[ad_1]

The surface of the Sun is a turbulent dance of gravity, plasma and magnetic fields. Just like the weather on Earth, its behavior may seem unpredictable, but there are patterns to find when you look closely.

The first pattern to be observed on the solar surface was that of sunspots. Sunspots were noticed by some ancient astronomers, but have been regularly studied since the 1600s.

While astronomers have counted the number of spots seen each year, they have found that the Sun goes through active years and quiet years. There is an 11-year cycle of high and low sunspot counts. There are other cycles too, such as the Gleisberg cycle, which lasts 80-90 years.

These patterns are similar to the tornado seasons of the American Midwest or the El Niño / La Niña cycles of the Pacific. These great models have a regularity that makes them easy to anticipate.

But while predicting sunspot cycles is relatively easy, predicting the appearance of a single sunspot is not.

One of the challenges with sunspot prediction is that we can’t place sensors directly on the Sun’s surface. Measuring the magnetic fields that create sunspots is difficult.

But astronomers have learned that the Sun can be studied using sound waves, and this technique is starting to allow them to predict individual sunspots.

One of the projects studying the sun in this way is the Global Oscillation Network Group (GONG). It’s a collection of six solar telescopes that measure the movement of the Sun’s surface 24/7.

The vibrations of the Sun’s surface are caused by sound waves moving through the interior of the Sun. The study of the Sun in this way is known as heliosismology.

Although primarily used to study the solar interior, sound waves are also affected by surface features such as sunspots, and recently the GONG team used this feature to predict one.

About a week ago, the GONG team noticed that the solar acoustic vibrations appeared to be interrupted by a feature on the far side of the Sun. They couldn’t see the feature, but it was consistent with that of a sunspot.

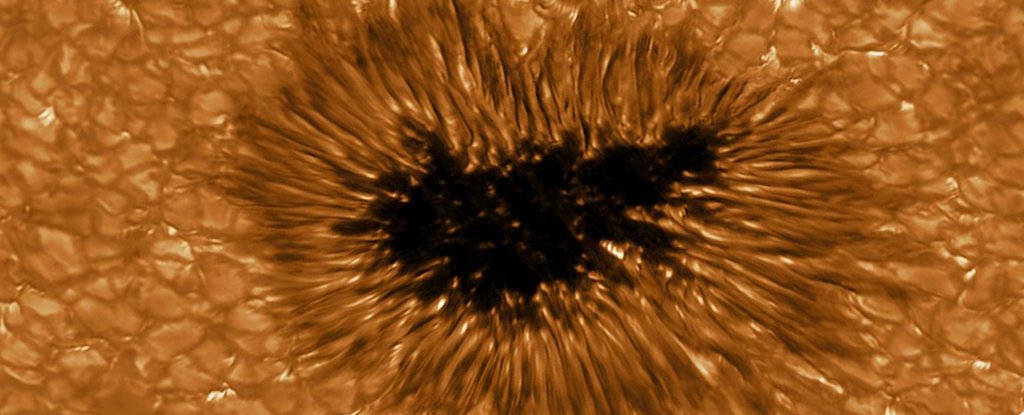

The predicted sunspot cluster, on the left, rotating on the face of the Sun. (NSO / AURA / NSF)

The predicted sunspot cluster, on the left, rotating on the face of the Sun. (NSO / AURA / NSF)

So the team predicted that a sunspot cluster could be visible from Earth around Thanksgiving. And it turned out they were right.

This type of forecasting is extremely useful because large sunspots are often accompanied by other activities such as solar flares.

Intense solar flares can disrupt modern satellites like GPS and, in the most extreme case, could threaten to collapse our power grid. Anticipating these events several days in advance will give us time to mitigate their effects.

With more research, GONG’s team and others may even be able to predict the appearance of sunspots before they form.

This would give us well over a week to prepare for any threats from solar flares and give all of us who use this technology a reason to breathe a little easier.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.

.

[ad_2]

Source link