[ad_1]

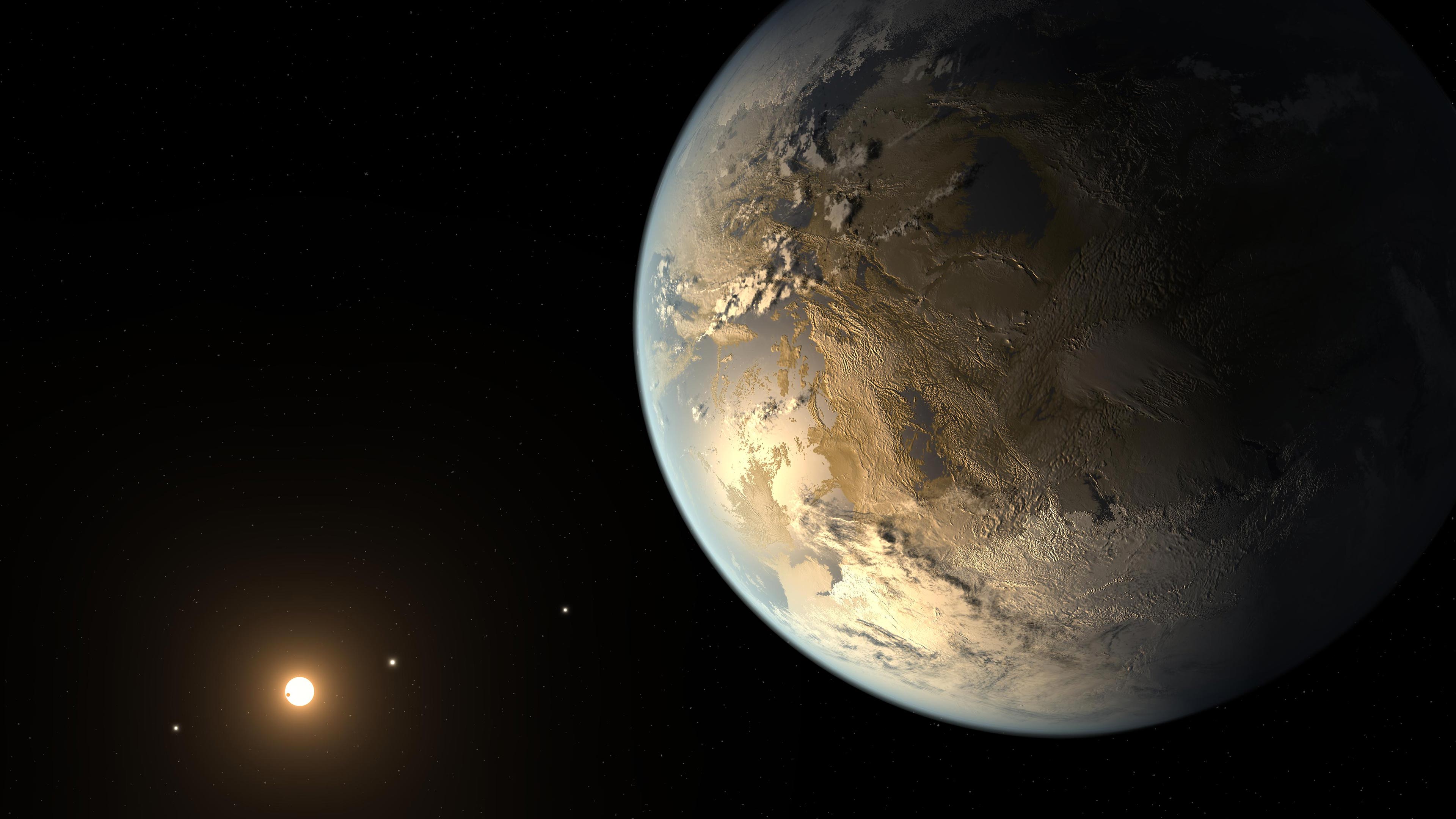

This illustration shows Kepler-186f, the first validated Earth-sized planet to orbit a distant star in the habitable zone. Credit: NASA Ames / JPL-Caltech / T. Pyle

Ever since astronomers confirmed the presence of planets beyond our solar system, called exoplanets, humanity has wondered how many could host life. We are now one step closer to finding an answer. According to new research using data from NASAThe retired planet-hunting mission, the Kepler Space Telescope, about half of the stars with a similar temperature to our Sun could have a rocky planet capable of supporting liquid water on its surface.

Our galaxy holds at least about 300 million of these potentially habitable worlds, based also on the more conservative interpretation of the results of a study to be published in The Astronomical Journal. Some of these exoplanets may even be our interstellar neighbors, with at least four potentially within 30 light-years of our Sun and the closest probably about 20 light-years away from us. These are the minimum numbers of such planets based on the more conservative estimate that 7% of the Sun-like stars host such worlds. However, at the expected average rate of 50%, there could be many more.

This research helps us understand the potential for these planets to have the elements to sustain life. This is an essential part of astrobiology, the study of the origins of life and the future in our universe.

The study is signed by NASA scientists who worked on the Kepler mission together with collaborators from around the world. NASA withdrew the space telescope in 2018 after it ran out of fuel. Nine years of telescope observations have revealed that there are billions of planets in our galaxy – more planets than stars.

“Kepler had already told us there were billions of planets, but now we know that a good portion of those planets could be rocky and habitable,” said lead author Steve Bryson, a researcher at NASA’s Ames Research Center. California’s Silicon Valley. “Although this achievement is far from being a final value and water on a planet’s surface is only one of many factors that support life, it is extremely exciting that we have calculated that these worlds are so common with such high safety and security. precision.”

For the purpose of calculating this rate of occurrence, the team looked at exoplanets between 0.5 and 1.5 times that of Earth, shrinking to planets that are most likely rocky. They also focused on stars similar to our Sun in age and temperature, roughly up to 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit.

It is a vast array of different stars, each with its own particular properties that influence whether the rocky planets in its orbit are able to support liquid water. These complexities are partly why it’s so difficult to calculate how many potentially habitable planets there are out there, especially when even our most powerful telescopes can barely detect these tiny planets. That’s why the research team took a new approach.

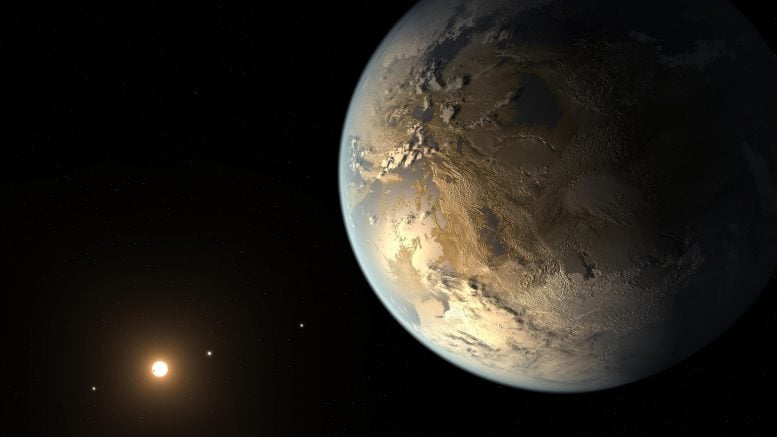

This illustration shows a possible appearance of the planet Kepler-452b, the first Earth-sized world that is in the habitable zone of a star similar to our Sun. Credit: NASA Ames / JPL-Caltech / T. Pyle

Rethinking how to identify habitability

This new discovery is a significant step forward in Kepler’s original mission to understand how many potentially habitable worlds exist in our galaxy. Previous estimates of the frequency, also known as the occurrence rate, of such planets ignored the relationship between the star’s temperature and the type of light emitted by the star and absorbed by the planet.

The new analysis takes these relationships into account and provides a more complete understanding of whether or not a given planet may or may not be able to support liquid water and potentially life. This approach is made possible by combining Kepler’s final data set on planetary signals with data on the energy production of each star from an extensive data collection from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission.

“We have always known how to define habitability simply in terms of a planet’s physical distance from a star, so that it wasn’t too hot or cold, it left us speculating a lot,” said Ravi Kopparapu, an author of the paper and a NASA scientist Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “Gaia’s star data allowed us to look at these planets and their stars in a whole new way.”

Gaia provided information on the amount of energy that falls on a planet from its host star based on a star’s flux, or the total amount of energy that is emitted in a certain area over a certain time. This allowed the researchers to approach their analysis in a way that recognized the diversity of the stars and solar systems in our galaxy.

“Not all stars are the same,” Kopparapu said. “Nor all the planets.”

Although the exact effect is still being researched, a planet’s atmosphere calculates the amount of light needed to allow liquid water even on a planet’s surface. Using a conservative estimate of the effect of the atmosphere, the researchers estimated an occurrence rate of about 50%, meaning about half of the Sun-like stars have rocky planets capable of harboring liquid water on their surfaces. An alternative optimistic definition of the habitable zone estimates around 75%.

An illustration representing the legacy of NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope. After nine years in deep space collecting data that revealed our night sky was filled with billions of hidden planets – more planets even than stars – NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope ran out of fuel for further scientific operations in 2018. Credits: NASA / Wendy Stenzel / Daniel Rutter

Kepler’s legacy charts indicate future research

This result builds on Kepler’s long legacy of data analytics work to get a rate of occurrence and sets the stage for the future. exoplanet observations informed by how common we now expect these rocky and potentially habitable worlds to be. Future research will continue to refine the rate, informing about the likelihood of finding these types of planets and fueling plans for the next stages of exoplanet research, including future telescopes.

“Knowing how common the different types of planets are is extremely valuable in designing upcoming exoplanet research missions,” said co-author Michelle Kunimoto, who worked on this paper after finishing her PhD on exoplanet occurrence rates. at the University of British Columbia, and recently joined the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “Surveys targeting potentially habitable small planets around sun-like stars will depend on results like these to maximize their chances of success.”

After revealing more than 2,800 confirmed planets outside our solar system, data collected by the Kepler Space Telescope continues to yield important new discoveries about our place in the universe. Although Kepler’s field of view only covered 0.25% of the sky, the area that would be covered by your hand if you held it at arm’s length towards the sky, his data allowed scientists to extrapolate what the data mean. of the mission for the rest of the galaxy. This work continues with TESS, NASA’s current planet-hunting telescope.

“For me, this result is an example of what we were able to discover with just that little glimpse beyond our solar system,” Bryson said. “What we see is that our galaxy is fascinating, with fascinating worlds and some that may not be too different from ours.”

Reference: “The Occurrence of Rocky Habitable Zone Planets Around Solar-Like Stars from Kepler Data” by Steve Bryson, Michelle Kunimoto, Ravi K. Kopparapu, Jeffrey L. Coughlin, William J. Borucki, David Koch, Victor Silva Aguirre, Christopher Allen , Geert Barentsen, Natalie. M. Batalha, Travis Berger, Alan Boss, Lars A. Buchhave, Christopher J. Burke, Douglas A. Caldwell, Jennifer R. Campbell, Joseph Catanzarite, Hema Chandrasekharan, William J. Chaplin, Jessie L. Christiansen, Jorgen Christensen-Dalsgaard , David R. Ciardi, Bruce D. Clarke, William D. Cochran, Jessie L. Dotson, Laurance R. Doyle, Eduardo Seperuelo Duarte, Edward W. Dunham, Andrea K. Dupree, Michael Endl, James L. Fanson, Eric B Ford, Maura Fujieh, Thomas N. Gautier III, John C. Geary, Ronald L Gilliland, Forrest R. Girouard, Alan Gould, Michael R. Haas, Christopher E. Henze, Matthew J. Holman, Andrew Howard, Steve B. Howell , Daniel Huber, Roger C. Hunter, Jon M. Jenkins, Hans Kjeldsen, Jeffery Kolodziejczak, Kipp Larson, David W. Latham, Jie Li, Savita Mathur, Soren Meibom, Chris Middour, Robert L. Morris, Timothy D. Morton, Fergal Mullally, Susan E. Mullally, David Pletcher, Andrej Prsa, Samuel N. Quinn, Elisa V. Quintana, Darin Ragozzine, Solange V. Ramirez, Dwight T. Sanderfer, Dimitar Sasselov, Shawn E. Seader, Megan Shabram, Avi Shporer, Jeffrey C. Smith, Jason H. Steffen, Martin Still, Guillermo Torres, John Troeltzsch, Joseph D. Twicken, Akm Kamal Uddin, Jeffrey E. Van Cleve, Janice Voss, Lauren Weiss, William F. Welsh, Bill Wohler, Khadeejah A Zamudio, agreed, The Astronomical Journal.

arXiv: 2010.14812

[ad_2]

Source link