[ad_1]

During the Cambrian period, the oceans of the world teemed with strange, swimming and segmented creatures.

Over the course of millions of years, these elongated, millipede-like animals would evolve to become modern arthropods: crustaceans like crabs, arachnids like scorpions, and insects like bees and ants.

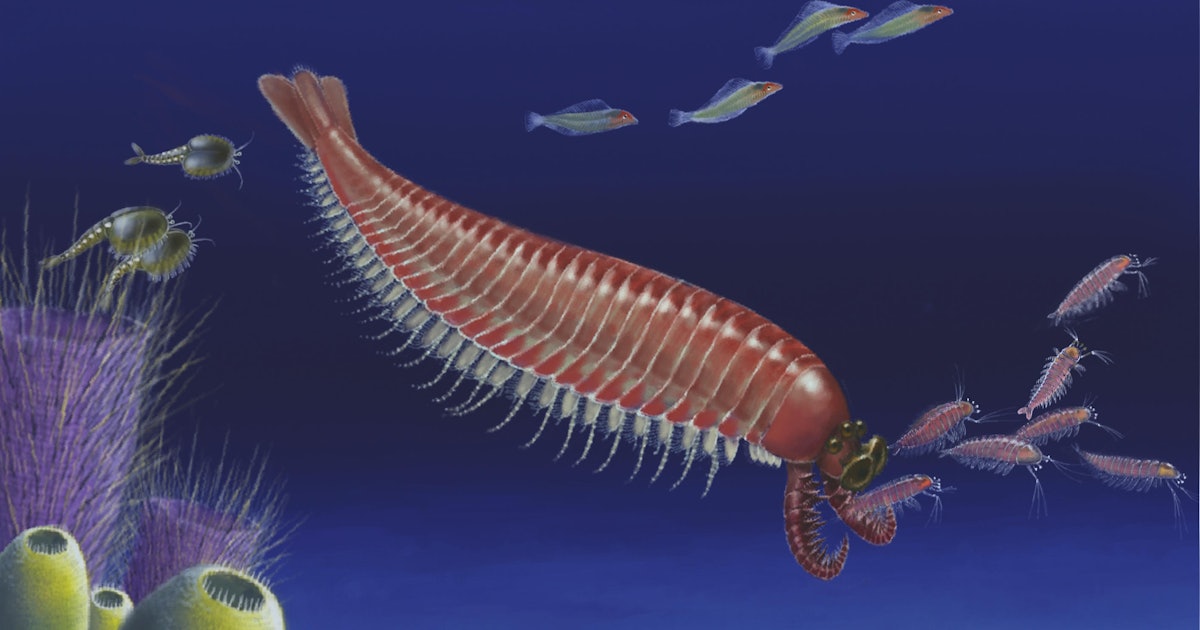

But some 500 million years ago, these Cambrian aquatic beasts were rather more experimental when it came to their physical traits and body planes than their more familiar descendants. It was 3 feet long Opabinia, with 5 eyes balanced on stems and elephant trunk mouth, and the predator Radiodonta species, filled with two spiny, curved and segmented appendages designed to capture prey.

But there was another creature swimming around Earth’s oceans, showing both of these strange characteristics, and much more. Enter the Kylinxia zhangi.

This newly discovered shrimp species is featured in an article published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

In the paper, the researchers reveal that rather than a special feature, this small fossil arthropod possesses a melting pot of physical traits, including five eyes on curved, thorny stems and hooks that extend upward from the front of its body like claws. It looks like it was also armored. The fossil has a fused head shield, an armored, segmented body, and other claw-like appendages along its shell.

The discovery helps scientists understand how Cambrian arthropods may have been related to each other and how their legacy survives today in crabs and insects.

Diying Huang is a co-author of the article and a professor at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. He says Reverse that while modern arthropods may seem like a diverse group, they have nothing about their ancient ancestors.

“Modern arthropods are abundant and diverse. They are everywhere and familiar [to] people, “he says.” Cambrian arthropods are also complex, not just diversity, [but] also morphology, anatomy and functional morphology. “

In a nod to its strange physiology, the researchers dubbed the new shrimp Kylinxia zhangi, takes its name Kylin, a Chinese mythological chimera. And while its mismatched body is curious, it’s also a rare sign of a pivotal moment in the evolution of ancient animals. Chilinxia it can be a kind of “transition”, able to shed light on the evolutionary relationships between other animals living at the same time.

“[These] groups would [have] lived at the same or a similar time in the Cambrian Sea, “says Huang.” They could have [the] the same ancestor at an earlier time. “

Researchers use a process called phylogenetic analysis to try to reconstruct, based on its strange physiology, Chilinxia‘S evolutionary path among arthropods. The analytic technique pays attention to details such as how many segments a creature has, the shape of its head, or how pointed its appendages are. Similarities between animals are assumed to be more likely based on evolutionary relationships than on chance.

The fact that Chilinxia they possess thorny and hunting appendages shaped like those of Radiodonta, combined with the fact that these are upside down, like another arthropod, Megacheira, it’s at Megacheira-like a body, leads researchers to believe it Radiodonta is Megacheira inherited their appendages from a common ancestor, rather than independently evolving into each creature.

In other words, it’s the same creepy appendix, just turned upside down.

Addition Chilinxia the ancient tree also sheds light on the evolution of modern arthropods. Previous work had suggested this Megacheira, with their thorny appendages, were closely related to Chelicerata, the group that includes modern scorpions and spiders, as well as a group of ancient animals with antennae, which may have evolved into insects, such as bees and ants.

The thorny appendages Megacheira, the mouth pinchers on scorpions and spiders and the antennae on bees are all found similarly on the bodies of these animals, leading researchers to believe they may all have evolved from one or more creatures with similar structure.

But the researchers didn’t know what came first. Did the thorny appendages evolve into antennae, which evolved into pinchers? Or were they the mouthparts first? The discovery of Chilinxia ages the spiny appendages, suggesting that they gave rise both pincers and antennae along separate lineages, rather than mouthparts derived from antennae, or vice versa.

The underwater world of little Chilinxia, whirling of segmented beasts, many appendages, is very different from that of modern oceans. But the diverse morphological and ecological experimentation of early arthropods like this “probably laid the foundation for their later evolutionary successes,” the researchers say.

Abstract: Solving the early evolution of euarthropods is one of the most challenging problems in metazoic evolution1,2. Exceptionally preserved fossils from the Cambrian period have provided important paleontological data to decipher this evolutionary process3,4. Phylogenetic studies have resolved Radiodonta (also known as anomalocarididi) as the closest group to all euarthropods that have frontal appendages on the second segment of the head (Deuteropoda) 5-9. However, the interrelationships between major Cambrian groups of euarthropods remain controversial1,2,4,7, which impedes our understanding of the evolutionary gap between Radiodonta and Deuteropoda. Here we describe Kylinxia zhangi gen. et. sp. nov., a euartropod from the first Chinese biota of Chengjiang in the Cambrian. Chilinxia possesses not only deuteropod features such as a fused head shield, a fully arthrodized trunk and articulated endopodites, but also five eyes (as in Opabinia) and radiodont-like rapacious frontal appendages. Our phylogenetic reconstruction recovers Kylinxia as a transitional taxon linking Radiodonta and Deuteropoda. The more basal deuteropods are recovered as a paraphyletic lineage that features plesiomorphic rapacious frontal appendages and includes chilinxia, megacheirans, panchelicerates, “large appendix” bivalve euarthropods and isoxides. This phylogenetic topology supports the idea that the radiodont and megacheiran frontal appendages are homologous, that the Chelicerata chelicerae originated from large megacheiran appendages, and that the sensory antennae in Mandibulata derived from ancestral rapacious forms. Chilinxia thus provides important insights into the phylogenetic relationships between early euarthropods, the evolutionary transformations and disparity of the frontal appendages, and the origin of crucial evolutionary innovations in this clade.

Source link