[ad_1]

UUnless you spent your summers packing Jaffa Cakes in boxes in the 1970s, you are unlikely to have heard of the United Biscuits Network (UBN). It was a radio station for biscuit makers, broadcasting 24/7 to factories in London, Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow. Part industrial psychology, part community radio, UBN was intended to make life in the factory more bearable, but over the course of its nine years of life, it has emerged as one of the boldest, most anarchic and pioneering stations to hit the airwaves. of the United Kingdom.

Music has long been a point of contention in the workplace. Prof Marek Korczynski, co-author of Rhythms of Labor (2013), describes the history of British working life as “a battle over soundscapes”. The bosses initially wanted quiet factories, but during World War II, Korczynski says, “industrial psychologists – the forerunners of human resources departments – started watching cheerful music play in factories at times of day when productivity dropped.” . After the war, as Britain rebuilt itself, this strategy was maintained with muzak: harmless background melodies, played to ease the monotony of factory work.

There was a problem, according to Korczynski: “The workers have grown to hate muzak.” As jobs on the production line were canceled and made more and more monotonous, muzak’s effectiveness weakened and staff turnover soared. For Sir Hector Laing, president of United Biscuits in the 1960s, stemming the flow – and its cost – was desperately needed. Drawing on the success of commercial pirate stations such as Radio Caroline, Laing released Melody Maker, purchased state-of-the-art broadcasting equipment, and created his own station from UB’s headquarters in Osterley, west London (where Sky’s headquarters are today) .

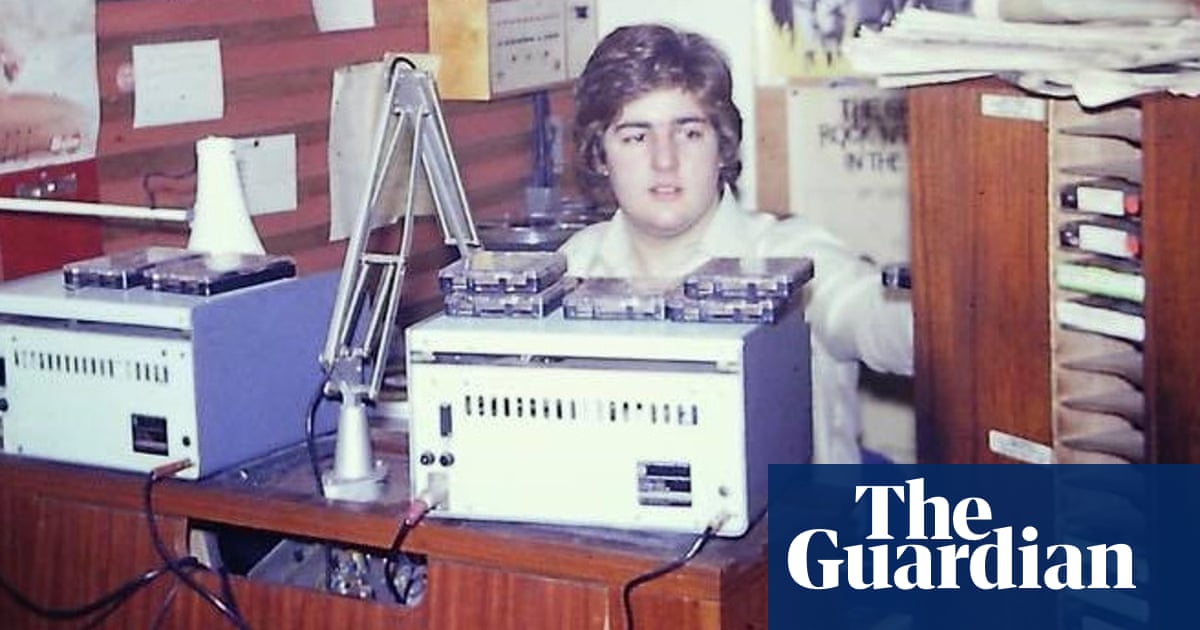

From the beginning, UBN has offered a unique opportunity for novice DJs. It was a 24 hour operation (a British first), well stocked and it wasn’t the BBC. As such, it has become the perfect stepping stone from the pub, club and hospital DJ circuit to the big radio leagues. Graham Dene, which aired on opening day of September 1, 1970, couldn’t believe his luck. “It was like a radio university. We had the best kit, the right studies. We also recorded some jingles from the Radio London pirate ship. It was like the seventh heaven: our own station. “

Laing hired an old pirate ship veteran, Neil Spence, to lead his crew of newcomers as they learned the trade. Giles Squire, who was only 16 when he started UBN, remembers how quickly you had to adjust to the new kit. “We had a saying,” he says, “” Three seconds of silence gets you fired! “After more time, the microphones started looking for noise and the whole factory would hear static!”

The shows were tight and music-oriented, with guests left free provided they didn’t take liberties. Another up-and-coming DJ, Nicky Horne, found out about this five weeks after his graveyard shift began. “Every five songs or so,” he says, “we had to play a Hindi track for Indian workers, and I thought, ‘Sod it, it’s 3am, I’ll play Led Zeppelin instead.’ Almost immediately, Spence called me on the air to put me in my place! “

The songs in Hindi were in constant rotation at all hours of the day, but this brought its own challenges, as Pete Reeves, UBN’s first man on the air, discovered. “We used to play vinyls straight from Bollywood soundtracks, leaving in the chatter thinking it was part of the song. After a while, someone in the shop pointed out to me that we were actually running advertisements for the soap powder that came with the vinyl. “

Growing difficulties aside, UBN has been a runaway success, expanding from the company’s Osterley and Harlesden plants to its bases in the north of England and Scotland. “When we joined,” Squire says, “we were told that if we could take 20% off staff turnover, we would more than pay for ourselves. Within the first year, we got a discount on staff turnover. 40% “.

Despite being something of a national broadcaster, UBN also played the role of local radio, with factory-specific shows playing different music (more country and western in Liverpool, for example) and briefing staff on donation initiatives by blood in their area. His constant presence made mini-celebrities out of DJs, who regularly visited factories and interviewed staff to fill those regional hours. Tony Gillham, who joined UBN in 1975, made his first trip to the Manchester factory while being accompanied by another of the station’s on-air talent, Dale Winton. “We were having dinner at our hotel in the city center when suddenly a crowd of young women – all from the factory – spotted us and rushed to the window. Dale said, “They must be for you!” “

The DJs felt part of a separate entity, but they also made friends in the workshop, participated in charity football tournaments, and even hosted Miss United Biscuits contests. There weren’t many directives from the bosses, but the station was asked to advertise on safety, something they took with ease.

Each week, each guest recorded a new safety sketch, with total freedom to take it wherever they wanted. Some took the form of parody songs, such as the cover of Winton by Shame, Shame, Shame by Shirley & Company, whose refrain became: “Shoes, shoes, shoes / Safety shoes”. Others were more surreal, like a 1973 sketch in which a Scottish Macbethian father whips his daughter’s hands for not cleaning them thoroughly enough. “That was our tone,” says Geoff Allen, who worked at UBN from 1973 to 1975. “We were suggestive and playful, without exaggerating. Even though we probably couldn’t get away with it today!”

By the time UBN aired on December 16, 1979, the world of broadcasting and industry had changed immeasurably. Operation of a station was no longer deemed necessary with the explosion of independent local radios across Britain; an explosion that, ironically, was caused by an excess of former UBN members, from Graham Dene and Nicky Horne on Capital Radio, to Giles Squire on Metro Radio. Andrew Ellinas, who aired the latest hour of UBN, is emphatic about the station’s impact. “UBN was the beginning of the golden age of radio,” says Ellinas. “His legacy resides in every trading post in the UK.”

With the loss of UBN, life at the United Biscuits plant also changed. “Those communities in the workshop have been destroyed,” Korczynski says. “People wore ghetto blasters and played whatever they wanted, when they wanted, for their little section or just for themselves.” This atomization is part of the reason why UBN cannot be replicated today; another reason, as Dene observes, is that factories today are emptier and quieter places. “I went again for one of UB’s anniversaries a few years ago, and I couldn’t believe it: there was no one there!”

Fifty years later, UBN inspires a particular kind of affection in its old staff. Even with people who have worked at the station at different times and met later, mentioning the old cookie factories is like a secret handshake. Some of his alumni lobbied the Radio Academy to acknowledge how pioneering UBN was. “If you had given us an antenna, we would have given Radio 1 a run for its money,” says Dene. “It was so good.”

.

[ad_2]

Source link