[ad_1]

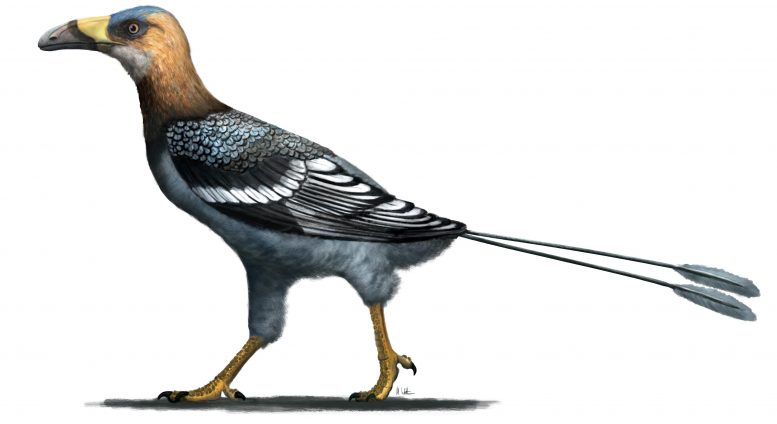

Illustration depicting the first Falcatakely bird among nonavian dinosaurs and other creatures during the Late Cretaceous period in Madagascar. Credit: Mark Witton

A rare fossil from the Cretaceous age opens a new chapter in the history of bird evolution.

- A new bird fossil helps scientists better understand the convergent evolution of complex anatomy and provides new insight into the evolution of face and beak shape in a precursor to modern birds.

- Discovered in Madagascar, the new bird is called Falcatakely, a combination of Latin and Malagasy words inspired by the small size and sickle shape of the beak, the latter representing a completely new face shape in Mesozoic birds.

- State-of-the-art technologies such as microCT scanning, digital reconstruction and rapid 3D printing have enabled scientists to reveal detailed anatomical features, thus contributing to understanding the evolution of birds.

A Cretaceousa bird from Madagascar aged the size of a raven would have made its way through the air brandishing a large blade-like beak, and offers important insight into the evolution of face and beak shape in the Mesozoic predecessors of modern birds. An international team of researchers led by Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine professor Dr. Patrick O’Connor, today announced the discovery in the journal Nature.

Birds have played a vital role in shaping our understanding of biological evolution. Since the mid-19th century, Charles Darwin’s keen observations of the diversity of beak shapes in Galapagos finches influenced his treatise on evolution through natural selection. This fossil bird discovery adds a new twist to the evolution of skulls and beaks in birds and their close relatives, demonstrating that evolution can work through different developmental pathways to achieve similar head shapes in very distant animals.

The new bird gets its name Falcatakely, a combination of Latin and Malagasy words inspired by the small size and the sickle-shaped beak, the latter representing a completely new face shape in Mesozoic birds. The species is known for a single, well-preserved, near-complete skull buried in a muddy debris flow about 68 million years ago. Bird skeletons are rare in the fossil record due to their light and small bones. Bird skulls are an even rarer find. Falcatakely is the second Cretaceous bird species discovered in Madagascar by the team funded by the National Science Foundation.

Artistic reconstruction of the late Cretaceous enantiornithine bird Falcatakely forsterae. Credit: Mark Witton

The delicate specimen remains partially embedded in the rock due to the complex series of lightly constructed bones that make up the skull. Although quite small, with an estimated skull length of only 8.5 cm (~ 3 inches), the exquisite storage reveals many important details. For example, a complex series of grooves on the bones that make up the side of the face indicates that the animal harbored an expansive keratinous cover, or beak, at its waist.

“When the face began to emerge from the rock, we knew it was something very special, if not entirely unique,” notes Patrick O’Connor, professor of anatomy and neuroscience at Ohio University and lead author of the study. “Mesozoic birds with such tall and long faces are completely unknown, with Falcatakely providing a great opportunity to reconsider ideas about the evolution of the head and beak in the lineage leading to modern birds. “

Falcatakely belongs to an extinct group of birds called Enantiornithines, a group known exclusively from the Cretaceous period and predominantly from fossils discovered in Asia. “Enantiornithins represent the first major diversification of early birds, which occupy ecosystems along with their non-avian relatives such as Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus,” says Turner, associate professor of anatomical sciences at Stony Brook University and co-author of the study. “Unlike early birds, such as Archeopteryx, with long tails and primitive features in their skulls, enantiornithins such as Falcatakely it would have looked relatively modern. “

A reconstruction of the life of Falcatakely it might leave the impression that this is a relatively insignificant bird. But it is under the keratinous beak that the evolutionary intrigue lies. O’Connor and his colleagues failed to remove the individual bones of Falcatakely from the rock for study because they are too fragile. Instead, the research team used high-resolution micro-computed tomography (µCT) and extensive digital modeling to virtually dissect individual bones from the rock, with enlarged 3D printing of digital models essential for skull reconstruction and for comparisons with other species.

“A project like this connects disciplines ranging from comparative anatomy, paleontology and the science of engineering and materials. Our partnership with the Ohio University Innovation Center has been a key part of this process, ”noted Joseph Groenke, laboratory coordinator at HCOM / BMS, a study co-author responsible for physical and digital readiness.“ Being able to see each of the bones as a replica of the prototype formed the basis for understanding the sample and also for reconstructing it. “As the research progressed, it was quickly evident that the bones that make up the face in Falcatakely they are organized quite differently from those of any dinosaur, avian or non-avian, despite having a superficially similar face to a number of modern bird groups alive today.

All living birds build the skeleton of their beaks in a very specific way. It consists mainly of a single enlarged bone called the premaxilla. In contrast, most dinosaur-era birds, such as the iconic Archeopteryx, have relatively unspecialized snouts consisting of a small premaxilla and a large jaw. Surprisingly, the researchers found this similar primitive arrangement of bones in Falcatakely but with an overall face shape reminiscent of certain modern birds with a tall, long upper beak and completely different from anything known in the Mesozoic.

“Falcatakely it may generally resemble any number of modern birds with the skin and beak in place, however, it is the underlying skeletal structure of the face that spins what we know about the evolutionary anatomy of birds on its head, “noted O’Connor “There are clearly different evolutionary ways of organizing the facial skeleton that lead to generally similar end goals, or in this case, similar head and beak shape.”

To explore how this type of convergent anatomy evolved, O’Connor hooked up with former OHIO graduate student Dr. Ryan Felice, an expert in skull anatomy in birds and other dinosaurs. “We found that some modern birds such as toucans and hornbills evolved very similar sickle-shaped beaks tens of millions of years later. FalcatakelY. What is so surprising is that these lineages converged on this same basic anatomy despite being very distantly related, “noted Felice, lecturer in human anatomy at University College London (UCL). Dr. Felice completed his PhD in life sciences in 2015, working with O’Connor to examine tail evolution in birds. Felice has since gone on to complete a postdoctoral research position at the Natural History Museum in London, after which he began a position of post at UCL in 2018.

Falcatakely it was recovered from late Cretaceous rocks (70-68 million years ago) in present-day northern Madagascar, in what has been interpreted as a semi-arid and highly seasonal environment. “The discovery of Falcatasmall points out that much of the Earth’s deep history is still shrouded in mystery, “O’Connor added,” particularly from those parts of the planet that have been relatively less explored.

Madagascar has always pushed the boundaries of biological potential. Indeed, Madagascar’s unique biota has intrigued natural historians and scientists from many disciplines, often framed in the context of evolution in isolation on the great island continent.

“The more we learn about the Cretaceous age animals, plants and ecosystems in what is now Madagascar, the more we see that its unique biotic signature extends far back into the past and does not simply reflect the island’s ecosystem in the past. times, “O’Connor said.

“The discovery reported by the doctors. O’Connor and Felice and their collaborators are an extraordinary contribution that opens new perspectives to our understanding of evolution and species diversity, “said Dr. Joseph Shields, vice president of research and creative activity at the University of Ohio. “This work highlights the role of University of Ohio faculty and students in conducting research on sites around the world to advance our understanding of fundamental issues in natural history.”

Reference: “Madagascar’s Late Cretaceous Bird Reveals Unique Beak Development” by Patrick M. O’Connor, Alan H. Turner, Joseph R. Groenke, Ryan N. Felice, Raymond R. Rogers, David W. Krause and Lydia J. Rahantarisoa, November 25, 2020, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038 / s41586-020-2945-x

The study involved researchers from Ohio University, Stony Brook University, University College London, Macalester College, Denver Museum of Nature & Science and Université d’Antananarivo, Madagascar, and was funded by the National Science Foundation. by the National Geographic Society and Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine / Ohio University.

[ad_2]

Source link