[ad_1]

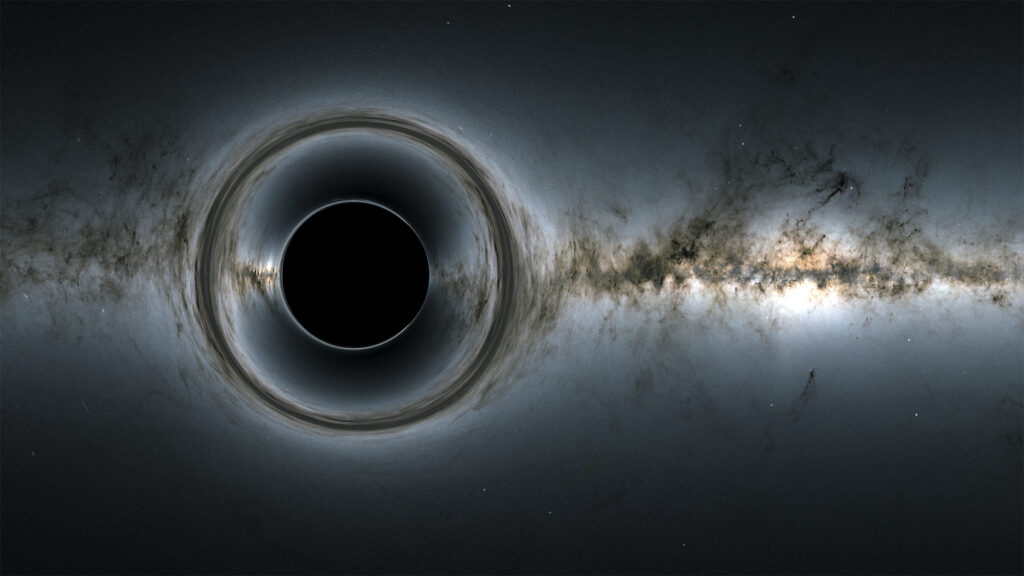

A black hole is an astronomical object with such a strong gravitational force that nothing, not even light, can escape it. The “surface” of a black hole, called the event horizon, defines the limit at which the speed required to avoid it exceeds the speed of light, which is the speed limit in the cosmos. Matter and radiation are trapped and cannot get out.

Two main classes of black holes have been extensively studied. Black holes of stellar mass, three to dozen times the mass of the Sun, are scattered throughout our galaxy, the Milky Way, while supermassive monsters weighing between 100,000 and billions of solar masses are found in the centers of the largest galaxies. , including ours.

For a long time, astronomers have theorized the existence of a third class called intermediate-mass black holes, weighing between 100 and more than 10,000 solar masses.

While a handful of candidates have been identified by indirect evidence, the most concrete example to date was observed on May 21, 2019, when the National Foundation’s Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO). US Science, based in Livingston, Louisiana and Hanford, Washington, has detected gravitational waves from a merger between two stellar-mass black holes. This event, named GW190521, created a black hole that weighed 142 suns.

A stellar-mass black hole forms when a star with more than 20 solar masses runs out of fuel in its core and collapses under its own weight.

The collapse triggers a supernova explosion that ejects the outer layers of the star. But if the shattered core contains more than three times the mass of the Sun, no force will be able to stop its collapse into a black hole. Little is known about the origin of supermassive black holes, but they are known to exist from the earliest days of a galaxy’s life.

Once formed, black holes grow from the accumulation of matter they trap, including gas from nearby stars and even other black holes.

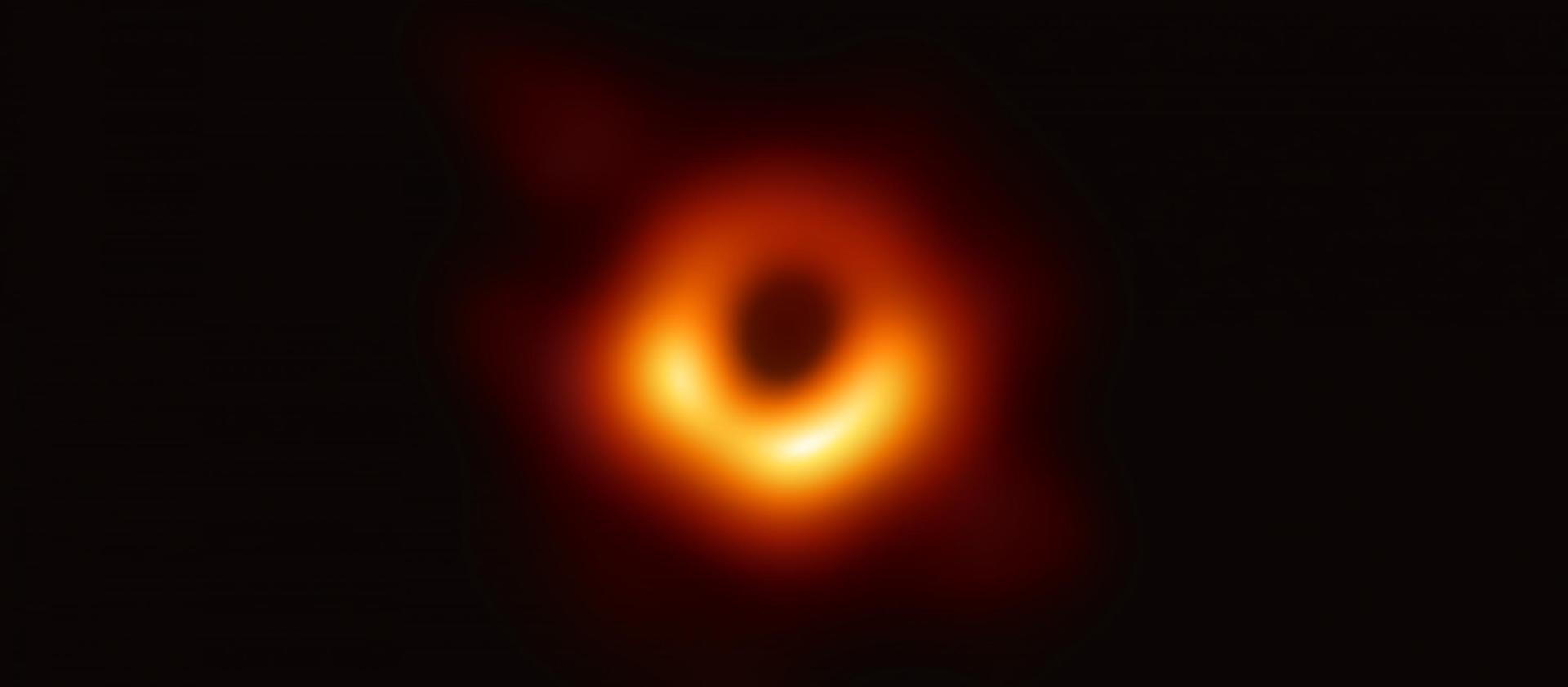

In 2019, astronomers captured the first image of a black hole using the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), in an international collaboration that connected eight ground-based radio telescopes under a single Earth-sized antenna. The supermassive black hole is located in the heart of a galaxy called M87, located about 55 million light years away, and weighs more than 6 billion solar masses. Its event horizon extends so far that it can encompass much of our solar system beyond the planets.

Another important milestone in the study of black holes occurred in 2015, when scientists first detected gravitational waves, the same waves in the fabric of space-time that Albert Einstein had predicted a century earlier, in his general theory of relativity. . LIGO detected ripples from an event that happened 1.3 billion years ago, known as GW150914, in which two black holes spiraled around each other as they merged. Since then and through the study of gravitational waves, LIGO and other structures have observed numerous mergers of black holes.

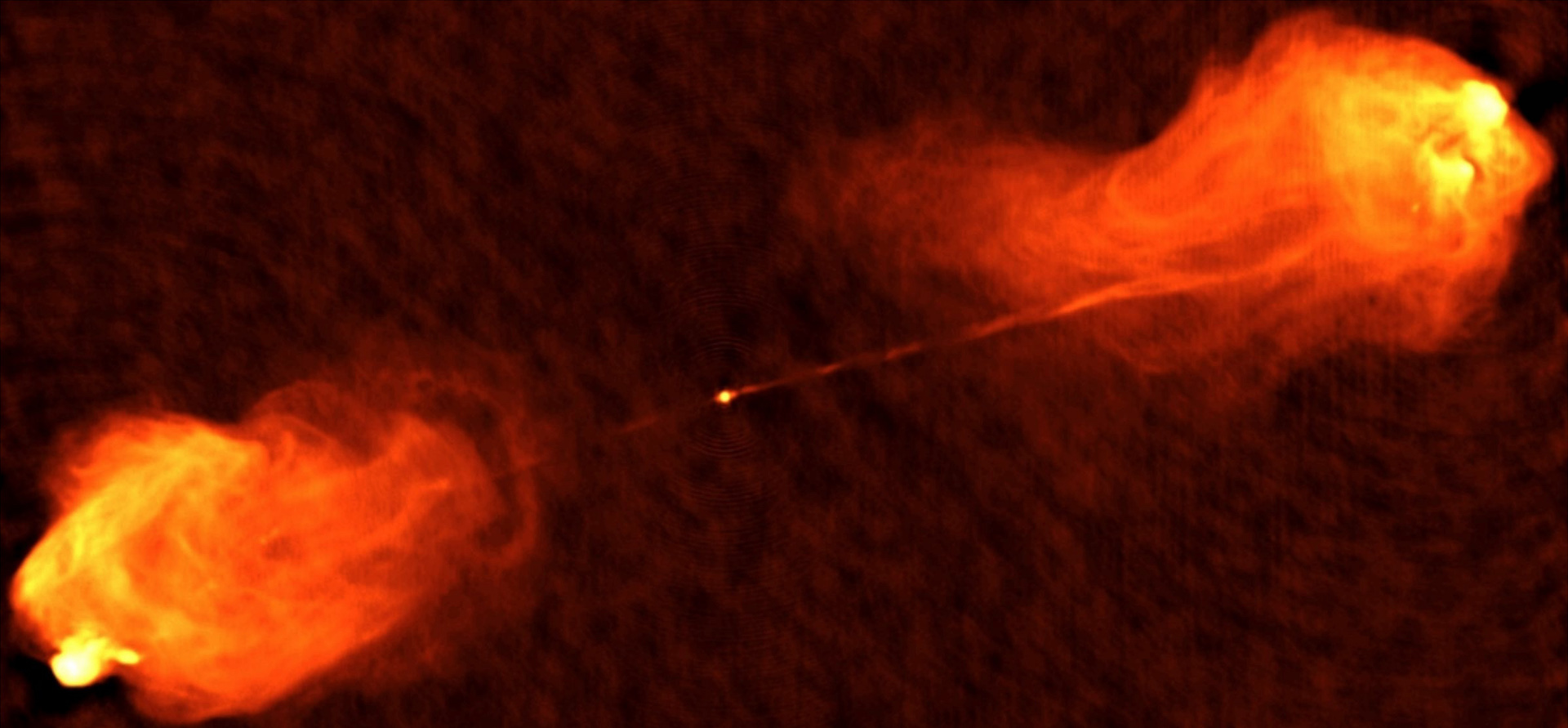

These are new and exciting techniques, however: Astronomers have studied black holes for decades through the various spectra of light they emit. Although light cannot escape a black hole’s event horizon, huge gravitational waves in its vicinity cause nearby matter to heat up millions of degrees and emit radio waves and X-rays. Part of the matter that orbits even more near the event horizon can be released, forming jets of particles that move near the speed of light emitting radio waves, x-rays and gamma rays. The jets of matter from supermassive black holes can span hundreds of thousands of light years.

NASA’s Hubble, Chandra, Swift, NuSTAR and NICER space telescopes, as well as instruments from other missions, continue to observe black holes and their environment so that we can learn more about these enigmatic objects and their role in evolution of black holes. galaxies and the universe.

.

[ad_2]

Source link