[ad_1]

After the Leonid meteors in 2020.

We witnessed an amazing astronomical spectacle in the early morning skies over the Kuwait desert in November 1998. That year, the Leonid meteors performed in a spectacular sight, surpassing about 1,000 meteors per hour near dawn. In most years, however, Leo groans with a few measly meteors per hour, but once every 33 years or so, mighty Leonids can roar with an incredible spectacle that reaches storm-level proportions.

Prospects for Leonids 2020

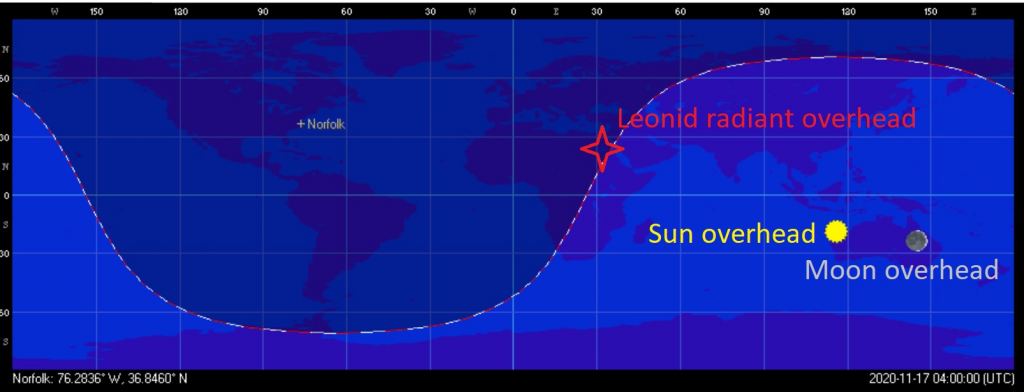

Unfortunately, 2020 shouldn’t be such a year, but it’s always worth keeping an eye on during the wee hours of mid-November. The 2020 peak for Leonids is expected to arrive on Tuesday, November 17th, around 4am (UT) or 11pm EST (16th). The Moon is a crescent crescent just two days after the New at this point, ideal for observing meteors. This also favors the longitude of Europe and Africa at dawn, another advantage. The zenith hourly frequency (ZHR) of 2020 is projected to average 15-20 meteors per hour.

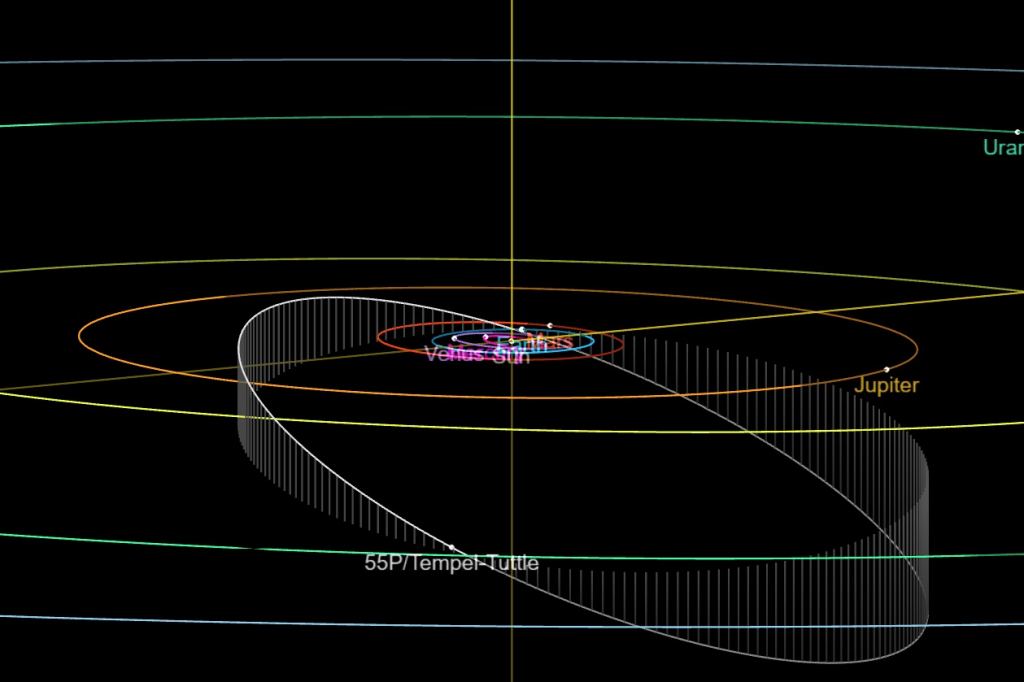

The source of the Leonid meteors is the periodic comet 55P / Tempel-Tuttle, which is on a 33-year orbit around the Sun. The next major peak for the Leonids is expected in the early 2030s around 2032-33, although the circumstances this time may turn out to be less than favorable. It is worth noting that in the late 1990s we saw rates of increase over the course of several years up to 1998, so what we see from the Leonids over the next decade could be indicative of what we might expect, in 2032.

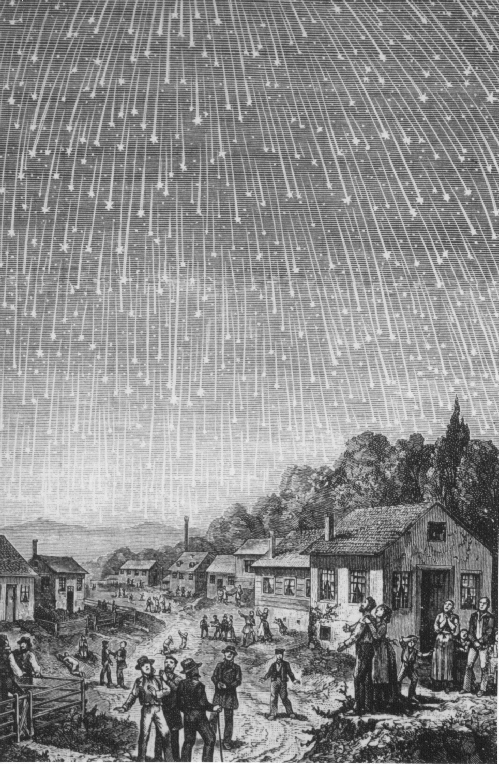

Leonids are one of the most famous producers of meteor storms. On the morning of November 13, 1833, residents of the east coast of the United States woke up to a truly terrifying sight, as the sky seemed to be awash with meteors, which fell like rain. Keep in mind, none really He knew which meteors were actually up to the end of 19th century, or how they related to dust trails drawn by comets. Indeed, the Leonids of 1833 are cited as contributing to many of the 1830s religious fundamentalist revivals in the United States … they were that influential.

Will the Leonids “increase” in the next decade? Keep in mind that the zenithal hourly rate (ZHR) indicated for a given shower is the number you would see under optimal conditions, under a dark, moonless sky with the radian directly overhead … most of us will see a lot less. Many novice observers get excited about the hype that leads to a meteor shower, only to be frustrated by the reality of seeing little or no meteor under light-polluted skies. Be patient and search for a good dark sky site for the best results. Tracing a meteor trail to the “Scythe of the Lion” asterism identifies its membership in Leonides … otherwise, the meteor could be a sporadic background or a member of another shower. In November the Taurids are also active and the December Geminids are also preparing. For best results, observe early in the morning when the Earth encounters the stream of Leonid meteorites head-on.

In recent years, the Leonids have produced an observed peak of 29 (2019), 24 (2018) and 20 (2017) meteors per hour.

Observing a meteor shower is as simple as wrapping up, lying down, watching and waiting. We prefer to look about 45 degrees from one side of the radian for a rain to see the meteors in profile, although honestly they can appear anywhere in the sky. If you are observing with a friend, be sure to look in opposite directions, to double the coverage of the sky. Also, be sure to keep a set of binoculars on hand, as a bright fireball can often leave a lingering smoke train that can remain visible for more than a minute or so.

You can also “feel” the meteors or, more precisely, the ionized reflection crackling in their wake along the empty areas of the FM radio dial. A similar phenomenon is heard along the FM band during an intense thunderstorm. Very occasionally, radio reflections from passing a meteor might even briefly focus on a distant radio station.

But you really can feel meteors? This is a true and persistent phenomenon reported over the years by observers … as a child, I remember hearing a distinct “hiss” that accompanied a brilliant Perseid. Now, meteors are just specks of dust that burn high in the atmosphere, far from the ground and unable to convey sound to the viewer … also, unlike the thunder you hear several seconds after seeing a flash, the effect it seems to be instantaneous. The culprit appears to be what is known as electrophonic sound, an induction of local current created by nearby telephone wires, aluminum siding, and even damp, damp grass surrounding the observer as a meteor passes by.

Meteor imaging is a simple thing too – a tripod-mounted DSLR camera with a wide-angle lens covering a good swath of sky will do the trick. Use the manual “bulb” setting to take a series of exposures of 1-3 minutes and see what comes out. Make sure you take a series of test exposures first, to get the right balance of shutter speed / f / ratio and ISO exposure against local sky conditions. Be sure to carefully examine the shots afterwards … almost all of the meteors we captured with the camera were lost when observing with the naked eye. I like to use a remote intervalometer to automate the process by setting the camera to record a 3-minute series of exposures, leaving me free to sit and watch the show. Also, keep an additional set of camera batteries on hand, preferably in a warm pocket; Long exposures and cold November temperatures can drain camera batteries quickly.

Finally, don’t forget to keep a tally of the number of meteorites you see and to report your observations to the International Meteorological Organization. Amateur radio and visual observations of meteor showers all contribute to our efforts to understand how particular meteor showers evolve and may even discover new meteor streams.

Sure, the sky won’t come ablaze with a Leonid meteor storm in 2020, but it’s always worth watching for the wandering scythe streaks this next week and marvel at what it can be.

Main image: A full-sky capture of a 2011 Leonid. Credit: NASA / MSFC

Source link