[ad_1]

The discovery of a 2-million-year-old skull in a South African cave is changing what we think we know about one of humanity’s primitive ancestors, scientists report in a new study.

But the fossil specimen recently unearthed from the extinct human species Paranthropus robustus it is also offering researchers a unique snapshot of the transformations climate change could unleash in a population living under environmental stress, spurring adaptations that could make life easier and more likely survival.

P. robustus, named for its rugged appearance with a large, sturdy skull, jaw, and teeth, emerged about 2 million years ago in South Africa, and eventually became one of the first hominid species discovered and studied by anthropologists of the mid- 20th century.

However, it seems that this is not all P. robustus the individuals were equally robust, and we know this from the recently unearthed sample identified as DNH 155.

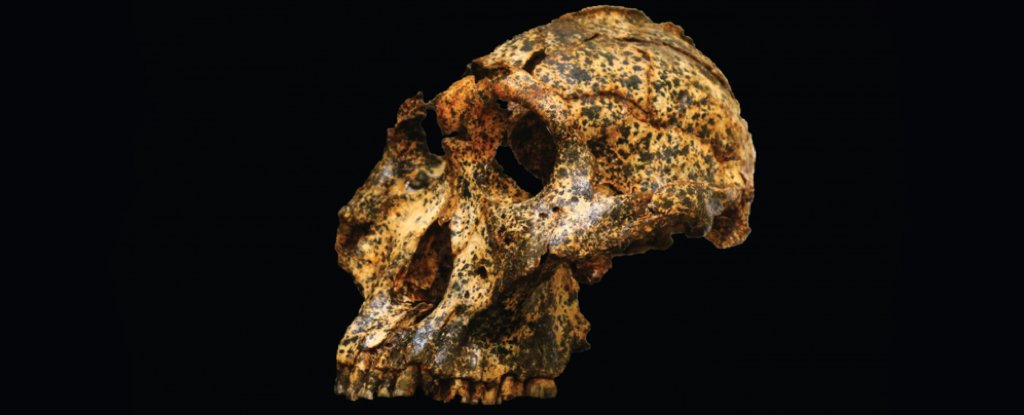

The reconstructed skull of DNH 155. (Jesse Martin and David Strait)

The reconstructed skull of DNH 155. (Jesse Martin and David Strait)

DNH 155, discovered in 2018 by a student during a field expedition into the Drimolen cave system northwest of Johannesburg, appears to be somewhat different from his P. robustus relative, at least based on the fossil evidence uncovered before.

DNH 155, a male, is significantly smaller than the others P. robustus specimens believed to be male, which were recovered from a nearby site called Swartkrans. Indeed, the smaller stature of the DNH 155 more closely resembles a female individual, known as DNH 7, also from the Drimolen quarry site.

But there is more to geography that divides these two ancient populations. There is also the question of time: about 200,000 years, give or take.

“Drimolen predates Swartkrans by about 200,000 years, so we believe it P. robustus it evolved over time, with Drimolen representing an early population and Swartkrans representing a later, more anatomically derived population, ”explains Jesse Martin, co-lead author and PhD candidate in paleoscience, of LaTrobe University in Australia.

In their new study, Martin and his team claim that DNH 155 and DNH 7 provide a glimpse of a primitive state of P. robustus before microevolutionary changes over the next 200 millennia encouraged the adaptations seen in the Swartkrans set.

One of the main factors that could have caused such an event, the researchers think, was an ancient episode of climate change that hit the South African landscape about 2 million years ago, in which the environment became more open, drier and more open. cooler.

Those changes would leave their mark on many things, including the types of foods that were available P. robustus, which need to bite and chew hard vegetation, foods that for DNH 155 and DNH 7 would not have been so easy to nibble and chew, given the arrangement of the teeth and chewing muscles.

“When compared with geologically younger specimens from the nearby Swartkrans site, Drimolen’s skull shows very clearly that it was less suited to eating these demanding menu items,” says Arizona State University evolutionary anthropologist Gary Schwartz.

Despite the successful adaptations they slowly changed P. robustusof the body of about 200,000 years, unfortunately it did not have to be. The species eventually became extinct. Around the same time, our direct ancestor, Standing man, was also emerging in the same part of the world.

“These two very different species, H. erectus with their relatively large brains and small teeth, e P. robustus with their relatively large teeth and small brains, they represent divergent evolutionary experiments, ”says co-author and archaeologist Angeline Leece of LaTrobe University.

“While we were the lineage that ultimately won, the fossil record suggests that P. robustus it was much more common than H. erectus on the landscape 2 million years ago “.

The results are reported in Nature, ecology and evolution.

.

[ad_2]

Source link