[ad_1]

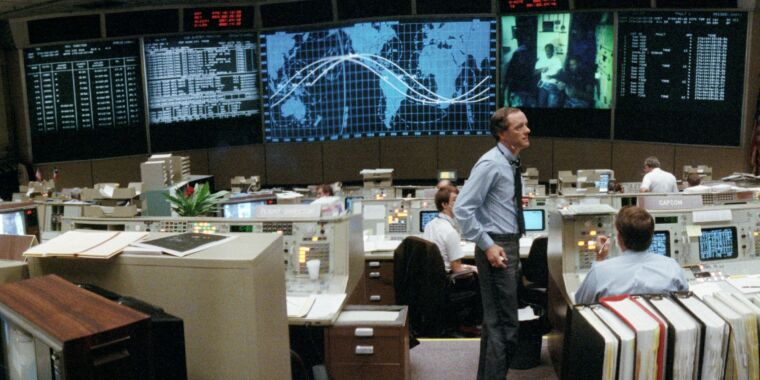

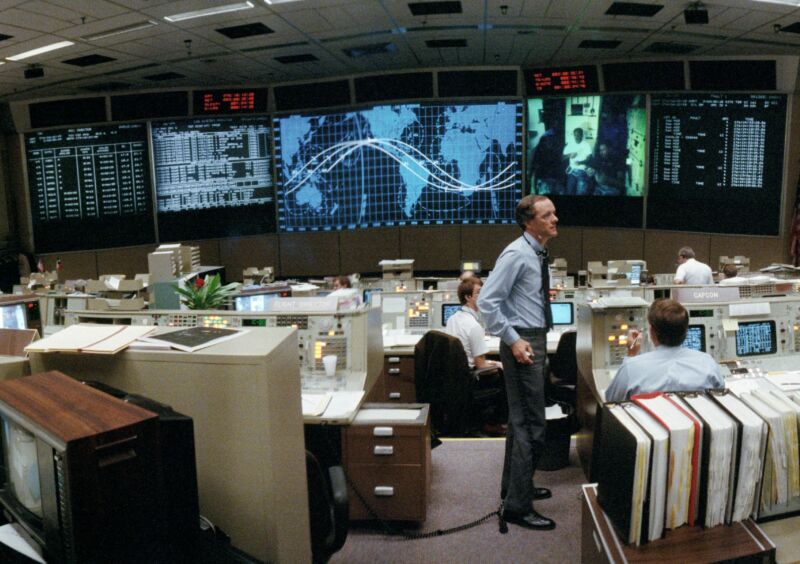

NASA

The call from “The Mountain” to Mission Control in Houston came at almost the worst possible time. It was early Thanksgiving morning in 1991. In space, the crew members aboard the space shuttle Atlantis they were sleeping. Now, suddenly, Chief Flight Director Milt Heflin was faced with a crisis.

Mission Control’s flight dynamics officer informed Heflin that Cheyenne Mountain Air Force Station, which monitored orbital traffic, had called to warn that a dormant Turkish satellite had a potential conjunction with the space shuttle in just 15 minutes. Additionally, this potential debris impact should have occurred in the midst of a crew communications blackout as the spacecraft passed over the southern tip of Africa.

There was no way for Heflin’s engineers to calculate an avoidance maneuver, wake the crew and communicate with them before the blackout period began. Heflin was livid: Why hadn’t the Air Force given more warnings about a potential collision? Typically, they provided approximately 24 hours notice. By God, if that satellite hit Atlantis, they could very well lose astronauts while they slept. The STS-44 crew may never wake up.

An experienced flight director who had started working at the space agency more than two decades earlier during the Apollo program, conducting ocean recovery operations after moon landings, Heflin was largely unperturbed. But now it’s stiffened. “When I think of all my time, I don’t remember ever being so nervous or angry about anything like then,” he told Ars recently.

What Heflin did not know at the time, however, is that he had been hampered by two of his flight controllers during an otherwise boring night shift, during a fairly ordinary shuttle mission to deploy several Air Force payloads. There was no abandoned satellite; the Thanksgiving “turkey” allusion had slipped his mind. But the story didn’t end there.

Practical jokes

At first, NASA was not the buttoned-up space agency it is today. At first, especially during the Mercury program, NASA decision makers moved quickly, often flying from the seats of their pants. There was also more room for practical jokes, even within Mission Control’s inner sanctum.

In his book The birth of NASA, Manfred “Dutch” von Ehrenfried wrote of a legendary practical joke that took place a few weeks before John Glenn’s first orbital flight, in 1962, on an Atlas rocket. Chris Kraft, NASA’s legendary first flight director, led his teams through long days and nights of training, simulations, and discussions about mission rules for this critical flight.

At the time, missions were planned and managed by the Mercury Control Center at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, and there were several scrubs before Glenn’s flight. One night, to break the boredom, Kraft’s key lieutenant Gene Kranz decided to prank his boss the next day when two activities were supposed to run at the same time. Kraft would conduct a mission simulation while Kranz would conduct a launch pad test with the Atlas rocket. While running the mission simulation, Kranz knew that Kraft would be watching the pad’s activities on a television console.

Working with John Hatcher, a video support coordinator for the control center, Kranz replaced an old video of an Atlas launch in Kraft’s feed. Additionally, Kranz and Hatcher programmed it in such a way that the rocket appeared to take off immediately after Kraft pressed the “Firing Command” button as part of its simulation.

Here’s how von Ehrenfried describes what happened next in Florida:

As the simulation progressed, Kraft would ask Kranz how the pad test was doing and Kranz would give him a quick status check with a straight face and head down. When the simulation arrived at takeoff, at the same time Kraft hit the switch, Hatcher played the old Atlas takeoff video on Kraft’s TV console. Kraft’s eyes bulged and his brow furrowed as he stared at the TV. He turns to Kranz and says, “Did you see?” Kranz mutes and says, “See what?” Without a pause, Kraft says, “The damn thing took off!” Hatcher and Kranz tried to keep their faces straight, but couldn’t hold back their laughter. Kraft says, “Who the hell was that?” Then he realized it had been “had” and gave a half laugh. Kranz and Hatcher took off Superman’s cloak and survived!

Source link