[ad_1]

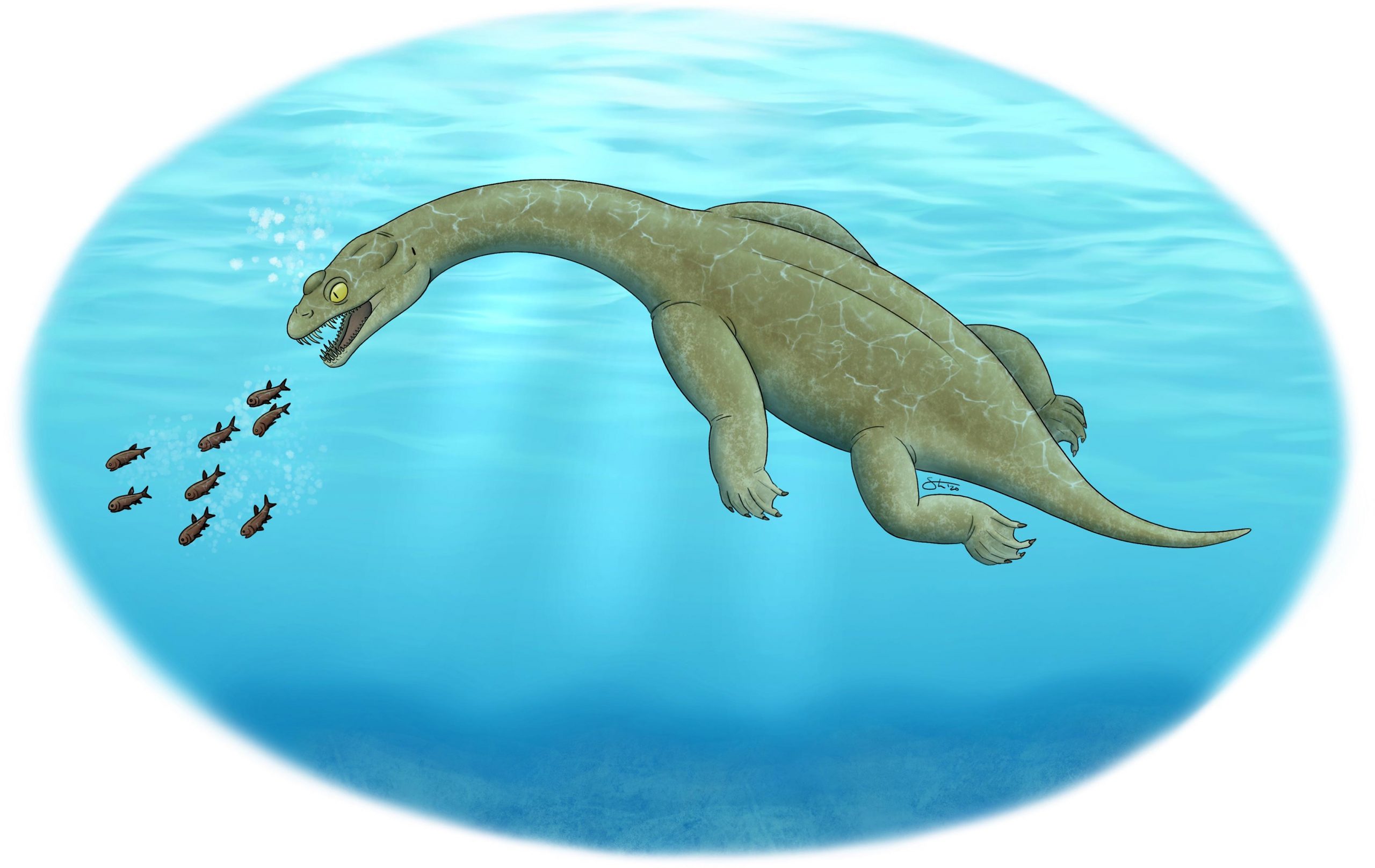

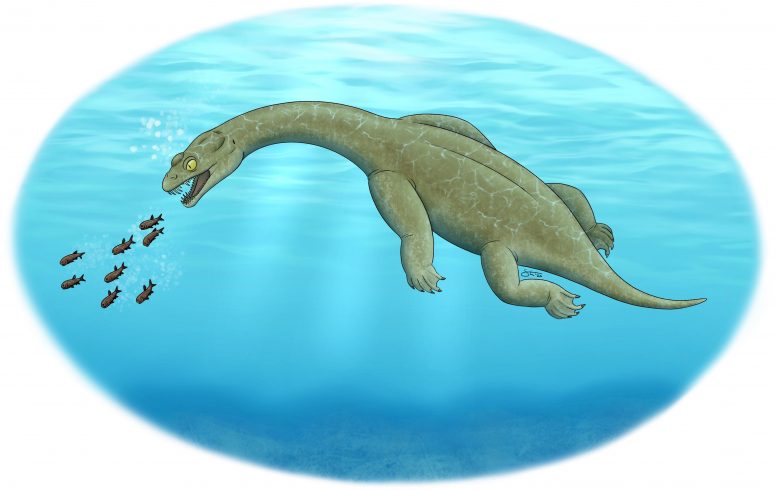

An illustration of Brevicaudosaurus. Credit: Illustration by Tyler Stone BA ’19, Art and Film; https://tylerstoneart.wordpress.com

About 240 million years ago, when reptiles ruled the ocean, a small lizard-like predator floated near the bottom of the edges in shallow water, gathering prey with fang-like teeth. A short, flat tail, used for balance, helps identify it as a new species, according to research published in Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Paleontologists from the Chinese Academy of Scientists and the Canadian Museum of Nature analyzed two skeletons from a thin layer of limestone in two quarries in southwestern China. They identified the skeletons as non-dinosaurs, Triassic marine reptiles with small heads, fangs, fin-like limbs, long necks and normally an even longer tail, probably used for propulsion. However, in the new species, the tail is short and flat.

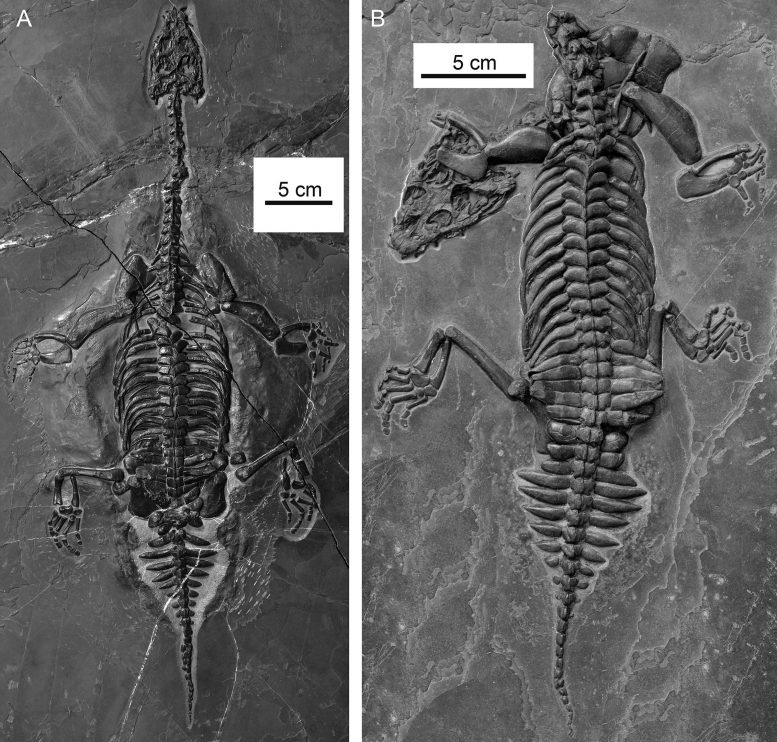

Brevicaudosaurus jiyangshanensis, gen. et sp. nov., skeletons in dorsal view. A, IVPP V 18625, holotype; B, IVPP V 26010, remade example. Credit: Qing-Hua Shang, Xiao-Chun Wu and Chun, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology

“Our analysis of two well-preserved skeletons reveals a reptile with a broad, pachiostotic body (denser bone) and a very short, flattened tail. A long tail can be used to move the water, generating thrust, but the new species we identified was probably better suited to staying close to the bottom in a shallow sea, using its short, flattened tail to balance, like a float. submarine, allowing it to conserve energy while searching for prey, “says Dr. Qing-Hua Shang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing.

Scientists have named the new species Brevicaudosaurus jiyangshanensis, from the Latin “short” for “short”, “caudo” for “tail” and from the Greek “sauros” for “lizard”. The more complete skeleton of the two was found in the Jiyangshan quarry, giving the specimen the name of the species. It is just under 60 cm long.

The skeleton provides further clues to his lifestyle. The forelimbs are more developed than the hind limbs, suggesting that they played a role in helping the reptile swim. However, the bones in the front legs are short compared to other species, limiting the power with which it could pull through water. Most of its bones, including vertebrae and ribs, are thick and dense, further contributing to the reptile’s stocky and sturdy appearance and limiting its ability to swim quickly but increasing stability underwater.

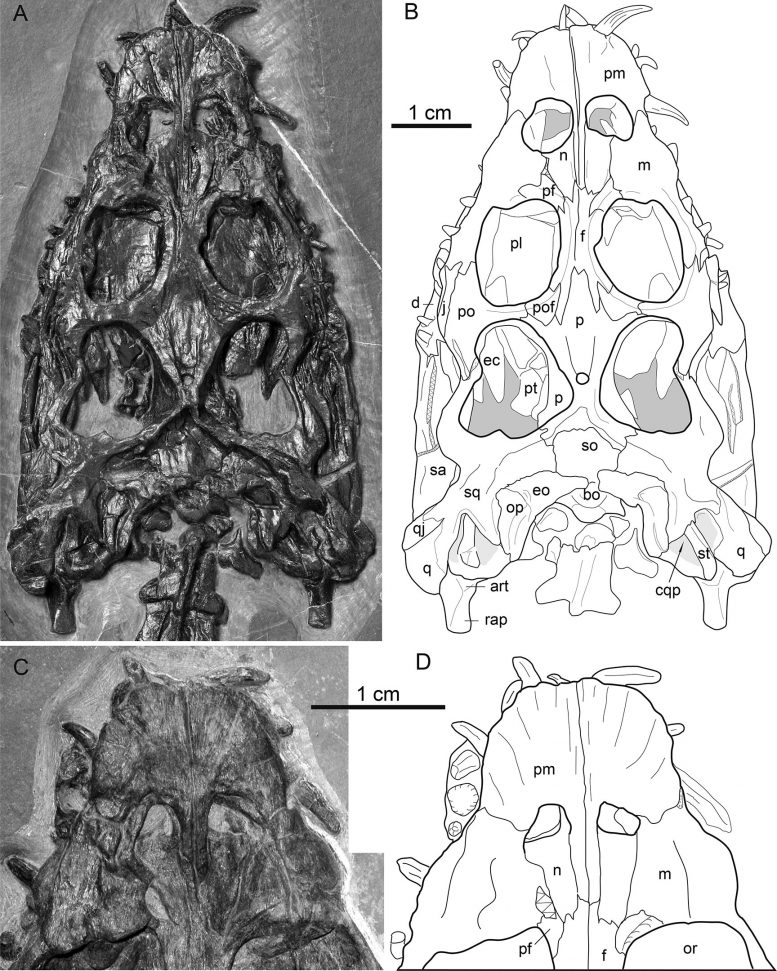

Brevicaudosaurus jiyangshanensis, gen. et sp. nov., IVPP V 18625, photographs and outlines of the skull and mandible in dorsal view. A, B, IVPP V 18625, holotype, in dorsal view; C, D, IVPP V 26010, reported specimen, portion of the muzzle of the skull. The zigzag lines indicate broken areas. Abbreviations: art, articular; bo, basioccipital; cqp, square skull passage; d, dental; ec, ectopterygoid; eo, esoccipital; f, front; j, jugal; m, jaw; n, nasal; op, opisthotic; o, orbit; p, parietal; mp, prefrontal; pl, palatine; pm, premaxillary; po, postorbital; pof, postfrontal; pt, pterygoid; q, square; qj, quadrojugal; rap, retroarticular process; sa, surangular; hence, supraoccipital; sq, squamosal; st, paper clips. Credit: Qing-Hua Shang, Xiao-Chun Wu and Chun, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology

However, the thick, high-mass bones act as ballast. What the reptile has lost in speed, it has gained in stability. The dense bones, known as pachiostoses, may have made them float neutrally in shallow water. Together with the flat tail, this would have helped the predator float motionless underwater, requiring little energy to stay horizontal. Neutral buoyancy should also have allowed it to walk on the seabed in search of slow-moving prey.

Very dense ribs may also suggest that the reptile had large lungs. As suggested by the lack of solid body weight support, the dinosaurs weren’t ocean nuts they needed to come to the surface for oxygen. They have nostrils on the snout through which they breathed. The large lungs would have increased the time the species could spend underwater.

The new species features a rod-shaped bone in the middle ear called the stirrup, which is used for sound transmission. The stirrup was generally lost in other nothosaurs or marine reptiles during storage. Scientists had predicted that if a stirrup were found in a non-dinosaur, it would be as thin and thin as in other species of this branch of the reptile family tree. However, in B. jiyangshanensis it is thick and elongated, suggesting that he had good hearing underwater.

“Perhaps this small, slow-swimming marine reptile had to be alert to large predators as it floated in the shallows, as well as being a predator itself,” says co-author Dr. Xiao-Chun Wu of the Canadian Museum of Nature.

Reference: 28 October 2020, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

DOI: 10.1080 / 02724634.2020.1789651

[ad_2]

Source link