[ad_1]

Andrew Dempster, UNSW

Water is more abundant on the Moon than we might have suspected, according to two papers published today in Nature Astronomy that confirm the presence of ice on and near the lunar surface.

It’s a push for the prospect of extracting water from the Moon, which can help support humans or be converted into rocket fuel, although the situation is far from simple.

The first document, led by Casey Honniball of the University of Hawaii, offers confirmation of the suspected discovery of water on the Moon. In previous studies, researchers had looked at the frequencies of absorbed radiation and identified the presence of chemicals called hydroxyl ions on the moon.

Hydroxyl ions (OH-) are part of the water molecule H₂0, which means that water ice was a probable, but not defined, source of the detected hydroxyls. But since hydroxyl ions are also found in many other compounds, it was impossible to be sure.

The new research used a new technique and showed that a significant percentage of those hydroxyls are actually found within water ice molecules, possibly bound or suspended in the moon’s surface rocks. More research is needed to deduce the precise details, but the presence of molecular water is big news.

The second paper, led by Paul Hayne of the University of Colorado, notes that there will likely be more “cold traps” containing ice water than previously estimated.

A “cold trap” is a place in permanent shade, where ice can survive because it never receives direct sunlight and where the temperature remains sufficiently low. Elsewhere, sunlight heats ice, making it “sublime”: the Moon’s low atmospheric pressure means that solid ice directly transforms into water vapor, which can refreeze somewhere else.

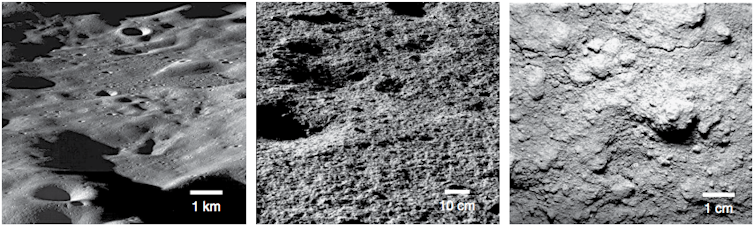

The study showed that at high latitudes there were potentially very large numbers of these cold traps (possibly billions), some as small as 1cm in diameter.

How much water is there on the moon? Current estimates, based on the previous detection of hydroxyls, range from 100 million tons to the most recent 2.9 billion tons. According to the new estimate, up to 30% of some areas of the lunar surface could be frozen in cold traps.

Even using the moderate price of water offered by the launch company ELA of $ 3,000 per kg for delivery in low Earth orbit, the water on the Moon could be worth billions of dollars a year, because water can be split in hydrogen and oxygen and used as rocket fuel. Some of our research shows how a business case can be built in low earth orbit.

The importance of the new findings is that there is now much more certainty that water is there and there are more widespread opportunities to find it.

Good news for ice miners?

It’s a timely discovery, because there has been a lot of activity recently, including in Australia, in developing projects to extract water on the moon. In the past two weeks alone, NASA has granted a contract for an ice-mining exercise and announced the launch aboard NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS), designed for deep space missions, of three small satellites. looking for water. Meanwhile, the European and Chinese space agencies have announced missions to explore the lunar south pole for water.

Australia is in this game due to the Australian Space Agency’s $ 150 million commitment to the Moon to Mars program. Australia also signed the Artemis Agreements this month, a series of bilateral agreements between the United States and other partners to develop a legal framework for space resources.

It might sound like great news, but Australia is also a signatory to the Moon Accord, the United Nations’ approach to peaceful uses of the Moon and other bodies. Some say this is inconsistent with the Artemis agreements. we have called for the Australian Space Agency to provide clarity on this issue and hosted events to discuss it (including a solid one and a half hour debate).

Yet Australia is now a signatory to both agreements, with no explanation as to how this is possible under international law. We need the Australian Space Agency to provide clarity on its interpretation of both instruments as soon as possible. The urgency of this action is pressing: we are now much more certain that there is water to be extracted on the Moon and that the barriers to entry have been lowered. Australian companies are developing capabilities in space resources and need certainty to allow these companies to grow.

Andrew Dempster, Director of the Australian Center for Space Engineering Research; Professor, School of Electrical Engineering and Telecommunications, UNSW

This article was republished by The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[ad_2]

Source link