[ad_1]

Using post mortem tissue samples, a team of researchers from Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin has studied the mechanisms by which the novel coronavirus can reach the brains of COVID-19 patients and how the immune system responds to the virus once it does. The results, which show that SARS-CoV-2 enters the brain via nerve cells in the olfactory mucosa, were published in Nature Neuroscience. For the first time, the researchers were able to produce electron microscopic images of intact coronavirus particles within the olfactory mucosa.

It is now recognized that COVID-19 is not a purely respiratory disease. In addition to having effects on the lungs, SARS-CoV-2 can impact the cardiovascular system, the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system. More than one in three people with COVID-19 report neurological symptoms such as loss or change in smell or taste, headache, fatigue, dizziness, and nausea. In some patients, the disease can also result in stroke or other serious conditions.

Until now, researchers had suspected that these manifestations must be caused by the virus entering and infecting specific cells in the brain. But how does SARS-CoV-2 get there? Under the joint leadership of Dr. Helena Radbruch of the Department of Neuropathology of Charité and the Director of the Department, Prof. Dr. Frank Heppner, a multidisciplinary team of researchers has now tracked how the virus enters the central nervous system and subsequently invades the brain.

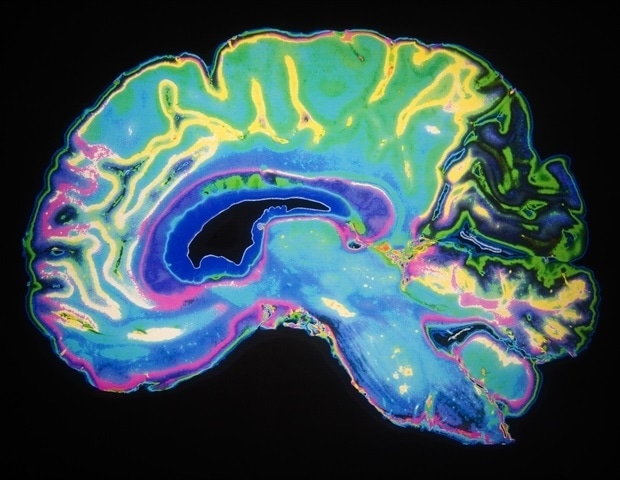

As part of this research, experts from the fields of neuropathology, pathology, forensics, virology and clinical care studied tissue samples from 33 patients (average age 72) who died at the Charité or the Göttingen University Medical Center after contracting COVID -19. Using the latest technology, the researchers analyzed samples taken from the olfactory mucosa of deceased patients and from four different brain regions. Both tissue samples and distinct cells were tested for SARS-CoV-2 genetic material and a “spike protein” found on the surface of the virus.

The team provided evidence of the virus in several neuroanatomical structures that connect the eyes, mouth and nose with the brain stem. The olfactory mucosa revealed the highest viral load. Using special patches of tissue, the researchers were able to produce the first electron microscope images of intact coronavirus particles within the olfactory mucosa. These have been found both within nerve cells and in processes extending from nearby supportive (epithelial) cells. All samples used in this type of image-based analysis must be of the highest possible quality. To ensure this was the case, the researchers ensured that all clinical and pathological processes were closely aligned and supported by a sophisticated infrastructure.

“These data support the idea that SARS-CoV-2 is able to use the olfactory mucosa as a gateway to the brain,” says Prof. Heppner. This is also supported by the close anatomical proximity of the mucosal cells, blood vessels and nerve cells in the area. “Once inside the olfactory mucosa, the virus appears to use neuroanatomical connections, such as the olfactory nerve, to reach the brain,” adds the neuropathologist. “It is important to emphasize, however, that the COVID-19 patients involved in this study presented what would be termed a serious disease, belonging to that small group of patients in which the disease proves fatal. It is not necessarily possible, therefore, to transfer the results of our study in cases with mild or moderate disease “.

How the virus travels from nerve cells remains to be fully elucidated. “Our data suggest that the virus travels from the nerve cell to the nerve cell to reach the brain,” explains Dr. Radbruch. He adds: “It is likely, however, that the virus is also carried through blood vessels, as evidence of the virus has also been found in the blood vessel walls of the brain.” SARS-CoV-2 is far from being the only virus capable of reaching the brain via certain pathways. “Other examples include the herpes simplex virus and the rabies virus,” explains Dr. Radbruch.

The researchers also studied how the immune system responds to SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition to finding evidence of activated immune cells in the brain and olfactory mucosa, they detected the immune signatures of these cells in brain fluid. In some of the cases studied, the researchers also found tissue damage caused by stroke following thromboembolism (i.e. the obstruction of a blood vessel by a blood clot).

“In our eyes, the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the nerve cells of the olfactory mucosa provides a good explanation for the neurological symptoms found in COVID-19 patients, such as loss of smell or taste,” explains Prof. Heppner. . “We also found SARS-CoV-2 in areas of the brain that control vital functions, such as breathing. It cannot be excluded that, in patients with severe COVID-19, the presence of the virus in these areas of the brain will have an exacerbating impact. on respiratory function, which adds to respiratory problems due to SARS-CoV-2 lung infection. Similar problems could arise in relation to cardiovascular function. “

Source:

Charité – Medical University of Berlin

Journal reference:

Meinhardt, J., et al. (2020) Transgingival olfactory invasion of SARS-CoV-2 as a gateway to the central nervous system in individuals with COVID-19. Nature Neuroscience. doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5.

.

[ad_2]

Source link