[ad_1]

The recently discovered skull of an ancient human relative reveals that the species has undergone dramatic changes over a short period of time, a phenomenon known as microevolution, a new study finds.

Previously, the males of Paranthropus robustus, an extinct australopithecus species (relatives of Lucy), they were thought to be substantially larger than females. This dichotomy is well known among some modern primates, including gorilla, orangutans is baboons. However, a new fossil unearthed in South Africa indicates that sex-attributed differences are actually due to microevolution, as the species evolved rapidly during a turbulent period of local climate change about 2 million years ago.

“Proving that Paranthropus robustus is not particularly sexually dimorphic removes much of the urge to assume they lived in gorilla-like social structures, with large dominant males living in a group of smaller females, “study lead researcher Jesse Martin, a PhD student at the Department of Archeology at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, he said in a statement.

Related: Photo: Ancient human relative found in the Philippines

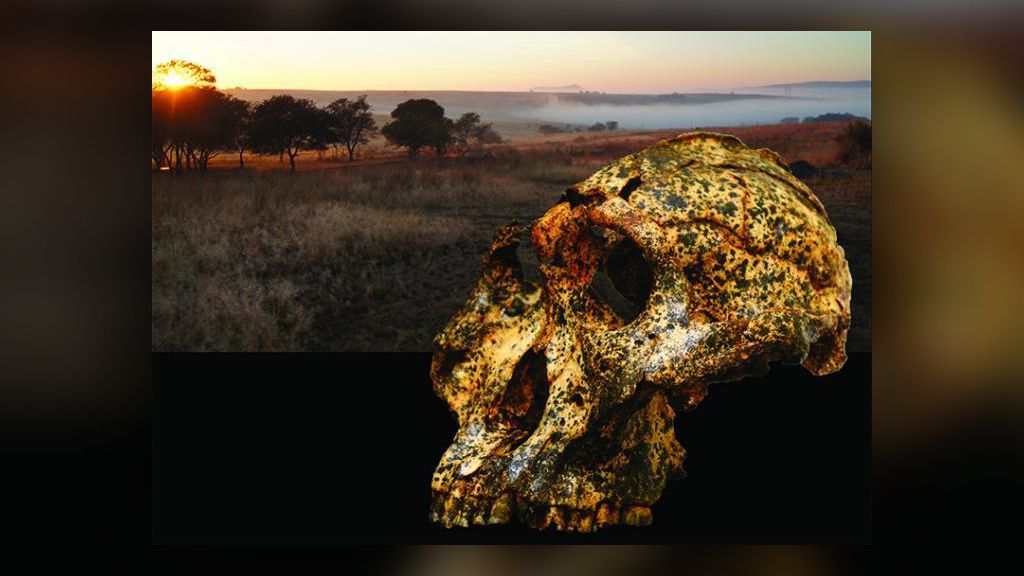

The researchers knew P. robustus since 1938, but the new fossil find – a male skull discovered on June 20, 2018, which earned it the nickname Father’s Day fossil – sheds new light on the species. Based on previous findings, scientists knew this P. robustus was a broad-toothed, small-brained hominin (a group that includes humans, our ancestors, and our close evolutionary cousins) who lived at the same time as other human ancestors, including Standing man is Australopithecus, Live Science previously reported.

For the new discovery, unearthed in the main Drimolen quarry north of Johannesburg, the researchers digitally scanned fragments of the skull, allowing them to digitally reconstruct it and see anatomical details they might otherwise have missed. This analysis revealed that the male’s skull is actually quite similar to the female P. robustus remains found at the same site. In contrast, at another fossil site known as the Swartkrans cave, males are “noticeably different” from a female previously found at Drimolen, which led to the idea that males shifted heavily over females, Martin said. .

“It now appears that the difference between the two sites cannot be explained simply as differences between males and females, but rather as differences in the population level between the sites,” Martin he said in a statement. “Our recent work has shown that Drimolen predates Swartkrans by about 200,000 years, so we believe it. P. robustus evolved over time, with Drimolen representing an early population and Swartkrans representing a later, more [evolved] population.”

These anatomical changes are the first high-resolution example of microevolution within one of the earliest hominid species, the researchers said. Taken together, the P. robustus fossils show that the only way this species chewed developed incrementally, probably over hundreds of thousands of years. (A study published in 2018 in the journal Royal Society Open Science found that P. robustus He had a unusual “twist” in the roots of the teeth, suggesting that the species chewed with a slight twisting motion and back and forth with its jaw as it ate.)

P. robustus it probably underwent microevolution due to the local climate change, when what is now South Africa was drying up. Previously, researchers knew this soon after P. robustus appeared, Australopithecus became extinct. In that time Standing man also emerged in that region. This transition occurred rapidly, evolutionarily speaking, probably in the order of a few tens of thousands of years.

“The working hypothesis was that climate change has created stress in the populations of Australopithecus eventually leading to their disappearance, but for which environmental conditions were more favorable Homo is Paranthropus, which may have dispersed into the region from elsewhere, “co-researcher David Strait, a professor of biological anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis, said in the statement.” Now we see what the environmental conditions were probably stressful for Paranthropus and that they needed to adapt to survive. “

Due to microevolution, it appears that P. robustus Co-researcher Angeline Leece, an archaeologist at La Trobe University, probably developed a chewing ability that could grind resistant plants, such as tubers.

The study was published online Nov.9 in the journal Nature, ecology and evolution.

Originally published in Live Science.

Source link