[ad_1]

A variety of clues can suggest to archaeologists a promising spot for excavation. Credit: Gabriel Wrobel, CC BY-ND

National Geographic magazines and Indiana Jones movies might make you imagine archaeologists digging near the Egyptian pyramids, Stonehenge and Machu Picchu. And some of us work in these famous places.

But archaeologists like us want to know how people of the past lived around the planet. We rely on artifacts left behind to help complete that image. We have to dig into places where there is evidence of human activity – those clues from the past aren’t always as obvious as a giant pyramid, though.

Finding this evidence can be as simple as walking through clearly distinguishable ruins – ah, there are some broken vases or carved stones right over there. It can be as complex as using lasers, satellite imagery, and other new geophysical techniques to reveal long-lost structures. The right skills and tools are helping researchers identify traces of the past that would have been overlooked even a few decades ago.

Open eyes, open ears, open minds

The simplest and oldest method of identification is pedestrian investigation – looking for evidence of human activity, both on unstructured walks and when walking in a grid. Unless the evidence is crystal clear – such as those broken vessels – such investigations usually require a trained eye to read the clues.

Archaeologist Josue Ramos of the Belize Institute of Archeology stands next to a recently revealed rock mound in the cleared jungle. Its size and shape indicate that this site is part of an ancient building. Credit: Gabriel Wrobel, CC BY-ND

In Belize, where one of us (Gabe) works, the remains of houses and even great pyramids of temples that were abandoned more than 1,000 years ago are usually overgrown with trees and plants; the exposed sections look like piles of stone.

I took my father to a site where workers had removed the thick foliage so that archaeologists could thoroughly map the site. Another archaeologist and I enthusiastically discussed the visible architectural features: courtyards, terraces, trunks of walls. Eventually, my dad threw his hands up in the air and said “All I see are rocks!”

But our trained eyes recognized that the piles of stones or mounds of earth we saw were suspiciously lined up. Observe the archaeological sites long enough and you will notice them too.

Understanding what you see may also require familiarity with the local geology and flora. And who is more familiar than people living in a region? It pays for archaeologists to make friends with the locals and be very respectful of their knowledge. In my work in Belize, most of the settlements and ritual caves that my students and I work in were initially identified by local hunters who are intimately familiar with the forest and its landmarks.

Once, I was walking through the Belize jungle when a local friend of mine suddenly stopped in what appeared to me to be a random group of trees. He said “This must have been somebody’s farm.” He had seen specific houseplants commonly found in his village gardens. Not being familiar with the local flora, I would never have noticed this subtle difference. Hence, even living plants can be considered part of man-made archaeological sites.

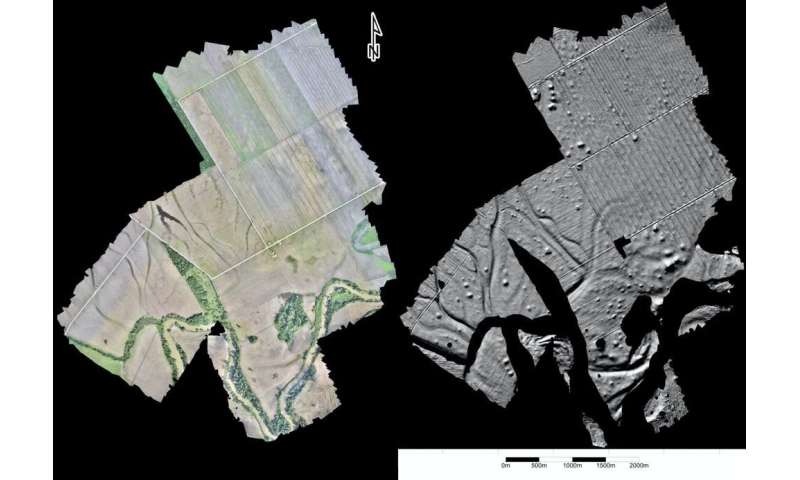

The view of the fields around the Mayan site of Saturday Creek, Belize. The image on the left merged thousands of photographs into a single 3D surface. The image on the right used virtual lighting to highlight small changes in elevation to identify ancient house mounds. Credit: Models created by Mark Willis, used with permission from Eleanor Harrison-Buck, CC BY-ND

High-tech remote sensing

In recent years, archaeologists have begun to use new methods to find archaeological sites that had previously been overlooked. These techniques, widely referred to as remote sensing, allow us to peer through dense forests without clearing them, digitally removing jungle growth and centuries of soil to reveal long-lost structures hidden beneath. High-resolution scans using lasers or 3-D photographs can even detect subtle undulations in ground surfaces that are not visible to the human eye.

For example, LiDAR – light and distance detection – fires pulsed lasers to determine distance based on what it reflects and speed. When used by an airplane, millions of points are collected, resulting in a detailed topographic map of the landscape. Specialists working with this data can remove trees and other objects to digitally expose terrain surfaces.

A recent example at the ancient Mayan city of Tikal, Guatemala, revealed some 61,000 structures in the jungles surrounding the city center. The settlement density came as a shock because, despite extensive pedestrian investigations in the past, even experienced archaeologists have failed to recognize most of these ephemeral remains.

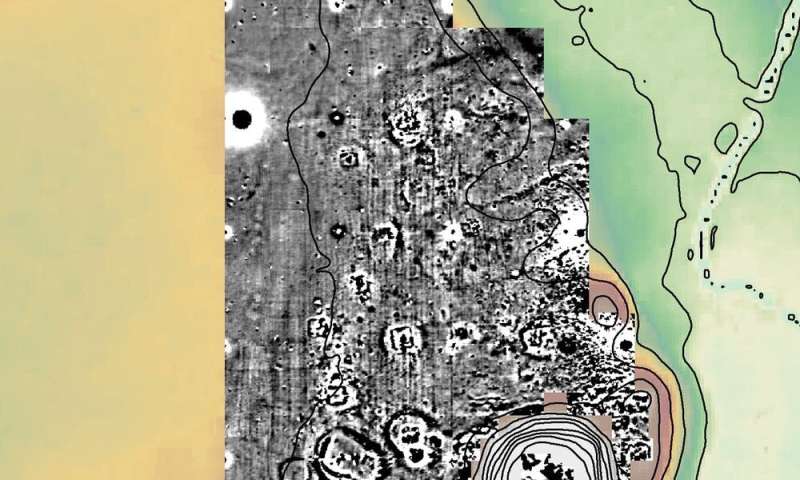

This image features magnetic data from the Hollywood Mounds site, a Mississippi mound center in Tunica County, Miss. Excavations have found that the rectangular shapes are the remains of wattle and daub structures. Credit: Bryan Haley

Archaeologists increasingly find sites by searching for satellite images, including Google Earth. For example, during a recent drought in England, remnants of ancient features began to appear in the landscape and were visible from above.

Remote sensing can also focus on smaller areas. Geophysical techniques are commonly used before digging to scan the ground where researchers know the archaeological remains are buried. These non-destructive methods help identify buried anomalies from surrounding soils by distinguishing their density, magnetic properties or conducting electrical currents.

The shape and alignment of these features can often provide clues as to what they are. For example, the dense walls of a building will be distinct from the surrounding terrain.

-

Tailgating (and associated litter) in the Kibbie Dome parking lot at the University of Idaho in 2011. Credit: Curtis Cawley, Kaitlin Frederickson, Allison Neterer and Wendy Willis., CC BY-ND

-

Future archaeologists will find a lot of plastic – such as these microplastics on a Vietnamese beach – in layers of the Earth dating back to the current era. Credit: Gabriel Wrobel, CC BY-ND

What will the archaeologists of the future find?

As you look around for evidence of human activity in the past, remember that you are actively involved in creating the archaeological sites of the future. Since archeology is the study of any material left by humans, this definition also fits what remains after Nevada’s annual Burning Man festival, for example, or as migrants cross the U.S.-Mexico border.

In fact, there are archaeological sites almost everywhere you look. One of us (Stacey) once studied the trash left over at tailgating parties. My students and I wanted to find out if pupils and students were drinking different types of alcohol. Using archaeological methodologies, we found that alumni celebrated with expensive spirits, such as wine and craft beers, while students drank what they could afford: cheap corporate beers, with Coors Light and Bud Light the most common beers.

We made this archaeological “discovery” by carefully mapping and identifying litter before and during the game. While most have been collected, smaller pieces have undoubtedly found their way into the ground, perhaps to be discovered by a future campus archeology program.

We archaeologists mainly dug in easy-to-find sites. Technology is changing it. Indeed, applications like Google Earth are enabling a new era of citizen science, with researchers sometimes enlisting the help of members of the public to examine data. Through the efforts of archaeologists to engage and educate the public, including incorporating volunteers into the laboratory and fieldwork, holding public lectures and workshops, and creating accessible web resources, we hope to demonstrate that the story of our past is often hidden in nice view.

Sweden: Dog bones found at the Stone Age burial site

Provided by The Conversation

This article was republished by The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Quote: How do archaeologists know where to dig? (2020, December 4) retrieved December 4, 2020 from https://phys.org/news/2020-12-archaeologists.html

This document is subject to copyright. Aside from any conduct that is correct for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.

[ad_2]

Source link