[ad_1]

(MENAFN – The Conversation) In controlled laboratory situations, face masks appear to do a good job of reducing the spread of coronavirus (at least in hamsters) and other respiratory viruses. However, evidence shows that mask-wearing policies appear to have had much less impact on the spread of COVID-19 in the community.

Why this gap between effectiveness in the laboratory and effectiveness seen in the community? The real world is more complex than a controlled laboratory situation. The right people must wear the right mask, the right way, at the right times and places.

The real-world impact of face masks on virus transmission depends not only on the behavior of the virus, but also on the behavior of the aerosol droplets in different contexts and on the behavior of people themselves.

We carried out a comprehensive review of the evidence on how face masks and other physical interventions affect the spread of respiratory viruses. Based on the current evidence, we believe the impact on the community is modest and it may be best to focus on using the mask in high-risk situations.

Read more: How a 150-year experiment with a beam of light showed that germs exist and that a face mask can help filter them

Proof

Simply comparing infection rates in people who wear masks with those who don’t can be misleading. One problem is that people who don’t wear masks are more likely to go to crowded spaces and less likely to socially distance themselves. People most concerned often adhere to different protective behaviors – they are likely to avoid crowds and social distances as well as wearing masks.

This correlation between mask wearing and other protective behaviors could explain why studies comparing mask wearers to non-mask wearers (known as “observational studies”) show greater effects than those seen in trials. Part of the effect is due to these other behaviors.

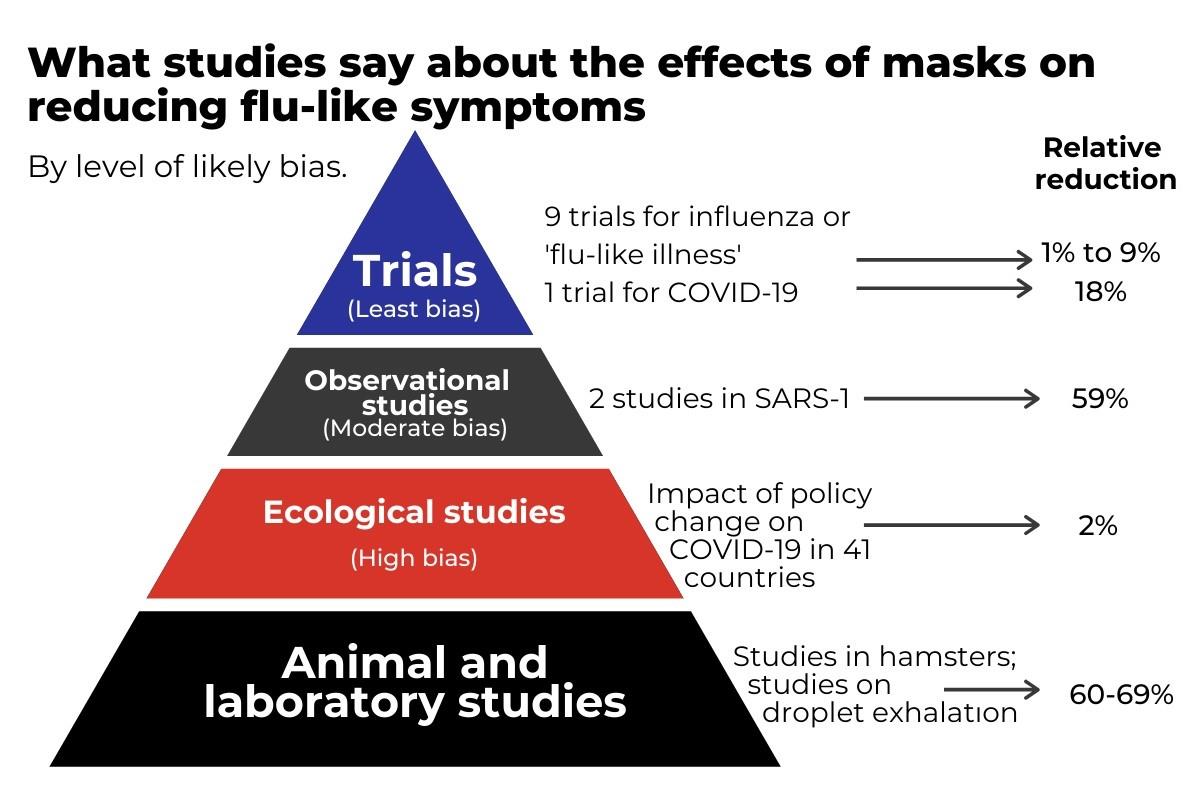

The most rigorous, but difficult, way to evaluate the effectiveness of masks is to take a large group of people and ask some to wear them and others not, in a so-called controlled process. We found that nine such studies were conducted for flu-like illnesses. Surprisingly, when combined, these studies found only a 1% reduction in flu-like illness among mask wearers versus non-wearers and a 9% reduction in laboratory-confirmed influenza. These small reductions are not statistically significant and are most likely due to chance.

Read more: 13 helpful tips on how to wear a mask without your glasses fogging, out of breath, or sore ears

None of these studies have studied COVID-19, so we can’t be sure how relevant they are to the pandemic. The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is similar in size to the flu, but has a different ability to infect people, so it’s possible that masks may be more or less effective for COVID-19. A recently published study in Denmark of 4,862 adults found that SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred in 42 randomized participants to masks (1.8%) compared with 53 control participants (2.1%), one reduction (not significant) of 18%.

The most comprehensive cross-country study of masks for COVID-19 infection is a comparison of policy changes, such as social distancing, travel restrictions, and wearing masks, in 41 countries. It found that introducing a mask-wearing policy had little impact, but mask policies were mostly introduced after social distancing and other measures had already been put in place.

The conversation, the author has provided What could reduce the effect of the masks?

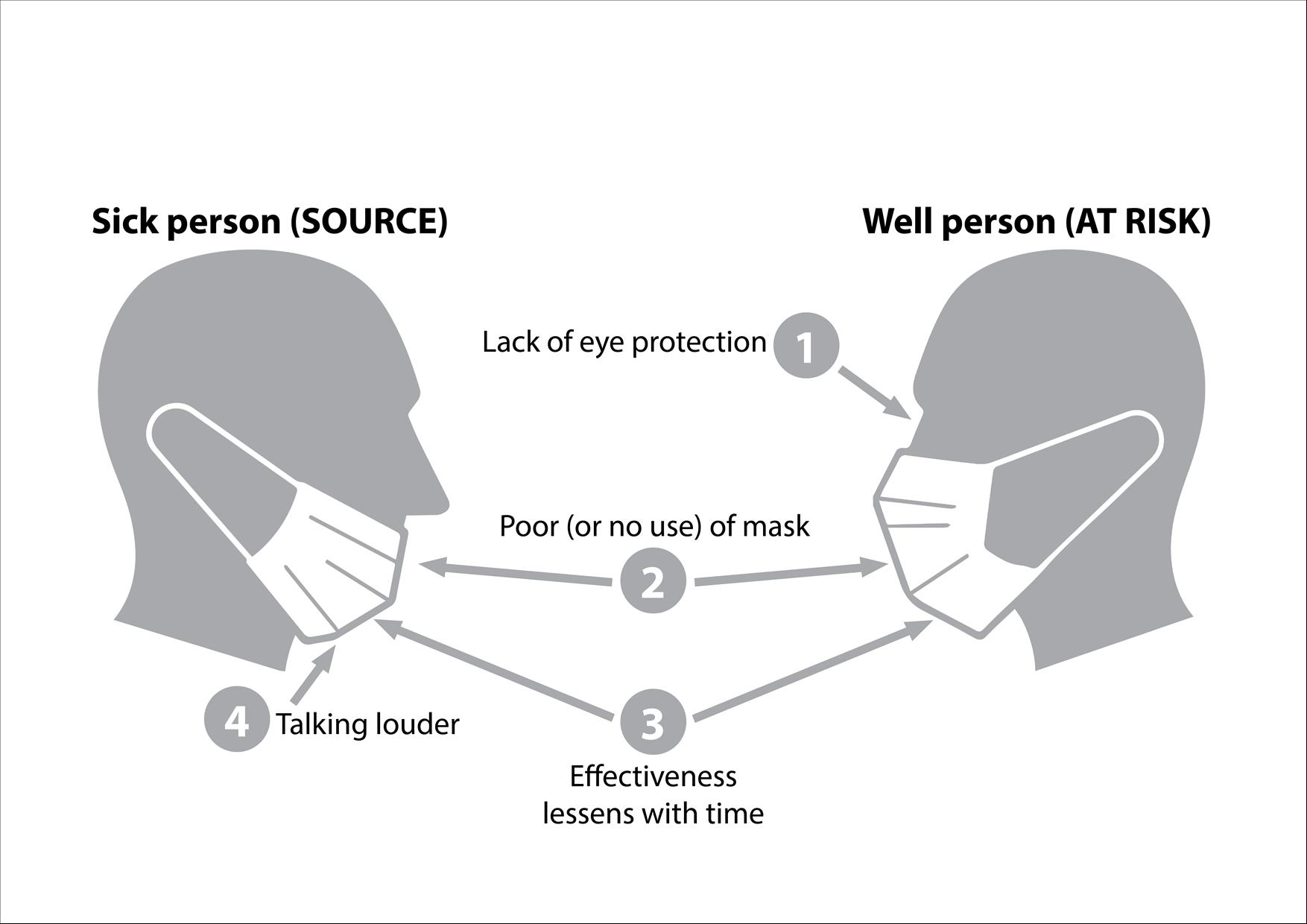

Why might masks not protect the person wearing them? There are several possibilities. Standard masks only protect the nose and mouth incompletely in the first place. Also, the masks don’t protect your eyes.

The importance of eye protection is illustrated by a study of community health workers in India. Despite protection from three-layer surgical masks, rubbing hands with alcohol, gloves, and shoe covers, 12 out of 60 workers developed COVID-19. Workers were then provided with face shields (providing eye protection) – in addition to the personal protective equipment (PPE) described above – and none of the 50 workers were infected despite the higher workload.

Why masks may fail to clearly protect others is more complex. Good masks reduce the spread of droplets and aerosols and therefore should protect others.

Things that could make masks less effective. Paul Glasziou, author provided

However, in our systematic review we found three trials that assessed how well wearing the mask protects others, but none of them found a noticeable effect. The two studies in families where one flu subject wore a mask to protect others found a slight increase in flu infections; and the third study, in college dormitories, found an insignificant relative reduction of 10%.

We do not know if the failure was the adhesion of the masks or the participants. Adherence was poor in most studies. In the tests very few people wear them all day (an average of about four hours for self-evaluation, and even less when observed directly). And this membership has declined over time.

But we also have little research on how long a single mask is effective. Most guidelines suggest around four hours, but studies on bacteria show the masks provide good protection for the first hour and are doing little for two hours. Unfortunately, we haven’t been able to identify similar research examining viruses.

Making masks mandatory only in crowded places, close contact environments, and confined, enclosed spaces can be more effective. Dan Himbrechts / AAP Is it better to focus the masks on the 3 C’s: covered, crowded and in close contact?

In addition to the completed Danish trial, another ongoing trial in Guinea-Bissau with 66,000 participants randomized as entire villages could shed some light as it tests the idea of source control. But given the millions of cases and billions of potential masks and mask wearers, more similar evidence is warranted.

We know that masks are effective in laboratory studies and we know that they are effective as part of personal protective equipment for healthcare professionals. But that effect appears to have diminished in community use. So, in addition to the evidence, new research is urgently needed to unravel each of the reasons why the lab’s effectiveness doesn’t seem to have translated into community effectiveness. We also need to develop ways to overcome the discrepancy.

Until we have the necessary research, we should be careful to rely on masks as a pillar to prevent community transmission. And if we want people to wear masks regularly, we might do better to target high-risk circumstances for shorter periods. These are generally places described by the “three Cs”: crowded places, environments in close contact and confined and enclosed spaces. These would include some workplaces and public transport.

We’re likely to be better off if we get high use of new masks in riskier settings, rather than moderate use everywhere.

Learn more: How should I clean my cloth mask?

MENAFN22112020000199003603ID1101167443

Legal Disclaimer: MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranties of any kind. We accept no responsibility for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the supplier above.

.

[ad_2]

Source link