[ad_1]

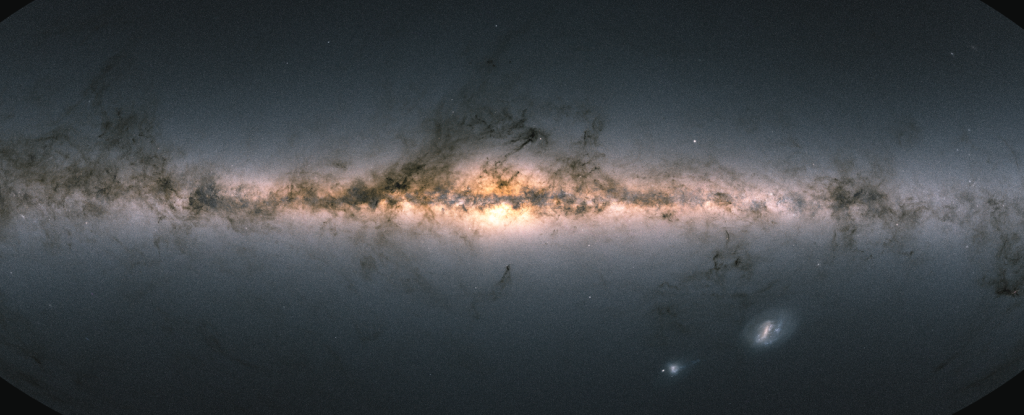

The most accurate three-dimensional map of the Milky Way ever seen is revealing the secrets of our galaxy. Peering deep into the anticenter – the opposite direction to the galactic center – is helping astronomers reconstruct the Milky Way’s wild past.

The European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite, launched in 2013, has been working for years to map the galaxy in the greatest detail and accuracy obtainable. Its new version of data, Gaia Early Data Release 3 (EDR3), is a big improvement over existing data, as demonstrated in a number of new papers published in Astronomy and astrophysics.

In addition to probing the anticenter of the galaxy, the astronomers described the orbit of the Solar System around the galactic center, took a closer look at the Magellanic Clouds orbiting the Milky Way, and performed the largest census of stars of the Milky Way and their movement in the sky.

“The new Gaia data promises to be a treasure trove for astronomers,” said ESA astronomer Jos de Bruijne.

Gaia orbits the Sun with the Earth, in a circular orbit around the Lagrangian point L2 Sun-Earth, a gravitationally stable pocket of space created by the interactions between the two bodies. From there, carefully study the stars in the Milky Way over an extended period, observing how the positions of the stars appear to change relative to more distant stars. This provides a parallax, which can be used to calculate distances to stars.

This can be done from here on Earth, but atmospheric effects can interfere with the measurements. From her position in space, Gaia has an advantage, which she used to great effect.

To date, it has detailed 1.8 billion sources and collected color information on 1.5 billion sources. According to ESA, this is an increase of 100 million and 200 million sources from Data Release 2 in 2018.

Of particular interest is the anticenter of the Milky Way. This region is not as densely populated as the galactic center, nor is it obscured by interstellar clouds of thick dust, offering a clearer view of the stars at the edge of the Milky Way.

(ESA / Hubble, sketch: ESA / Gaia / DPAC)

(ESA / Hubble, sketch: ESA / Gaia / DPAC)

This region more clearly shows the disturbances inflicted on the Milky Way over its history, and by studying the new data, astronomers concluded that the galaxy’s disk was smaller than it is today.

Interestingly, the older stars – the original population of the Milky Way – do not extend to the stars of Gaia Sausage, a galaxy that merged with the Milky Way 8 to 10 billion years ago.

When you look above and below the galactic plane, a different picture emerges. A cluster of stars above the plane is moving down and the stars below are moving up. This, according to the analysis, could be the result of a slow ongoing collision with the dwarf galaxy of Sagittarius, which ruffles the outer edge of the Milky Way’s disk.

The Sagittarius galaxy, according to a paper released earlier this year based on Gaia DR2, is likely causing deformation in the Milky Way’s disk as it moves. Its last close encounter is difficult to narrow down, but it took place between 300 and 900 million years ago, producing some severe perturbations.

Although unexpected, the strange movements of the stars seen in EDR3 could be further evidence of the ongoing interaction between the two galaxies, as determined by simulations that match the observations.

Gaia’s point of view on the Magellanic Clouds. (ESA / Gaia / DPAC; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

Gaia’s point of view on the Magellanic Clouds. (ESA / Gaia / DPAC; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

It is not the only violence that Gaia has confirmed. The Milky Way has two companions, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, which orbit each other as they also move around the Milky Way. Eventually, these too will merge into the Milky Way, but are also engaged in interactions with each other.

In the Gaia data, astronomers observed in greater detail a stream of stars called the Magellanic Bridge being pulled from the Small Magellanic Cloud to the Large Magellanic Cloud. They also clearly observed the spiral structure of the Large Magellanic Cloud and found tantalizing clues of previously invisible structures at the outer edges of both clouds.

The movement of the Solar System has also undergone a slight revision. By observing the movements of distant galaxies, astronomers were able to calculate the acceleration of the Solar System relative to the rest of the Universe. This gave us the first measure of the curvature of the Solar System’s orbit around the center of the Milky Way.

And a new census of stars within 100 parsecs (326 light years) of the Solar System is the most complete yet. It contains 331,312 stars, about 92 percent of all stars within that distance. The Gaia catalog of nearby stars should provide an invaluable reference point for astronomy.

Based on previous Gaia data releases, we’ve learned a lot about our home galaxy, including some fascinating surprises, such as the largest gas structure in the Milky Way, stellar streams hidden by ancient collisions, and a new estimate of the size of the Milky Way (era much bigger than we thought!).

EDR3 will expand this knowledge and Gaia, although she is nearing the end of her mission, is not done yet. EDR3 is only the first part of the data release. The second part will arrive in 2022.

The satellite will also retire in 2022. But it will do so having irrevocably changed astronomy and our understanding of space around us.

The documents were published in Astronomy and astrophysicsand the data release can be found here.

.

[ad_2]

Source link