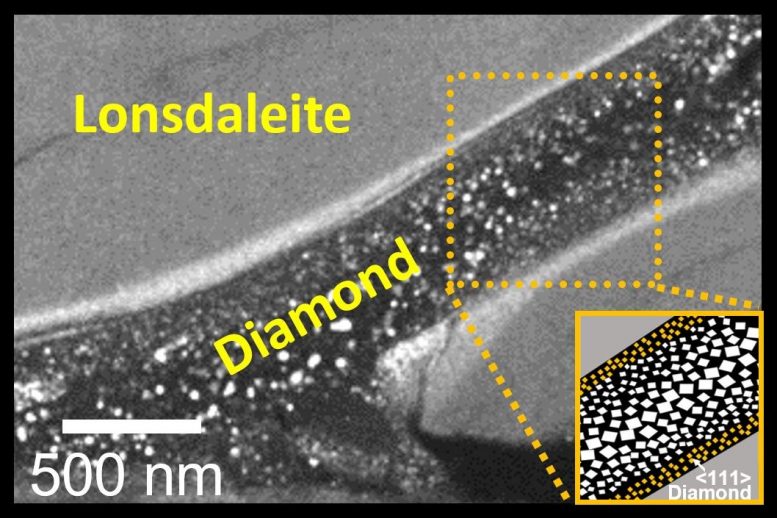

Images from the RMIT team showed that regular diamonds only form in the middle of these Lonsdaleite veins with this new method developed by the interinstitutional team. Credit: RMIT

An international team of scientists has challenged nature to create diamonds in minutes in a laboratory at room temperature, a process that normally takes billions of years, enormous amounts of pressure and extremely high temperatures.

The team, led by The Australian National University (ANU) and RMIT University, have made two types of diamonds: the type found on an engagement ring and another type of diamond called Lonsdaleite, which occurs naturally at the meteorite impact site such as Canyon Diablo in the United States.

One of the lead researchers, ANU’s Professor Jodie Bradby, said their breakthrough shows Superman may have had an ace up his sleeve when he crushed coal into diamond, without using his heat beam.

“Natural diamonds usually form over billions of years, about 150 kilometers deep in the Earth where there are high pressures and temperatures above 1,000 degrees. Centigrade“Said Professor Bradby of the ANU Research School of Physics.

ANU Professor Jodie Bradby holds the diamond anvil in her hand that the team used to create the diamonds in the lab. Credit: Jamie Kidston, ANU

The team, including former ANU doctoral scholar Tom Shiell now at the Carnegie Institution for Science, had previously created Lonsdaleite in the lab only at high temperatures.

This unexpected new discovery shows that both Lonsdaleite and normal diamond can form even at normal room temperatures simply by applying high pressures, equivalent to 640 African elephants on the toe of a dance shoe.

“The turning point in history is the way we apply the pressure. In addition to very high pressures, we also allow carbon to experience something called “shear,” which is like a twisting or sliding force. We believe this allows the carbon atoms to move into position and form Lonsdaleite and normal diamond, ”said Professor Bradby.

Co-lead researcher Professor Dougal McCulloch and his team at RMIT used advanced electron microscopy techniques to capture solid, intact slices from experimental samples to create snapshots of how the two types of diamonds formed.

‘Our images showed that regular diamonds only form in the middle of these Lonsdaleite veins with this new method developed by our interinstitutional team,’ said Professor McCulloch.

PhD student Brenton Cook (left) and Prof Dougal McCulloch with one of the electron microscopes used in the research. Credit: RMIT

“Seeing these little ‘rivers’ of Lonsdaleite and regular diamonds for the first time was just amazing and really helps us understand how they could form.”

Lonsdaleite, named after crystallographer Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, the first woman to be elected as a member of the Royal Society, has a different crystal structure than ordinary diamond. It is expected to be 58% harder.

‘Lonsdaleite has the potential to be used to cut ultra-solid materials at mining sites,’ said Professor Bradby.

“Creating more of this rare but super useful diamond is the long-term goal of this work.”

Ms. Xingshuo Huang is an ANU graduate student who works in Professor Bradby’s laboratory.

“Being able to make two types of diamonds at room temperature was exciting to get to our lab for the first time,” Ms. Huang said.

The team, which involved the University of Sydney and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the United States, published the research results in the journal Small.

Reference: “Investigation of Room Temperature Formation of the Ultra – Hard Nanocarbons Diamond and Lonsdaleite” by Dougal G. McCulloch, Sherman Wong, Thomas B. Shiell, Bianca Haberl, Brenton A. Cook, Xingshuo Huang, Reinhard Boehler, David R. McKenzie and Jodie E. Bradby, November 4, 2020, Small.

DOI: 10.1002 / smll.202004695

[ad_2]

Source link