[ad_1]

[ad_1]

When Toufic Al Rjula applied for asylum in the Netherlands four years ago, he delivered all the original copies of his documents to the immigration office: his passport, his driver's license, everything. "They even got my library card," he says.

When Toufic Al Rjula applied for asylum in the Netherlands four years ago, he delivered all the original copies of his documents to the immigration office: his passport, his driver's license, everything. "They even got my library card," he says.

His asylum application took two years to be processed, during which he had no legal proof of his identity. Al Rjula, a Syrian, had lived in the Netherlands for a work contract before seeking asylum. "I thought," I live in the Netherlands, I have a tax code and a dog, but I'm literally invisible ".

Born in Kuwait in the 1980s, Al Rjula had faced this problem before. During the Gulf War, his birth certificate was destroyed by fire in a government building in Kuwait City. This meant that the Dutch authorities had to put "unknown" as his city of birth on his driving license.

Based on his experiences and conversations with other Syrian refugees, he argues that many of these issues – slowness, lack of status, difficulty accessing services – could be solved simply by replacing our paper-based identity systems with something better. Thus, together with two co-founders, Khalid Maliki and Jimmy J.P. Snoek, Al Rjula started a start-up called Tykn in 2016, which uses blockchain technology to store the identity of refugees and migrants.

Explain that technology – which creates computer networks that form a secure information chain and requires access to digital keys – offers the potential for the permanent storage of vital information, which is not based on people who they must carry paper IDs with them that could be stolen or lost.

"By creating a global registry for public keys that can verify off-line identity data, we can create portable, private, and protected identities," says Al Rjula.

It is a complex concept. Blockchain technology was originally created for the completely different purpose of having a "decentralized" ledger – one that does not rely on a central server to gather and send information – for bitcoin transactions. It meant that every time the bitcoin was spent, it was recorded and therefore could not be spent twice because every transaction on the network would see the transaction. Since then, technologists have been fascinated by the additional applications that blockchain technology could have, in addition to the purchase and sale of cryptocurrency.

Especially for Al Rjula, he wants people's legal identities to exist independently of any paper document they carry when they flee conflict, persecution or natural disasters.

Most of Tykn's work is with NGOs working directly with refugees. For example, he is currently working on Project Zero Invisible Children, which aims to permanently certify the identity of children in conflict zones. Their partner organizations receive "digital signatures" and then assign portable identity cards through their usual processes, similar to UNHCR registration cards. The process will ultimately enable refugees and other stateless persons to access the global registry system via a smartphone.

"NGOs often have to make more recordings to more assistance programs, but in this way they only need to do it once for the same person," says Al Rjula. "Identity data is stored by its owners and sharing is done only with its consent".

Al Rjula is not the only one to notice the potential of this technology. The Rohingya Project is also working to develop blockchain-enabled identities. The project hopes to reach the estimated two million Rohingya stateless people living in South Asia and the Middle East with the goal of encouraging financial inclusion.

Muhammad Noor, a Rohingya community leader living in Malaysia, is leading the project. He is trained in computer science and has launched a series of projects aimed at helping his community, including a Rohingya media channel, a football team, and a computerized typeface for the Bengali dialect that speak Rohingya.

Explain that his goal is to create a global census of registered identities that will be recognized by financial institutions. "The companies that run Rohingya are all in cash," he says. "It's all in the dark economy, not in the mainstream economy, I want to bring them financial inclusion and this will be a starting point that will allow development." Right now, they have no credit history, they can not get loans, the banks do not know them. "

Another use of this technology could be a sort of "digital stamp" for people's professional qualifications. The Humanized Internet, a nonprofit organization created by former Cisco chief technology officer Monique Morrow, has won funding to accredit refugee skills and keep them as portable CVs. Likewise, the Norwegian startup Diwala has recently tested a decentralized platform to test the skills of people in Uganda, focused on helping young unemployed people.

The possibilities for blockchain technology are endless, especially for those working with refugees, and for those in the international development sector they write big. Giving people secure control over their information can help with finance, education and employment. However, some members of the aid community remain cautious, arguing that attention should remain focused on the search for lasting political solutions and not on technical patches.

Emre Korkmaz, a professor of migration and development at the University of Oxford, is not totally convinced of the virtues of the blockchain. Criticizes the new "power relations" that can emerge with the advent of new systems. For example, if blockchain technology is delivered in a field where refugees are essentially a captive audience, they may feel that they do not have the power to refuse to allow their personal data to be collected.

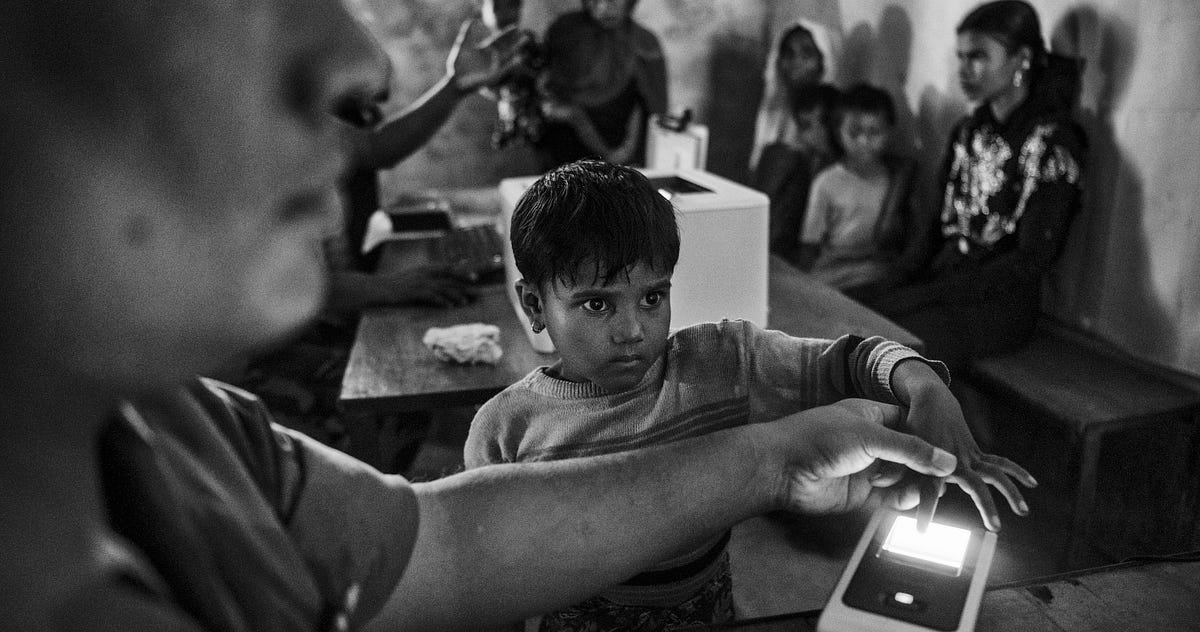

Some UNHCR programs are based on the collection of biometric data through a scan of iris. But Korkmaz says that some refugees have expressed health concerns about the scanning of their irises. However, if refugees want to access services, they have no choice but to consent. (Privacy concerns are one of the reasons why Tykn does not use iris scans in its technology, in particular, does not have a way to store biometric data on an individual's devices, and it would instead be stored centralized.)

Korkmaz is also concerned about the use of refugees' personal information. "What are the measures to prevent the technology companies that develop these programs from using this data for their business interests?" He asks. "Refugees are informed about the fate of [their] data?"

These questions are in the minds of those who develop digital identity technology. Adithya Pradeep Kumar works for Procivis, a Swiss technology company that has piloted the technology in Switzerland and has collaborated with the Rohingya project. Kumar says he studied the digital identity program in his country, India, before joining Procivis, and learned a lot about the risks of privacy. "India is a pioneer in digitization services and has launched its digital identity program to simplify the process of granting grants, which in the past was extremely inefficient and expensive."

But Kumar adds that "the example of India was beset by many privacy concerns due to the biometric data contained in a central database." What we are trying to do is to decentralize this situation, so that the information is stored on the smart devices of the same citizens … design privacy must be kept in mind as a fundamental principle ".

Al Rujla recognizes that this nascent technology faces a series of challenges before it can be fully adopted and operational. "And if the refugee loses his phone, how can they recover their data? What if there are no Internet connections? Can it work offline? Can it be hacked? There are so many questions," he says. "But it's all technical challenges that we have the ability to solve, none of which is the biggest challenge that is being adopted, it's building trust among refugees and NGOs."

Al Rujla hopes that his personal experience as a Syrian asylum seeker will help build this trust. "We can tackle the case through my story – showing people who have been built for refugees by refugees."

[ad_2]Source link