[ad_1]

When the first humans began to colonize all regions of the world, many species became extinct. Some have been directly hunted to extinction, others have seen their habitats destroyed, and still others have been wiped out by the introduction of non-native predators such as mice.

One consequence of human-induced extinctions is the distortion of biological models. Studying how evolution works is more challenging if humans have caused the extinction of many species, because the diversity we see today may not be representative of how evolution worked to the point where we entered the scene.

We know that evolution can sometimes take strange paths. For example, while birds are recognized masters of flight, some have nevertheless abandoned this ability to live on land. Bird species often evolve without flying in predator-free environments, because flight is a luxury that is unnecessary when there are no enemies to escape from.

The small bird known as the “Inaccessible Island rail” is one example. As the name suggests, its island is difficult to access and, with no predators living there, the railway can run safely.

Brian Gatwicke, CC BY-SA

Today there are 60 flightless bird species, in 12 bird families – although most are penguins, rails or ostriches and their relatives – and many are threatened with extinction. However, our recent work, now published in Science Advances, found that the evolution towards flightlessness was far more common than these 60 species would suggest, once we took into account the bird species that occurred. they are extinct after man arrives in an area.

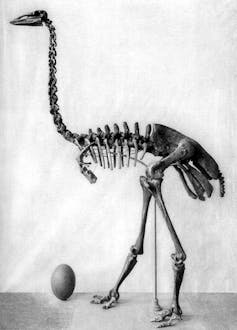

We extracted historical records from archaeological finds to compile a list of 581 probably man-made bird extinctions. Of these species, 166 could be considered flightless (or at best just weak fliers), accounting for 29% of extinct bird species. Examples include: the iconic dodo, a flightless pigeon from Mauritius; the moa-nalos, a species of flightless goose from Hawaii; and the elephant birds, giants of Madagascar which are probably the largest birds that man has ever encountered.

Monnier / wiki, CC BY-SA

The archaeological record therefore increases the list of known flightless birds from 60 to 226, considering both living and extinct species. This shows that the evolution of flightlessness in birds was actually a widespread phenomenon, occurring in at least 40 bird orders and independently evolving at least 150 times.

The major evolutionary transition to flightlessness occurred at four times the speed that would appear to be based solely on living species, suggesting that the evolutionary path from heaven to earth in birds was not as rare as we previously thought. There were flightless ibises, owls, woodpeckers, hoopoes and finches – all sadly now gone.

Our results also show how selective anthropogenic extinctions can be. Many bird species evolved in response to the absence of mammals, so they were particularly vulnerable to humans who came to their islands and carried mammals such as mice with them. In addition to flying, these birds also lost their fear of such predators.

rook76 / shutterstock

The extinction of flightless birds has also led, in some cases, to the disappearance of important ecological functions that are unlikely to be replaced by the remaining species. For example, New Zealand moas likely have taken on the ecological role of mammalian herbivores, grazing on trees and shrubs as do deer or goats native to other continents.

New Zealand plants are thought to have developed new strategies to avoid being eaten by these birds. The remaining flightless bird species represent a fraction of a once larger group, with significant ecological importance to key ecosystem functions including seed dispersal, pollination and plant consumption.

Our findings remind us that what we see in nature today may be very different from what existed before any human impact. It shows us that anthropogenic effects can also hide the frequency of major evolutionary transitions in life forms, distorting the study of evolutionary models.

Humans have removed small pieces from the puzzle that scientists are trying to solve. By finding some of these pieces, we can show that the inability to fly was not as rare as we thought and that to study the natural world, we must take into account that we have profoundly transformed the diversity we want to study. Taking into account not only what we see today, but also what was there before human impact, is the only way to fully understand how nature works.

Source link