[ad_1]

Imagine Antarctica today and what comes to your mind? Big ice floes floating in the Southern Ocean? Perhaps a remote outpost populated with scientists from all over the world? Or maybe colonies of penguins walking through vast expanses of snow?

Fossils from Seymour Island, just off the Antarctic Peninsula, are painting a very different picture of what Antarctica looked like between 40 and 50 million years ago, a time when the ecosystem was richer and more diverse. Fossils of frogs and plants such as ferns and conifers indicate that Seymour Island was much warmer and less icy, while fossil remains of marsupials and distant relatives of armadillos and anteaters suggest earlier connections between Antarctica and other continents in the southern hemisphere.

There were also birds. Penguins were present then, as they are now, but fossil relatives of ducks, hawks and albatrosses have also been found in Antarctica. My colleagues and I recently published an article that reveals new information about the fossil group that would have made all the other birds on Seymour Island pale: the pelagornites, or “bony-toothed” birds.

Giants of the sky

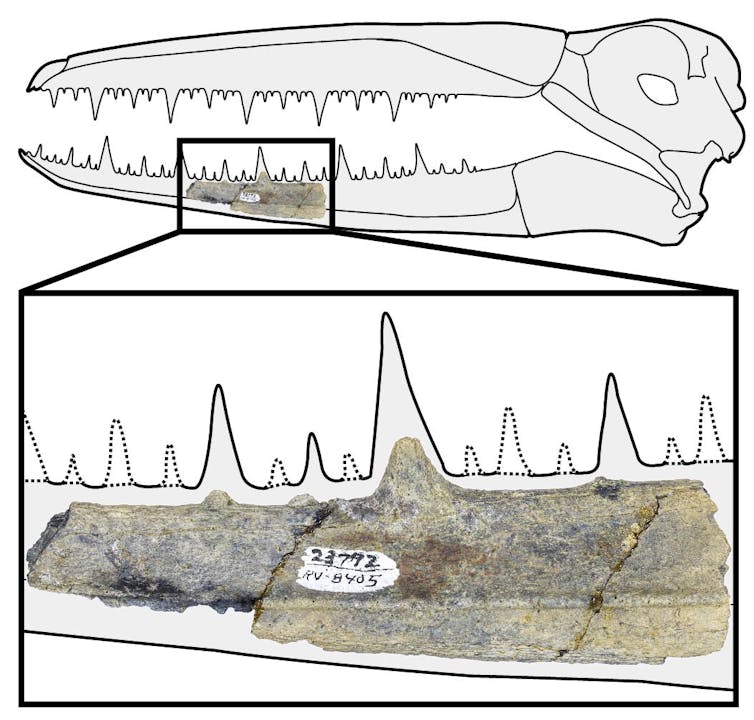

As the name suggests, these ancient birds had sharp bony points protruding from their saw-like jaws. Similar to teeth, these spikes would help them catch squid or fish. We also studied another notable feature of pelagornites: their imposing size.

The largest living flying bird today is the wandering albatross, which has a wingspan reaching 11 and a half feet. The Antarctic pelagornitid fossils we studied have a wingspan nearly double that – about 21 feet in diameter. If you’ve flipped a two-story building on its side, that’s about 20 feet.

In the history of the Earth, very few groups of vertebrates have achieved motorized flight and only two have reached truly giant sizes: birds and a group of reptiles called pterosaurs.

Aneta Leszkiewicz / Wikimedia

Pterosaurs ruled the skies during the Mesozoic era (252 million to 66 million years ago), the same period in which dinosaurs roamed the planet, and reached dimensions that are hard to believe. Quetzalcoatlus was 16 feet tall and had a colossal wingspan of 33 feet.

Birds have their chance

Birds originated while dinosaurs and pterosaurs still roamed the planet. But when an asteroid hit the Yucatan Peninsula 66 million years ago, both dinosaurs and pterosaurs died. Some selected birds survived, however. These survivors have diversified into the thousands of bird species living today. Pelagornithids evolved in the period shortly after the extinction of dinosaurs and pterosaurs, when competition for food diminished.

The earliest remains of pelagornites, recovered from 62-million-year-old sediments in New Zealand, were about the size of modern gulls. The first giant pelagornites, the ones in our study, took off over Antarctica about 10 million years later, in a period called the Eocene Epoch (56 million to 33.9 million years ago). In addition to these specimens, fossil remains of other pelagornites have been found on every continent.

Pelagornithids lasted for about 60 million years before becoming extinct just before the Pleistocene epoch (2.5 million to 11,700 years ago). No one knows exactly why, though, because few fossil records have been recovered from the period to the end of their reign. Some paleontologists cite climate change as a possible factor.

Putting it together

The fossils we studied are whole bone fragments collected by paleontologists from the University of California at Riverside in the 1980s. In 2003, the specimens were moved to Berkeley, where they now reside at the University of California Museum of Paleontology.

There isn’t enough material from Antarctica to reconstruct an entire skeleton, but by comparing the fossil fragments with similar elements from more complete individuals, we were able to assess their size.

Peter Kloess, CC BY-NC-SA

We estimate that the pelagornithid’s skull would have been about 2 feet long. A fragment of a bird’s lower jaw retains some of the “pseudotes” which would each have measured up to an inch in height. The spacing of those “teeth” and other measurements of the jaw show that this fragment came from an individual as large, if not larger, than the largest known pelagornites.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]Further evidence of the size of these Antarctic birds comes from a second pelagornite fossil, from a different location on Seymour Island. A section of a foot bone, called the metatarsal tarsus, is the largest known specimen for the entire extinct group.

These pelagornitid fossil finds underscore the importance of natural history collections. Successful field expeditions result in a large amount of material reported in a museum or repository, but the time it takes to prepare, study, and publish on the fossils means these institutions typically contain far more specimens than they can show. . Important discoveries can be made by collecting specimens on expeditions to remote locations, no doubt. But equally important discoveries can be made simply by working out the backlog of specimens already available.

Source link