[ad_1]

I’m a clinical trial fanatic. I keep hearing people talk about the seven to ten years it takes to make a vaccine and how dangerous it can be to accelerate this process. The word that keeps appearing is “rushed” and makes the average person nervous about the safety of the vaccine. So, as a clinical trials doctor, I’ll tell you what I do for most of these ten years – and that’s not much.

I am not lazy. I submit grants, have them turned down, re-submit them, wait for the review, re-submit them somewhere else, sometimes in a cycle of doom. When I’m lucky enough to get trial funding, I spend months submitting to ethics boards. I wait for the regulators, deal with personnel changes at the drug company and a “change of lens” away from my tests, and ultimately, if I’m very lucky, I spend my time organizing tests: finding sites, sites of training, panicked because recruitment is scarce, find more sites. I usually have more regulatory problems, and finally, if my big pot of luck doesn’t run out, I may have viable therapy – or not.

At this point, it may experience delays due to profitability issues or other obstacles. I don’t even intend to enter the years normally needed to complete the “preclinical” studies, those before the human trials.

Ten years to develop a vaccine is a bad thing

So the next time someone expresses concern about the astonishing speed with which vaccine tests have taken place, point out that ten years is not a good thing, it is a bad thing. It’s not ten years because it’s safe, it’s ten tough years of fighting indifference, commercial imperatives, luck and bureaucracy. It represents barriers in the process that we have now proven to be “easy” to overcome. You just need unlimited money, some smart and highly motivated people, all the testing infrastructure in the world, an almost unlimited pool of selfless and wonderful volunteers, and some reasonable regulators.

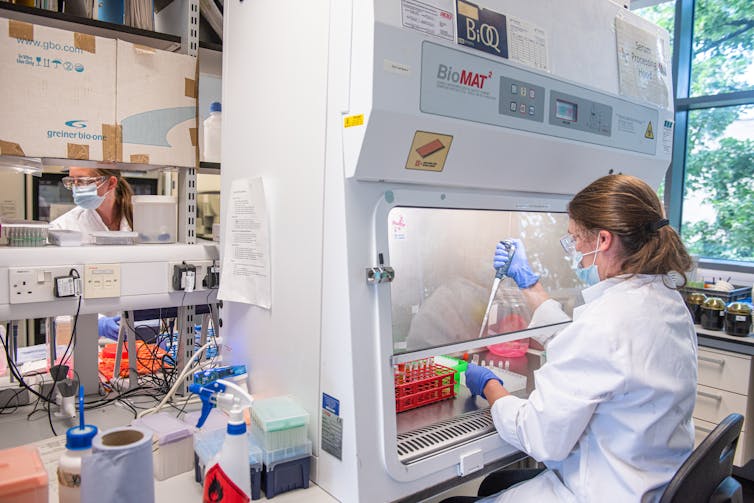

University of Oxford / EPA

With all of this and the ticking of the clock on a global pandemic killing people per second, it turns out we can do amazing things. The vaccine trials have been nothing short of a miracle. A revolution in the way we rehearse that if you think about it maybe it’s not that surprising given our ability to innovate when we really need it.

And we really need – need to be the mother of the invention. Security was not compromised. All studies went through the “steps” or correct process of any normal drug or vaccine. Hundreds of thousands of the best of us volunteered and received an experimental vaccine. The world watched so closely that when only one person got sick, we all discussed it.

To date, there has not been a single associated death related to COVID vaccines and only a handful of potentially serious events. Imagine looking at everyone in a small town for six months and reporting every single heart attack, stroke, neurological condition, or anything that could be judged serious. How surprising is this? It was a triumph of medical science.

I didn’t even mention the lucky confluence of timing which meant that all of this happened at a time when sequencing all the genes in a person or virus is so normal that no one blinks. This supercharged the first preclinical science needed as the cornerstone of several new technologies at the right point to exploit.

Right now, three vaccines have already broken the cover and have shown efficacy beyond what we had ever hoped for. The level was set by the regulators at around 50%. Both Moderna and Pfizer reported 95% effectiveness, and the University of Oxford reported 90% effectiveness for a particular dosing regimen. Safety data has yet to follow, but the vaccine track record is excellent and I am optimistic.

None of this to minimize the challenges still to be faced. It also does not mean that vaccines are free of unanswered safety questions. However, it was a triumph of a good process and great people. I am confident that when regulators carefully review safety and efficacy data, closely followed by every interested scientist in the world, vaccines will only be used if their benefits clearly outweigh the risks – and you should be confident too.

Source link