[ad_1]

Both of Andrew Kiselica’s grandparents developed dementia when he was in graduate school. While Kiselica was undergoing training in neuropsychology at graduate school, she saw her mother’s father become unable to walk or speak due to severe dementia. The University of Missouri researcher said personal experience motivated her work to identify and prevent neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

Now an assistant professor of health psychology, Kiselica recently concluded a study that led to procedures to define the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease. As there are no current treatments to reverse the course of Alzheimer’s, this discovery may help drug developers identify who could benefit from future Alzheimer’s treatment before symptoms of cognitive decline begin to manifest.

Most families have had this experience of watching someone who is vibrant and full of life essentially transform into someone they can barely recognize. I don’t want people to have to go through it as the last stage of life. The experience with my grandparents was the driving force behind my desire to study this disease “.

Andrew Kiselica, Assistant Professor, School of Health Professions

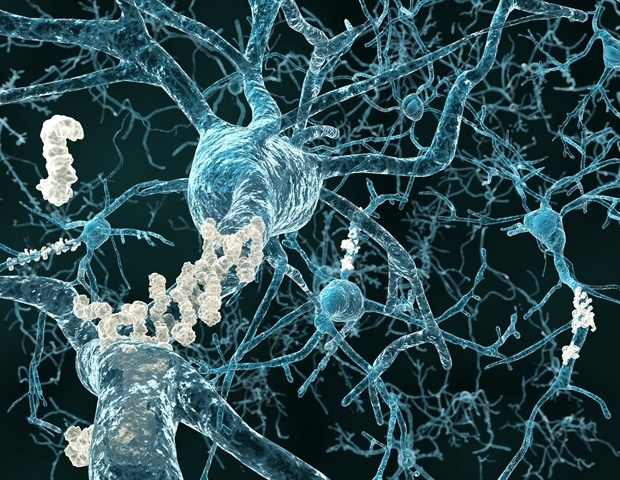

Defined by cognitive changes that affect the ability to complete basic activities in daily life, dementia is most commonly caused by Alzheimer’s disease, a brain disorder in which a buildup of amyloid plaque in the brain leads to memory loss and others. cognitive problems.

Analyzing datasets from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, Kiselica examined more than 400 individuals who had been declared “cognitively normal” and specifically focused on 101 of these individuals who had amyloid plaque buildup in the brain associated with the Alzheimer’s.

After analyzing test results that provided data on their memory and attention, caregiver observations of signs of cognitive decline, and neurobehavioral symptoms such as anxiety and depression, Kiselica found that those with amyloid plaque in their brains were more likely to show Alzheimer’s-related symptoms compared to those without amyloid plaque, as expected. More significantly, Kiselica found that 42% of those with amyloid plaque showed no signs of cognitive decline.

“We have developed clear procedures for classifying individuals who are asymptomatic or symptomatic in the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease,” Kiselica said. “This is important because if a drug to treat Alzheimer’s is approved by the FDA down the road, the drug will likely be more effective on those with Alzheimer’s-related brain changes, but still no external signs of cognitive decline.”

Kiselica added that if those with Alzheimer’s-related brain pathology and outward signs of cognitive decline take a proposed Alzheimer’s drug in the future, it’s possible it will be ineffective because the disease won’t be able to reverse course once the symptoms begin to manifest. Therefore, his research can help developers of future drugs designed to treat Alzheimer’s disease or dementia know what kinds of people to include in their clinical trials.

“This is one of the first studies to demonstrate procedures for defining people in the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease who do and do not show signs of cognitive and behavioral changes,” Kiselica said. “I hope that somehow my research can lead to improving the quality of life of people suffering from neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s.”

Source:

University of Missouri-Columbia

Journal reference:

Kiselica, AM, et al. (2020) An Initial Empirical Operationalization of the Earliest Stages of the Alzheimer’s Continuum. Alzheimer’s disease and associated disorders. doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0000000000000408.

.

[ad_2]

Source link