[ad_1]

The way companies drill oil and gas and dispose of wastewater can trigger earthquakes, sometimes in unexpected places.

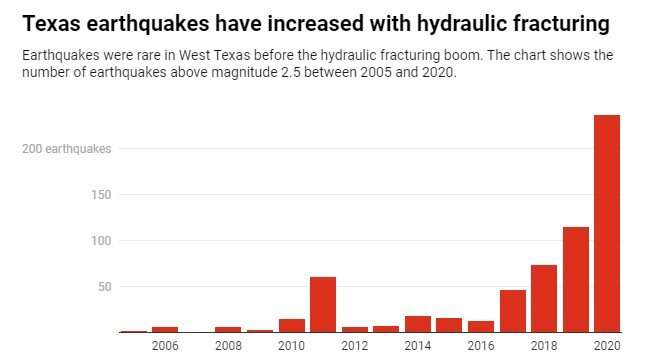

In West Texas, earthquake rates are now 30 times higher than they were in 2013. Studies have also linked earthquakes to oil field operations in Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado and Ohio.

California was thought to be an exception, a place where oilfield operations and tectonic faults apparently coexisted without much trouble. Now, new research shows that the state’s natural seismic activity could hide industry-induced earthquakes.

As a seismologist, I have studied induced earthquakes in the United States, Europe and Australia. Our latest study, released on November 10, shows how California’s oilfield operations are putting stress on tectonic faults in an area just miles from the San Andreas fault.

Credit: The Conversation

Seismic impulse

Industry-induced earthquakes have been a growing concern in the central and eastern United States for more than a decade.

Most of these earthquakes are too small to be felt, but not all. In 2016, a magnitude 5.8 earthquake damaged buildings in Pawnee, Oklahoma, and led state and federal regulators to close 32 sewage disposal wells near a recently discovered fault. Large earthquakes are rare far from the boundaries of the tectonic plates, and Oklahoma having experienced three earthquakes of magnitude 5 or greater in one year, as in 2016, was unheard of.

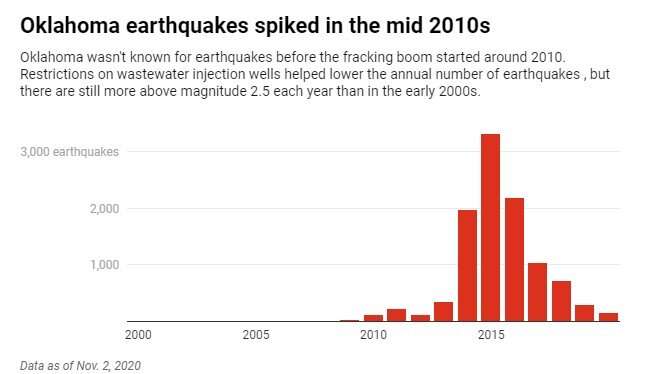

The frequency of earthquakes in Oklahoma has decreased with lower oil prices and the decision by regulators to require companies to reduce the volume of injection into wells, but there are even more earthquakes today than in 2010.

A familiar pattern has emerged in West Texas in recent years: the drastic increase in earthquake rates far beyond the natural rate. A magnitude 5 earthquake shook West Texas in March.

How does it work

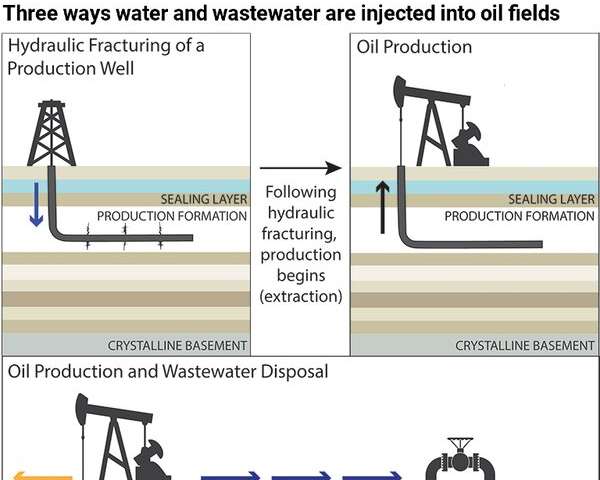

At the root of the induced earthquake problem are two different types of fluid injection operations: hydraulic fracturing and wastewater disposal.

Hydraulic fracturing involves injecting water, sand, and chemicals at very high pressures to create flow paths for hydrocarbons trapped in narrow rock formations. Wastewater disposal involves injecting fluids into deep geological formations. Although wastewater is pumped at low pressures, this type of operation can disturb natural pressures and strains over large areas, several miles from injection wells.

The tectonic faults under geothermal and oil fields are often precariously balanced. Even a small perturbation of the natural tectonic system, for example due to the injection of liquids at depth, can cause the slipping of faults and trigger earthquakes. The consequences of liquid injections are easily seen in Oklahoma and Texas. But what are the implications for other places, like California, where earthquake-prone faults and oil fields are in close proximity?

Credit: US Geological Survey

The hidden risk of California’s oil fields

California offers a particularly interesting opportunity to study the effects of fluid injection.

The state has a large number of oil fields, earthquakes, and many instruments that detect even small events, and was thought to be largely free of unnatural earthquakes.

My colleague Manoo Shirzaei of Virginia Tech and I wondered whether the induced earthquakes could be masked by nearby natural earthquakes and therefore had not been detected in previous studies. We conducted a detailed seismological study of the Salinas Basin in central California. The study area is distinguished by its proximity to the San Andreas fault and because the waste fluids are injected at high speed near the seismically active faults.

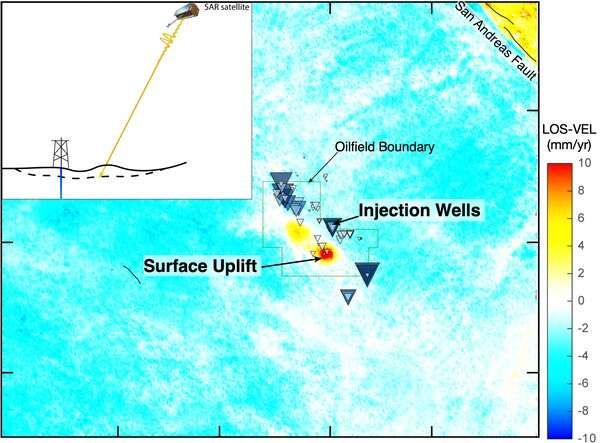

Using satellite radar images from 2016 to 2020, Shirzaei made a startling observation: some regions in the Salinas Basin were rising at about 1.5 centimeters per year, just over half an inch. This increase was an early indication that fluid pressures are unbalanced in parts of the San Ardo oil field. The increase in fluid pressure in the rock pores stretches the surrounding rock matrix like a sponge being pumped full of water. The resulting expansion of the reservoir elevates the forces acting on the surrounding tectonic faults.

-

Satellite data shows that the ground rises up to 1.5 centimeters per year in parts of the San Ardo oil field. The line of sight velocity (LOS-VEL), as seen from the satellite, shows how quickly the ground surface is rising. Credit: Thomas Goebel / University of Memphis

-

The stresses deriving from the injection of water can trigger earthquakes several kilometers from the well itself. The blue triangles adapt to the injection rate of each well. Credit: Thomas Goebel / University of Memphis, CC BY-ND

Next, we looked at the seismic data and found that fluid injection and earthquakes were highly correlated for over 40 years. Surprisingly, this stretched 15 miles from the oil field. These distances are similar to the large spatial footprint of injection wells in Oklahoma. We analyzed the spatial pattern of 1,735 seismic events within the study area and found a clustering of events near the injection wells.

Other areas of California may have a similar history and more detailed studies are needed to differentiate natural from induced events.

How to reduce the risk of an earthquake

Most sewage disposal and hydraulic fracturing wells do not lead to earthquakes that can be felt, but wells that cause problems have three things in common:

Although the former problem may be difficult to solve as reducing the volume of waste fluids would require reducing the amount of oil produced, the locations of the injection wells can be planned more carefully. The seismic safety of oil and gas operations can be increased by selecting geological formations disconnected from deep faults.

What Factors Affect the Likelihood of Fracking-Related Seismicity in Oklahoma?

Provided by The Conversation

This article was republished by The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Quote: Operations on oil fields likely triggered earthquakes in California a few miles from the San Andreas fault (2020, November 11) recovered November 11, 2020 from https://phys.org/news/2020-11-oil-field -triggered-earthquakes- california.html

This document is subject to copyright. Aside from any conduct that is correct for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.

[ad_2]

Source link