[ad_1]

Albanerpetontids, or “albies” for short, are the cute salamander-like amphibians you’ve probably never heard of.

Now extinct, Albies had a dream ride. They existed since the Middle Jurassic about 165 million years ago, and probably even earlier. They lived through the era of the dinosaurs (and witnessed their extinction), then experienced the rise of the great apes, before silently disappearing around 2.5 million years ago.

Albie fossils are spread across all continents, including Japan, Morocco, England, North America, Europe, and Myanmar. But until recently, we knew relatively little about what they looked like or how they lived.

New research from me and my colleagues, published today in Science, reveals that these amphibians were the first known creatures to have rapid-fire tongues. This also helps explain why albias were once misidentified as chameleons.

A miniature wonder discovered

The reason albie have remained largely elusive until recently is because they were small. Their light, brittle bones are usually found as isolated jaw and skull fragments, making them difficult to study.

The first nearly complete specimen of albie was found in the marshland deposits of Las Hoyas, Spain, and reported in 1995. Even though it was crushed, it was enough for paleontologists to conclude that albias were unlike any living salamander any other amphibian.

They were completely covered in scales like reptiles, had highly flexible necks like mammals, an unusual jaw joint, and large eye sockets that suggested good vision. Why were the albies so unique?

Mistakes happen

Part of the answer came to light in 2016, when a group of researchers published a paper demonstrating the diversity of lizards found in the Cretaceous forests of what is now Myanmar.

They presented a dozen tiny 99-million-year-old “lizards”, all preserved in amber. Some have even been found with remnants of soft tissue such as skin, claws and muscles, still attached to the resin from the fossil tree.

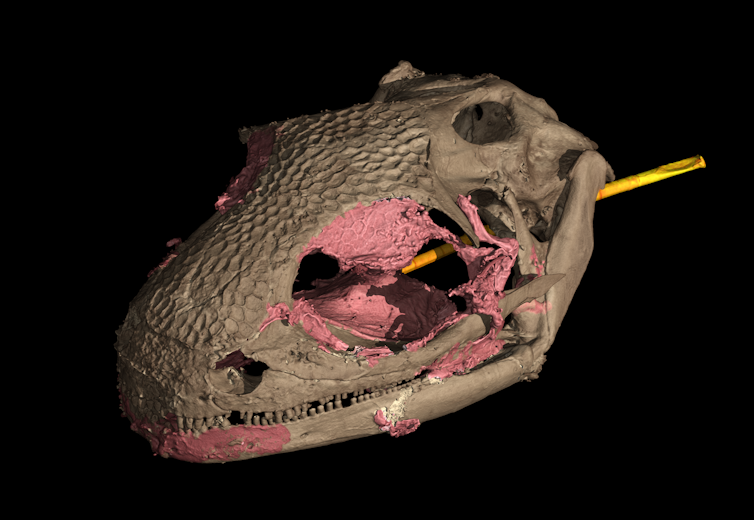

The researchers used “micro-CT” technology to digitally excavate and study the samples in detail. This involved using 3D images to digitally remove the fossil from the amber and study it on a computer, a technique that avoids the risk of physically damaging the fossil.

They noted that a small juvenile specimen had a long rod-shaped tongue bone. It has been identified as the first known chameleon – a remarkable discovery! Or yes?

Unfortunately, errors occur in science. As lizard experts, the researchers had interpreted their results through this lens. It took the keen eye of Susan Evans, professor of vertebrate morphology and paleontology at University College London, to recognize that this particular “lizard” was in fact a misidentified albie.

A hallucinating revelation

Some time later, assistant professor at Sam Houston State University, Juan Daza, spotted another incredible specimen from a collection of fossils preserved in Burmese amber, ethically sourced from the Kachin state of Myanmar.

It was an adult version of the young albie identified by Evans. Needing high resolution 3D images, the sample was sent to me to study at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organization in Melbourne.

It is named after a class of mythical spirits responsible for the safekeeping of natural treasures, Yaksha, and the person who discovered the fossil, Adolf Peretti (founder of the non-profit Peretti Museum Foundation) – the Yaksha perettii the specimen was an entire skull trapped in golden amber.

Quick shots at unsuspecting prey

Its standout features were a long bone protruding back from the mouth and remnants of soft tissue, including part of the tongue, jaw muscles, and eyelids. Luckily, the soft tissue remnants showed that the long mouth bone was attached directly to the tongue.

In other words, Y. perettii he was a predator armed with an incredible weapon: a specialized ballistic tongue that fired at the speed of light to capture prey, just as chameleons do today. No wonder the original youngster, just 1.5 centimeters long, was initially mistaken for a chameleon.

Modern chameleons have accelerating muscles in their tongues that block stored energy. This allows them to shoot with their tongues at speeds of up to 100 kilometers per hour in a split second.

We believe that the bullet tongues of the albie were just as fast, used to great effect while sitting still in trees or on the ground. If so, this also explains why albias had unusual jaw joints, flexible necks, and large forward-facing eyes. All these traits would make up their predatory toolkit.

The sap of the trees has turned to iridescent amber

Despite these extraordinary new insights, however, many mysteries remain of the albanerpetontids. For example, how exactly are they related to other amphibians? How did they survive so long, only to become extinct relatively recently?

We will need more intact specimens to answer these questions. And most of these specimens will likely come from the Hukawng Valley in Kachin, Myanmar.

It is predicted that around 100 million years ago this region was an island covered with vast forests. Global temperatures would then have surpassed those today, with trees producing huge amounts of resin (which later turned to amber) due to damage from insects and fires.

The amber studied by this region will not only increase our knowledge of its expired ecosystems, but it could also provide insight into how some organisms today might evolve in response to a warm climate.![]()

Joseph Bevitt, Senior Instrument Scientist, Australian Organization for Nuclear Science and Technology

This article was republished by The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source link