[ad_1]

[ad_1]

In Africa, the demand for electricity far exceeds supply. Nigeria's scarcity of 173,000 MW (for a nation whose current energy needs are around 180,000 MW) has given rise to large-scale imports of noisy and polluting power generators.

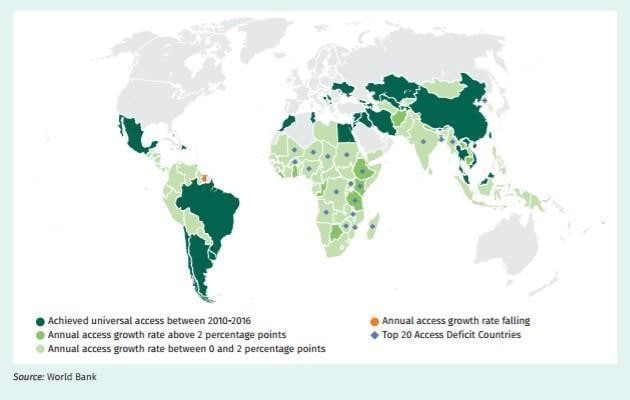

Annual increase in the rate of access to electricity in 2010-2016 in countries where the demand for electricity exceeds supply.

Most Sub-Saharan African countries have the same experience. In rural Rwanda, where more than 70% of the population live, only 18% of the population has access to electricity. A large number of families and public buildings in rural communities are not connected to their state-supported electricity grid. City dwellers and medium-sized businesses connected to the network can not yet be sure of having electricity all day. The Government of Rwanda has set a goal to achieve successful electrification by 2024.

The cost of generating and distributing energy is high. Economic and political reasons mean that it will take a lifetime to consider these communities. The Objective no. 7 for the sustainable development of the United Nations, aimed at universal access to energy for all by 2030, among other international agreements is determining a global consensus on renewable energy in off-net communities.

In several African countries, renewable energy has been at the center of the development and investment strategy. Huge investments and the support of the African Development Bank (AfDB), Overseas Private Investment Corporation and the World Bank in Photovoltaics and Wind Energy are achieving results.

This is because the easiest and most cost-effective way to obtain electricity in rural communities in Africa is with a decentralized energy source, like photovoltaics and wind energy. These communities, which are not connected to the national grid, will relieve the government's burden of investing in large-scale plants to meet the growing demand for electricity.

Togo, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo are doing well in setting up policies and regulatory frameworks in this area. In an ambitious plan to achieve universal access to energy across the continent by 2025, AfDB mobilizes capital to help realize the potential of the continent to generate at least 160 GW by 2025.

While this is commendable, experts say that the penetration of the green energy market in Africa is low and, so far, the success of electrification plans focuses on the number of connections made and on the megawatts installed rather than on the 39; final use of that power.

There is, however, a continuous change in how to measure the success of electrification. In Africa, communities must have appliances, classrooms, equipment, irrigation systems, and so on, ready and available to be powered by electricity. The energy supplied must meet a demand that increases productivity.

There is no need to expand decentralized energy if the end use does not improve lives and meets critical needs. The World Bank is using this same measure to monitor progress in access to electricity.

Innovation to accelerate access through decentralized energy is moving more towards demand management and distribution, using connectivity and data.

With the emergence of the blockchain (a protocol that eliminates intermediaries), it is possible to establish a controlled and verifiable register that can record energy consumption, credit history (which is relevant when funding is required from access), as well as providing energy exchanges between families; give consumers more control over their energy needs and consumption.

In 2017, a non-profit Energy Web Foundation (EWF) started developing a scalable and open source blockchain platform with the goal of creating a market standard for the energy sector to develop and manage its solutions based on blockchain.

The first use case of EWF, EW Origin, creates a market in which all the smart meters of solar photovoltaics can communicate. It also records the origin of the electricity produced from renewable sources, with clear details on the type of source, time, location and CO2 emissions. This provides a universal dashboard that tracks the world's energy consumption.

A recent project by the Microgrid in Brooklyn offers its participants the possibility to choose the preferred source of energy locally. Using a mobile app, Exergy, residents with rooftop photovoltaic panels (so-called prosumers) can sell excess solar photovoltaics to residents without photovoltaic solar panels connected to the micro-grid. Safe trading is made possible by blockchain. Platforms like these help small energy consumers to reach electricity and financial inclusion.

The moves to achieve universal access to energy for everyone in Africa can not be superficial. The commitment to the success of electrification should be strengthened through mutually beneficial collaboration between public and private entities. Successful collaboration between these actors will come from shared interests, openness in investments and use of innovative solutions; and there should also be active participation of citizens.

A "business as usual" attitude will not change the energy prospects of Africa. Using a technology that allows shared consent on a transparent but secure context it will. First of all, Blockchain will inspire a rapid adoption of the decentralized energy system in places with or without electricity. Secondly, not only will productivity increase among small energy consumers, but new ways of defining the final use of energy will emerge.

To share