[ad_1]

There is no real reason why most of us need to know what the Moon will look like on any given day at any given time in the next year. No reason other than intellectual curiosity, that is. So, if you have a good supply of it, then you’ll enjoy NASA’s latest contribution to fixing the internet and wondering where the time has gone.

In fact, that might be a little unfair. Like almost everything NASA produces, it is instructive. This year-round animation of the Moon does a good job of illustrating the idea of lunar libration and how it shows us a slightly different portion of the Moon throughout the year.

There are actually two animations, both in 4K. One is an animation of the view from the northern hemisphere of the Earth and one is from the south. Each takes about five minutes.

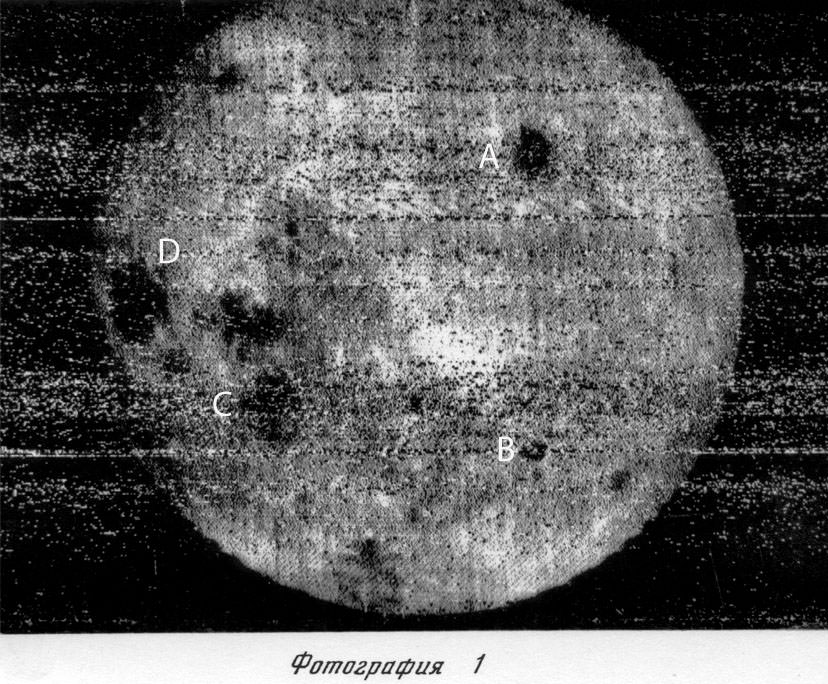

Most of us know that the Moon is firmly attached to the Earth. This means that the side facing the Earth has been invisible for most of human history. It is only thanks to the space race that we finally saw it. In October 1959 the USSR unmanned spacecraft Luna 3 was the first to take pictures of the opposite side of the Moon and transmit the photos to us.

So with half of the Moon’s surface out of sight, that means we can only see 50% of the surface from Earth, right? Not exactly.

Thanks to the lunar libration, we can actually see just over 50%. Not all at once, of course. But over time, we can see up to 59% of our satellite. The Moon has a slight north-south wobble and a slight east-west wobble, and these actions change which part of the Moon we can see at any given moment.

This short animation shows the effect of libration.

The animations clearly show the effect of both latitudinal and longitudinal release. If you focus on Tycho Crater, the large crater at the bottom of the Moon, it really does the point.

The rotation of the Moon helps explain its libration. Yes, even if the Moon is tidal locked, it still rotates. We cannot say this because its rotation lasts as long as its orbit around the Earth: 27.32 days. This is called synchronous rotation and many moons in the Solar System exhibit the same behavior.

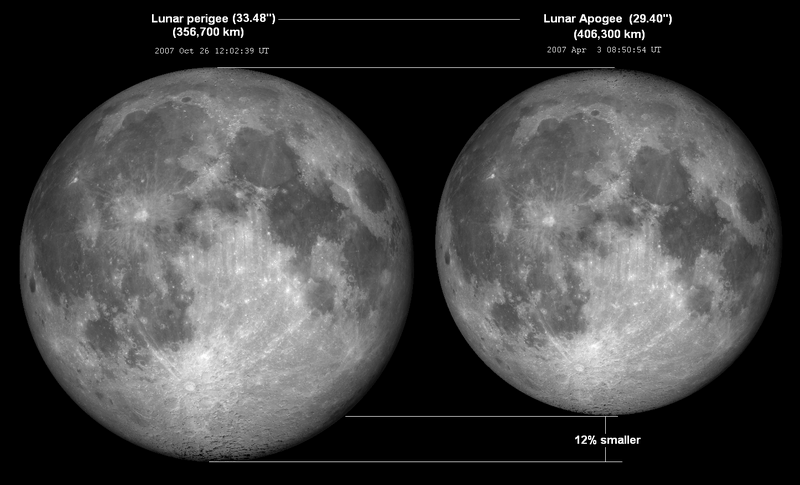

In the animation we can clearly see the Moon getting bigger and then shrinking. This is because the orbit of the Moon has an apogee and a perigee; points when it is farthest from Earth, therefore closer to Earth. Although the rotation speed of the Moon remains the same, its orbital speed changes. At perigee its orbit is faster and at apogee it is a little slower.

These changes in orbital velocity mean that longitudinal librations are at their maximum about one week after the perigee and one week after the apogee. After the perigee (closest point), the rotation of the Moon falls behind its orbit and after the apogee (farthest point) the orbit cannot keep up with the rotation. This exposes about another 8 degrees of the Moon to view.

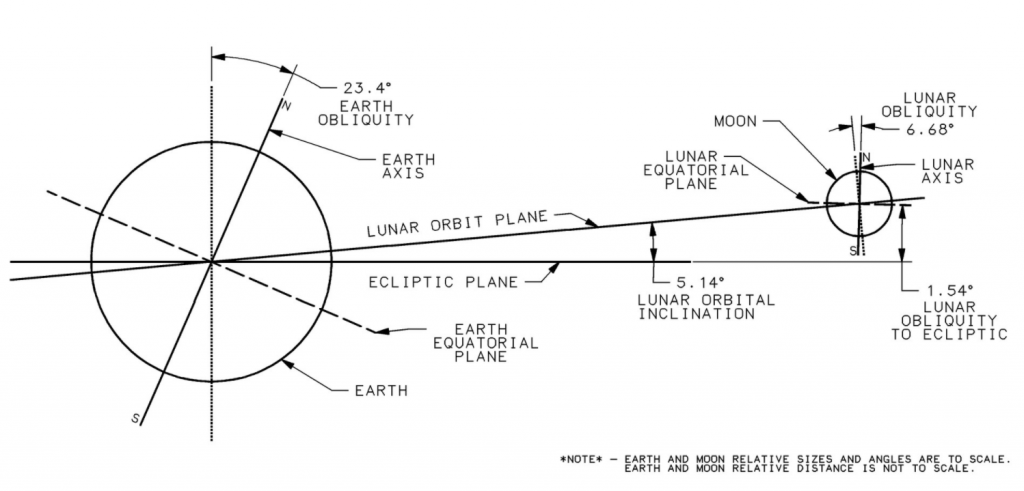

There is also the latitidunale libration due to the axial inclination of the Moon. With respect to the Earth’s orbital plane, the ecliptic, the Moon is tilted about 5 degrees in its orbital plane, and its equatorial tilt adds another 1.5 degrees of tilt, approximately.

When the Moon crosses the Earth’s ecliptic, it is called a node. This happens twice a month, and when the Moon travels north through the ecliptic, it is called the ascending node, and when it travels south, it is called the descending node. The latitudinal librations of the Moon are most pronounced during the week after each node.

So, after the Moon crosses the ecliptic to the north, it is exposed a little more than the south pole region of the Moon. After crossing south, it is slightly more exposed than the north pole. At certain times more than 7 degrees beyond the poles are visible. Simple, right?

Your position on Earth also affects which part of the Moon you can see. But this doesn’t have much to do with the Moon itself. If you’d rather see more of the Moon’s north pole region, move to the Northern Hemisphere of the Earth.

Fortunately for us, it no longer matters where we live on Earth. We have an almost unlimited view of the Moon thanks to telescopes and satellites.

But knowing these details of the Moon and its movement and its relationship to the Earth makes the Moon more “alive” and makes us think about things a little more deeply.

Mission accomplished, NASA.

Source link