[ad_1]

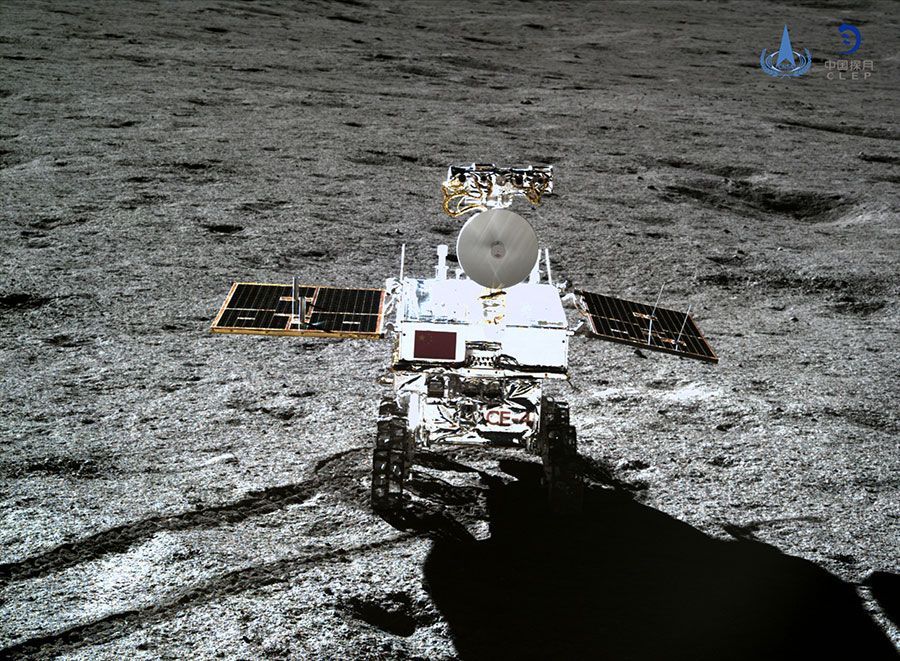

China has been the only country to land on the moon for over 40 years, since the Soviet moon program. His recent Chang’e missions (1-4) proved that China could not only orbit and land on the moon, but also successfully use a rover. On November 24, China’s National Space Administration launched Chang’e 5, the latest in the series.

This mission to collect and return samples is impressive. Recent failed moon landings by a privately funded Israeli mission and India’s Vikram lander show just how challenging these missions still are.

Read more: On the moon and beyond 3: the new space race and how to win

So this is just a case of China using space exploration to show the world that its new scientific and technological capabilities rival those of the West? And if so, what are the consequences?

The mission

Chang’e 5 (named after the Chinese moon goddess) aims to collect samples from Mons Rümker, a 70km wide and 500m high basalt dome in the Oceanus Procellarum Mare region on the left side of the Moon.

The plan is then to return 2 kg of drilled and excavated samples to Earth. If the mission is successful, planetary scientists will be able to test some key theories about the origin of the Moon and the rocky planets of the inner Solar System, which date back to the Apollo era.

The age of a rock body can be estimated from its density of craters. The longer a body exists, the more debris will have bombarded its surface. But it’s not a very accurate measurement. Estimates of the age of Mons Rümker and the surrounding area, derived from the number of impact craters on it, ranged from over 3 billion to 1 billion years.

The absolute age of the returned samples will be determined by radiometric dating. This is a method of dating geological samples by processing the relative proportions of particular radioactive isotopes (elements with more or fewer particles in the atomic nucleus than the standard substance) they contain. This will help us better understand how the density of the crater corresponds to age. And this can then be used to improve age models of surface crater density on the Moon and Mars, Mercury and Venus.

The new space race

Few would argue that the rise of China’s space program – involving satellites, human missions and a space station planned for 2022 – has been swift and successful. But it has competition. The US-led Artemis program has set a goal of returning humans to the moon by 2024, which specifically would be before any Chinese taikonaut landing.

The European Space Agency also has its own plans for the Moon, including the European Large Logistics Lander EL3, which aims to provide a 1.3-ton lander with new science experiments in the late 1920s. However, China’s plans for the moon are becoming more ambitious than Europe’s. A new cohort of 18 Chinese trainee taikonauts recently began their training with long-term goals of crewing their new space station, walking on the moon, and eventually reaching Mars.

The fuel for this rapid growth is research spending in China. The country is nearing its goal of spending 2.5% of its growing GDP on research and development. This is closing the gap to the US, which spent 2.8% of GDP in 2018. The UK currently spends around 1.7% of its GDP on research and development.

China’s capabilities will undoubtedly continue to grow. As a scientist in the West, I wonder how this will affect research in future generations. Will Chinese universities begin to lead space research and influence rankings currently dominated by Western universities? Is this rapid development good, given that the Chinese state is not democratic?

There are reasons for optimism, such as a potential collaboration, at least between Europe and China. The fact that many geochemical models of lunar and planetary formation have their roots in the 380 kg of samples reported by the Apollo missions means that there is worldwide enthusiasm among scientists for sampling a new area of the Moon. Planetary scientists in the West are indeed showing a keen interest in Chang’e 5 and the Chinese lunar program.

One of my earliest memories of space science was the connection of the US-Soviet Union Skylab space station in 1973-74. This was a counterbalance to Cold War-era politics, and it happened despite the absence of democracy in the Soviet Union.

As a university scientist, I believe that having many Chinese students on our campuses over the past decade could help foster future collaboration and change. COVID-19 is hindering it now, so I hope Chang’e 5 is successful and becomes an avenue for future collaboration that could help dissolve the tension.

This article was republished by The conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all Expert Voices issues and debates and become part of the discussion on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Source link