[ad_1]

His life was a constant of victories and defeats, of deaths and resurrections in which a soccer ball was always at his side. That is why on the day of his farewell to the courts he said: “The ball is not stained.

It will be necessary to remember him in the center of the pitch of the La Boca stadium on November 10, 2001, in tears, the day of his official farewell to football, repeating over and over again that “the ball does not stain”, admitting that If someone has been injured by his drug addiction, it was him, and between one pause and the next, looking into the distance, the stalls crowded with people who, too, shouted and sang “Maradoooooooo, Maradoooooooooo”. We will have to remember him a few years earlier, just before the 1986 World Cup began in Mexico, when he started talking to the players of Italy and Brazil, and with some of his teammates in Argentina, to make them rebel against FIFA and they will change the schedules of the leave, because at 12, or one, with that sun, pollution and altitude, they would die.

In 1986 Maradona was renamed D10S. “Never has a player been as influential in a single World Cup as Maradona in that Cup,” said one of his final rivals, Lottar Mathaus, over time. From the first to the last match, against Germany, Diego Maradona made the impossible possible, up to forcing Joao Havelange, FIFA president, to shake his hand and hand him the World Cup in the main box of the Azteca stadium, swallowing his words and his insults, because days before, before the Argentine attempted the rebellion, he had called him “cursed little black head”. That day, on the afternoon of June 29, Havelange promised revenge and personally took the word for revenge. And he took revenge on that “little black head” who has been proud of being a “little black head” all her life, cutting off his legs once and twice years later.

“They cut off my legs,” Maradona said eight years later in the midst of a chaotic press conference in Boston, US, minutes after Julio Grondona, the president of the Argentine Football Association (AFA), told him that for doping. had come out of the World Cup. Maradona had returned to football and the Argentine team after Colombia’s 5-0 draw at the River Plate stadium. He lost 15 to 20 pounds. He trained day and night and returned to save his team in a play-off against Australia and, later, in the 1994 World Cup. But one day he ran out of prescribed pills and his physical trainer bought them for him. others, with the same compound, but with one more component: ephedrine and ephedrine was one of the thousands of prohibited substances.

They cut off his legs, as they had cut them three years earlier, when he was suspended in the Italian League for 18 months, because an examination in a laboratory that only existed to detect his cocaine addiction determined that he had played a game with his team, Napoli, under the influence of drugs. Maradona said coke had nothing to do with football, but it didn’t matter. Someone, or many, and from above, had long ago lowered the hammer to plead guilty to whatever it was. He was guilty of drugs. He was guilty of having beaten Silvio Berlusconi’s Milan, a game that “should not have won”, as he later said. He was guilty of being the captain of Argentina who eliminated Italy at the 1990 World Cup in Naples and left them out of the World Cup. He was guilty of reminding southern Italians that the north had always humiliated them.

He was the culprit of all for facing the power and the powerful. The media that praised him earlier, because to say Maradona meant money, a lot of money, and to say Maradona was to sell copies of newspapers and magazines and raise the rating of whatever program called him, began to crucify him. On April 26, 1991, for example, the Buenos Aires police broke into an apartment he was staying in, in the Caballito neighborhood, and arrested him as a drug addict. When Maradona left the building, with a clouded, lost, glassy look, there were more than a hundred photographers from the various media of the town on the street. “Someone warned them,” he later commented. Similarly, his photo as a “criminal” had already been around the world, and in one place and another people repeated that he was a “drug addict”, an adjective that kept him forever until the end of his days.

Maradona was the enemy to be defeated, the one they had to humiliate. His only weapon was football. The ball. With her, for her, he had mesmerized Argentinos Juniors fans ever since she was a “chive” before her first division debut on 20 October 1976 against Talleres de Córdoba. Years later, many years, some collector of anecdotes and almost invisible stories remembered that when he went to look for the first photo of Maradona’s first comedy in the first division, he found nothing. However, he continued in his research. He went through files and archives, investigated, thought, stitched the points together, until he found the image he so badly needed. A photo assistant had kept it in an ordinary envelope, with a general inscription that said: “Photo Argentinos Juniors-Talleres – October 20, 1976”.

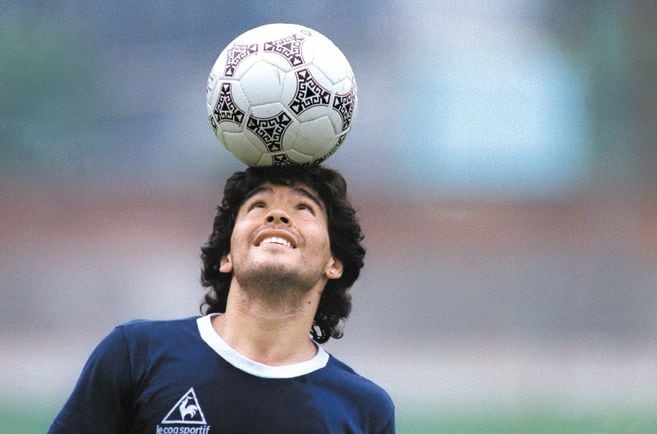

With the same ball of that time, even if it changed color and brand, that worn out and deflated ball that an uncle had given him and with which he slept when he was just two years old, Maradona then dazzled the Boca fans in the 81st century he mesmerized the world, as before and as always, making the impossible possible. And then, in bursts, despite a fracture of the tibia and fibula and hepatitis, he fascinated those of Barcelona, and finally the Neapolitans, who hung flags with his face and his name next to the venerated saint of the city , San Jenaro. Maradona brought Naples and the Neapolitans back to their ancient importance. He put them back on a map not just of football, but of history, and he did it with a ball.

And with a ball he was world champion, and forced Havelange to shake his hand, and took revenge, his revenge, on the British for those killed in the Falklands war with two anthological objectives that reflected his side of humble neighborhood and Soccer D10S . With a ball he laughed, celebrated, sang and cried and said, as in a kind of prayer, “the ball does not stain”.

.

[ad_2]

Source link