[ad_1]

[ad_1]

Several Chinese researchers from Fudan University, Tsinghua University and the University of California Riverside have produced the first systematic study on the extraction of malignant cryptocurrencies, known as cryptojacking, which reveals increasing complexity over time. And it does not seem that this tendency will soon die.

What is Cryptojacking?

Cryptography has established itself in the cybersphere while cryptocurrency industry valuation has increased over the last 18 months and refers to the point where a hacker hijacked the processing power of a computer to extract cryptocurrency on behalf of the hacker. AdGuard reported in November 2017 that over 220 cryptojacking websites were found among the top 100,000 websites according to Alexa. And this trend is not likely to go out soon.

As reported by Bitcoin Magazine in March 2018, the National Cyber Security Center of the U.K. stated that "… it is likely that in 2018-19 one of the main threats will be a new cryptocurrency mining technique that exploits visitors to a website."

The phrase "cryptojacking" exploded on the scene when it was discovered that The Pirate Bay was experimenting with Coinhive in September 2017 to see if the non-profit could generate more revenue through its website. Coinhive allows you to add a script to a web page and extract the Monero cryptocurrency (XMR) using a visitor's processing power.

But the administrators of The Pirate Bay have mistakenly configured the settings to use the full processing power of a visitor without their consent, which led to an explosion of misuse of the Coinhive service. Although altruistic goals can be achieved using in-browser mining, as evidenced by the "Hope Page" of UNICEF, it has been increasingly used for nefarious purposes, with increasing pressures on services such as Coinhive to make it less attractive to cyber criminals.

Hackers can also exploit the weak security measures of a website by releasing scripts in web pages for cryptocurrencies, such as the one that happened with the website of the American television show Showtime in September 2017. A recent research paper has shown that, even if many cases have popped up, cryptojacking could be even more widespread than we think.

Existing identification techniques only scratch the surface

First, the study examines the extent of encryption, which has never been fully measured due to the arbitrary nature of cybersphere detection for this type of malicious attack. The research finds that the existing approaches assume that web page cryptography runs out of user CPU resources or contains keywords such as malignant signatures of payload, and it has been noted that many counterexamples have been discovered.

Pointing to regular hash-based repeat calculations with a cryptographic detector called CMTracker for over 850,000 Web sites, the study was able to provide a more complete picture of what is actually happening and found that 53.9% of the samples identified would not have been discovered by current cryptographic detection approaches based on blacklists, which are both incomplete and inaccurate. Furthermore, the CMTracker results were manually checked.

But how does CMTracker work and how did you find nearly three times as many cryptojacking domains as the latest reports? Two behavior-based profilers are used, one for detecting automatic mining scripts, known as a hash-based profiler, and one for monitoring the calling stack of a website, known as stack-structure profiling. For the hash-based profiler, if a website uses more than 10 percent of hashing time, it is reported as a cryptocurrency miner.

The idea for the stack structure profiler is similar to this: Data mining activities will not take place when the user is loading the page; rather, one or more dedicated threads are created because the mining cryptocurrency is supplied with a heavy workload. If hackers use code obfuscation techniques to circumvent hash-based profiling, then the repeated behavior patterns of the miner's execution stack can be used to identify cryptocurrency miners.

The stack depth and the call chain of the mining scripts are repeated and regular. Looking at whether a dedicated thread repeats the call chain periodically and if the call chain occupies more than 30% of the execution time in this thread, it is reported that a cryptocurrent miner is present. Along with the condition for a hash-based profiler, these two thresholds are the lower limits of cryptojacking in the real world.

The final check is performed manually, examining the terms of service of each website to see if there is a user agreement that clarifies to the user or implicitly in their agreement that their processing power is used for mining cryptocurrency during the visit to the website. The study found that only 35 websites were "benign", with an implicit agreement between users.

In evaluating CMTracker's performance, the researchers chose a subset of 200 websites from the example to manually check whether cryptographic cryptography scripts were actually running on the Web site in question and did not detect false positives. While the document recognizes that some cryptojacking websites have escaped CMTracker, "… neither we nor other publicly available reports have shown any evidence of real cases that could escape the two detectors based on CMTracker behavior."

How Rampant is the Cryptojacking problem?

Of all the top 100,000 sites according to the Alexa rankings, CMTracker detected 868 unique domains containing cryptography and on a further evaluation of external links, including 548,264 domains distinguished by the 100,000 websites classified by Alexa, found a total of 2,700 cryptojacking sites.

Compared to previous reports, the situation is getting worse over time, illustrated by the following study table. The cryptojacking activities observed increased by 260% in just five months from November 2017 to April 2018.

260% increase in cryptojacking observed from November 2017 to April 2018

The websites most affected are those relating to adult content, art and entertainment; this makes sense, since most of the websites in these categories provide pirated sources, so users spend a lot of time searching for a particular movie, episode or video, which translates into greater profits for attackers. The more time is spent on the site, more processing power is committed to cryptocurrency.

Using a basic approximation technique based on the difficulty of extracting Monero, as well as his reward and price, the study estimated that hackers could earn $ 1.7 million from more than 10 million users a month.

In terms of global energy consumption, as the victims of cryptojacking are forced to consume more electricity, it costs more than 278,000 kWh more energy per day, enough energy to power a small American city with about 9,000 people. Using that attached power, the aggressors are supposed to collectively make about $ 59,000 a day.

The main players in the game Cryptojacking

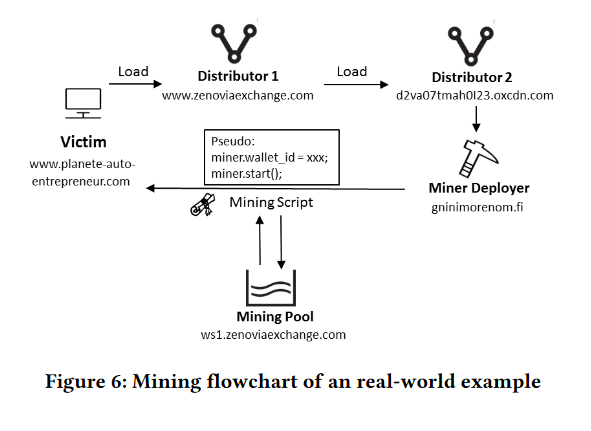

Who is responsible for cryptojacking? The study also investigates the players, and the figure below shows a real example of the interaction between each of these players. Using the distribution of several mining participants from a random subsection of their sample, some answers are provided.

The cryptojacking process displayed and the players involved

Most of the participants' domains occur in no more than three harmful samples, and only a small percentage of mining pools, mining distributors, or miner can be found in more than 10 Web pages. The results suggest that blacklists may be ineffective because the unauthorized miners are not centrally controlled.

Another key result is that advertisers and mining services are mostly connected to cryptojacking websites. For example, it detects a trend for advertisers who turn to malicious mining, citing zenoviaexchange.com, a similar service to Coinhive, as an example of a former advertising service provider who is now a miner.

In addition, by studying the distribution of wallet IDs associated with the mining scripts and discovering that a certain wallet ID is commonly associated with less than three malicious Web pages, the data leads to the conclusion that many different actors benefit from the misuse of cryptocurrency mining.

To better understand the dynamics of cryptojacking, research also sheds light on the life cycle of malicious miners. About 20% of the deployer domains that are cryptographic pages in the sample disappear in less than nine days, but distributors migrate to more recent domains at a lower rate. the study emphasizes that "It is interesting to note that blacklists are not addressed to distributors' domains, even if they rarely change".

Life cycles of cryptojacking domains; miners, distributors and mining tanks

Escaping can also mean something more than just migrating to a new domain. The study finds that, out of 100 cryptojacking sites in the example, there were 56 instances that limited the use of the CPU, 43 cases of concealment of the payload and 26 cases of concealment of the code. For example, a pirated streaming site can use 30 percent CPU for video and only 10 percent CPU for mining, making it difficult to alert the user.

Two examples highlighted in the study illustrate the increasing sophistication of cryptojacking activities. Firstly, cryptojacking can occur through the obfuscation of the code, in which the malicious code is hidden or buried in the code.

Another notable technique used by some cryptojacking domains is the use of two different mining services, such as Coinhive and Crypto-Loot. In the event that one of the mining ministries are blocked by Ad Blockers or turned off, the cryptojacking domain is resistant to any errors in Coinhive or Crypto-Loot, in case one of the two is on the blacklist.

Protection and mitigation measures for Cryptojacking

As cryptojacking participants can use more sophisticated means to circumvent detection, they ask themselves whether browser extensions or antivirus programs can protect users from this type of computer theft. The researchers suggest that most of the protective measures are based on blacklists and then go on to evaluate the effectiveness of two of the most used black lists in a 15-day experiment: NoCoin and MinerBlock.

The results show that less than 51% of malicious attacks are detected and – due to the fact that blacklists are updated every 10 or 20 days, compared to nine or less for data mining deployers – this divergence means that the malicious actors are always take a step forward, as cryptojacking domains migrate or fade at a higher rate. As a result, the detection rate does not increase, even if coverage does.

To effectively combat cryptojacking, researchers propose a behavior-based approach to detection, which can then be implemented by browser extensions and antivirus engines. As indicated by the experiments, the CMTracker takes three seconds to analyze a web page for cryptojacking and, when combined with a white list for those Web sites that explicitly refer to the donation of processing power in the terms of service of the user, could effectively reduce the malicious extraction.

These researchers also point to cryptocurrency mining services that have paid inadequate attention to the misuse of their services; the mining scripts are executed without the user's notification and users can not disable these scripts. As a result, they propose that mining services like Coinhive, which feeds half of all cryptographic domains, must take responsibility. Mining services could do this by implementing a pop-up window or something similar to notify the user, allow them to deny the request and disable the mining process.

At the moment, there is an implementation of Coinhive called AuthedMine which is an opt-in version. As highlighted by Krebs on security in March 2018, it is little used, which Coinhive has attributed to anti-malware companies. "They identify our opt-in version as a threat and block it," Coinhive told Krebs on security. "Why should someone use AuthedMine if it's stuck just like our original implementation?"

Bitcoin Magazine contacted Coinhive via e-mail regarding the research document and if their service will be changed but, at the time of writing, no response has been received.

To facilitate further research on cryptojacking, the research team plans to release the CMTracker source code on GitHub, as well as on the list of cryptojacking websites.

The complete document "How to shoot in the back: a systematic study of Cryptojacking in the real world" can be found here. The document will be presented at the ACM SIGSAC 2018 Conference on Information Security and Communications in Toronto, Canada, to be held from 15 to 19 October 2018.