[ad_1]

[ad_1]

In the letter

- American artist, programmer, and writer Xiaowei Wang ventured into the remotest regions of China to explore the impact of the technological revolution.

- A blockchain-enabled remote chicken farm embodied the challenges and opportunities transforming China’s economic landscape.

- The ongoing change is unprecedented in scope and comes at a time when food safety concerns are paramount.

when Xiaowei Wang they embarked on the winding journey to the mountain village of Guizhou to visit China’s most advanced chicken farm, they didn’t know what to expect.

Born in China, Wang emigrated to the United States as a child and forged a career as an artist, programmer and writer, as well as creative director of Logic magazine. In common with many Chinese, Wang, who prefers to be called by the pronoun “they”, continued to visit their ancestral home and other Chinese villages.

Recently, they said Decrypt of what turned out to be a rather embarrassing visit, but which rightly demonstrates the incongruous nature of the technological boom that has torn the Chinese countryside apart.

The episode is now the title of a book, “Blockchain Chicken Farm: and other tech stories in the Chinese countryside, “Published last month by FSG Originals and featured in a variety of publications, from New York Times to the Guardian is Huck.

Not just another book on the blockchain

Blockchain may be front and center in the title, but Wang’s book isn’t specifically about the blockchain. Rather, it is a kind of disquisition about how technology, in general, is transforming rural China at lightning speed, and not always for good.

China’s countryside is densely populated terrain, filled with government-funded and large-scale e-commerce startups, data centers and small-scale manufacturing, Wang writes. It is in stark contrast to the misconception that the technological revolution is found exclusively in urban China.

A tableau of situations, sketches and even recipes, Blockchain Chicken Farm conveys the shock of recent transformations juxtaposed with an ancient lifestyle and the hacker culture that is emerging as people modify technology to meet their own needs.

Blockchain chicken farm

One of the central technologies in this rural revitalization is the blockchain; following a number of food safety concerns, it helps build trust in food supply chains. This means that compared to most US urbanites, Chinese urbanites are blockchain and cryptocurrency experts, and the government pushes to promote the former, but not the latter, Wang said.

The campaign, on the other hand, is a different proposal. “There is a big distinction between those who live in large cities and in rural areas,” they said. “Life in the countryside against a Chinese city: it’s like night and day.”

China has one of the highest rates of income inequality in the world, thanks to the income gap between rural and urban areas. As a result, the foray of Chinese mega-companies like Alibaba, JD.Com and NetEase in the food space was well received. The tech giants have been busy centralizing manufacturing and shipping, aided by AI, computing, blockchain, and sensors. They aim to optimize agricultural production, as well as provide worried and wealthy urban consumers with the data they now demand about where their food comes from, at a price.

Wang was interested in how it unfolded on the ground, so they embarked on the long and arduous journey to remote and economically disadvantaged Guizhou. There they visited a farm that supplied poultry for “GoGoChicken”, a partnership between the local government and Shanghai-based Lianmo Technology, which develops technology to track the provenance of chickens on a blockchain. These are sold for the princely sum of 300 RMB ($ 40) on the e-commerce platform JD.Com, with the profits distributed between the farmer and 300 other families in the village.

But their visit did not go entirely according to plan. “County officials [were] I’m really excited to show me how modern their village is, how state of the art it really is, ”Wang said, describing free-range chickens pecking at chosen feeds, wearing what looked like embossed FitBits with QR codes.

The bracelets have tracked the chickens’ moves and position, with instantly viewable data, which customers access via the QR code after being slaughtered (they can even see the photograph of their chicken). These new era chickens are ambassadors of a number of infrastructures, including a proprietary blockchain called Anlink, which demonstrates the latest in supply chain technology.

But then it all got a little awkward. “It was actually a really awkward visit… once I started asking people, ‘well, what do you think of blockchain’, they’re like, ‘why? What are you talking about?’ They thought I was making fun of them, “Wang recalls.

The farmer told them he ended up selling 6,000 chickens through the project. His son, who had recently returned from the city and was now employed by the local government, had been responsible for putting it together.

It seemed like the perfect solution to their problems: lack of a reliable market, low profit margins, and buyers who had a hard time believing the chickens were free-range and worth the asking price. But the future was still uncertain; there had been no repeat orders from Lianmo for 6,000 chickens the following year, nor assistance in dealing with the complex infrastructure involved in running the blockchain chicken farm. Meanwhile, the farmer’s overheads had risen to account for all the technology.

Wang later discovered that Lianmo and the other companies involved in the project had abandoned Guizho because it was simply too remote, but the pattern continued elsewhere.

“There are actually a lot of these small tech companies in China that are doing all sorts of small, piecemeal, fascinating projects,” they said. “It’s amazing how easy it is to start a small startup in China.”

Technology flourishes in remote rural China

It is the bigger companies that are making more waves, with initiatives such as “Taobao villages”, a craft industry created by the Chinese giant Alibaba and named after its phenomenally successful e-commerce site, which caters to both consumers than to small traders. It serves 600 million users, making the likes of Amazon go pale.

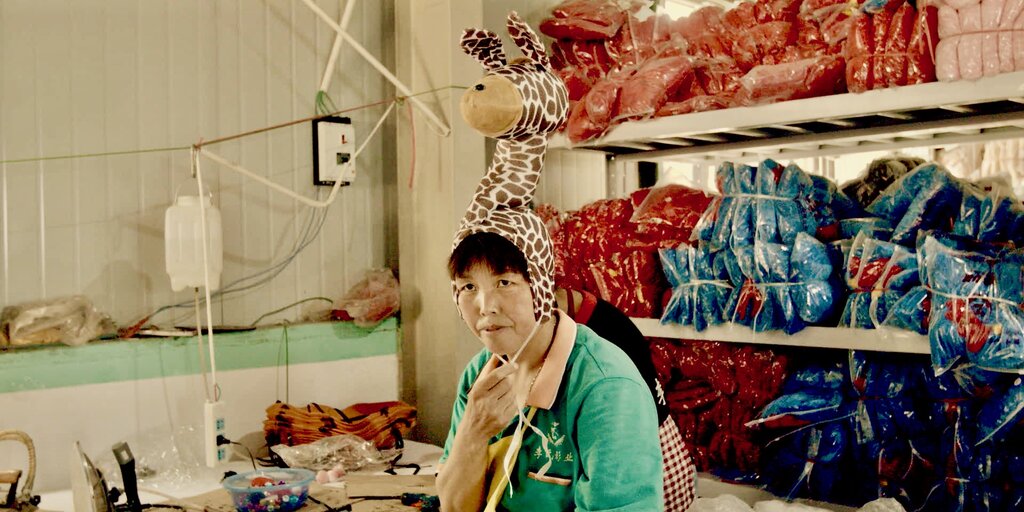

Since the program began in 2012, some 3,000 villages have had their local economies almost completely displaced by companies that serve Taobao and now produce everything from Snow White masquerade costumes to electronic equipment. Even the furthest farmer now knows how to use WeChat for cash transactions, Wang said.

Netease, one of the largest internet gaming companies in the world, Alibaba and others, are making big forays into agriculture as well. The situation in China is complicated. Supply 22% of the world population on just 10% of the world’s arable land it is simply difficult and puts enormous pressure on farmers.

“Blockchain Chicken Farm” describes how large companies aim to optimize agricultural production; they want to combine it with “Internet thinking” and are intent on perfecting the art of raising perfect pigs, one of the largest industries in the country.

The data is fed into Alibaba’s “agricultural brain ET” and the AI provides optimal food, exercise and even music to keep these sensitive creatures from being stressed.

But the miracle of pork in China comes at a price; risks homogenizing pigs and some breeds could die, writes Wang.

The scene from the ground, as “Blockchain Chicken Farm” wants to demonstrate, is increasingly blurred. Blockchain, for example, risks creating more inequality by making food a commodity rather than a fundamental human right, Wang warns. There is a need for incentive structures other than producing the best at the lowest price and a way to counter what could be interpreted as another type of colonialism, “because technical systems are readable only by a select few,” they explained.

Wang believes that whether or not the technology thrives in China will ultimately depend on whether people trust blockchain more than the government, and part of that depends on the community’s ability to expand and diversify.

The “culture of hustle and bustle”

China’s rural revitalization is served by incredible new infrastructure, and entrepreneurs are encouraged to return to their rural homes after years of struggles in Chinese cities. In one small village alone, Wang was told that over 500 young people had returned in the past year.

These young transplants have helped spark a “culture of chaos” in remote rural regions, where Chinese authoritarianism exists alongside a less well-defined local government; where counterfeits replace luxury goods, which are in short supply and where the game of the system according to one’s needs is common (these practices are collectively known as shanzhai, and the name literally means “mountain stronghold”.)

“[The] amount of creativity or type of unintended use [of technology] it’s really fascinating to watch, and it actually gives me a lot of hope, ”Wang said.