[ad_1]

[ad_1]

Blockchain and cryptocurrency, fraud management and cybercrime, fraud risk management

Researchers say blockchain presents more problems than it solves

Jeremy Kirk (jeremy_kirk) •

November 17, 2020

Blockchain technology, for all its cryptographic intelligence, has often been derided as the solution it’s looking for a problem.

See also: Ignite ’20: a preview of the conference

Bitcoin, which is built on blockchain, thrives as a kind of alternative underground currency. And the flavors of blockchain technology are applied to business use cases, such as supply chain monitoring. But it’s still a wandering nomadic technology, never quite perfect, but fascinating and magical enough to grab attention.

Introducing a new system in an age of rampant misinformation and distrust can be risky even if it works perfectly and securely.

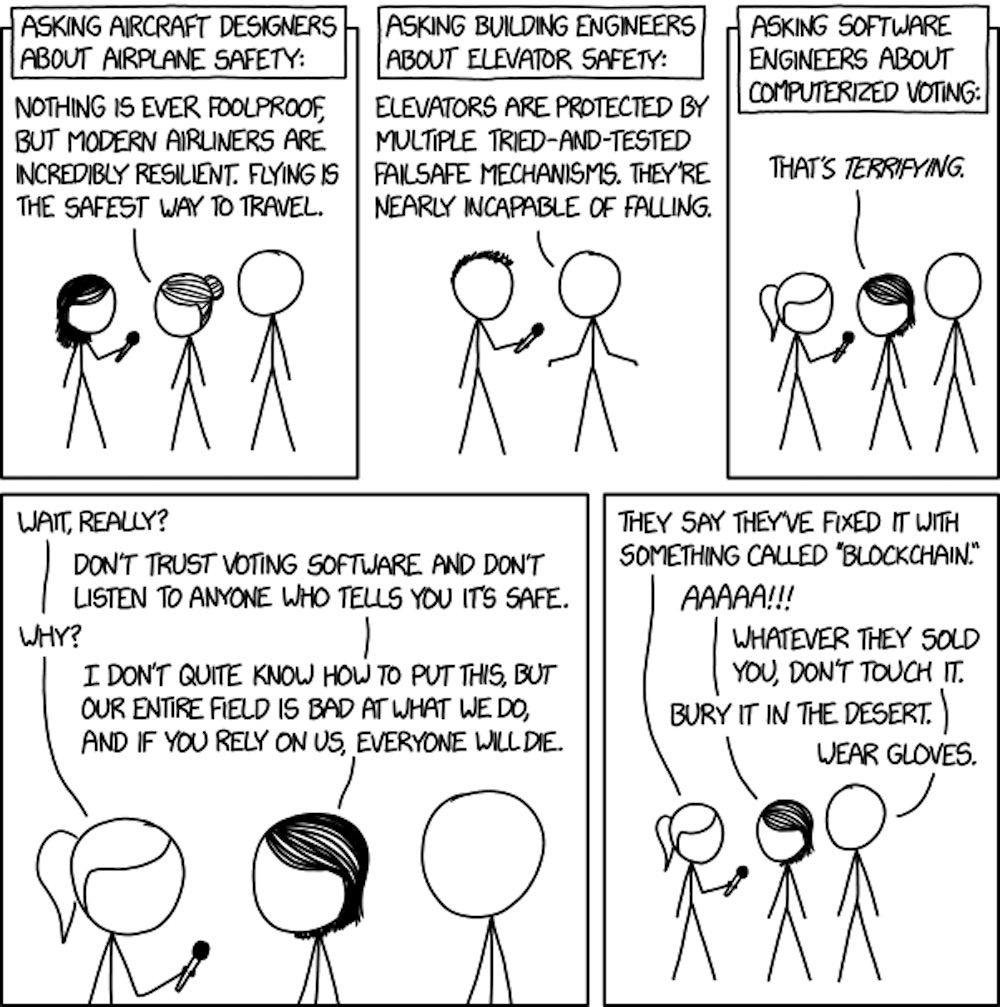

Some have suggested that the blockchain, a decentralized and distributed ledger, may be useful for voting. But in a new paper, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology claim a humorous cartoon from XKCD about potential blockchain voting products: “Whatever they sold you, don’t touch it. Bury it in the desert. Wear gloves.”

“Although current electoral systems are far from perfect, Internet and blockchain-based voting would greatly increase the risk of nationally undetectable election failures,” according to the document. “Perhaps counterintuitively, getting rid not only of obsolete voting equipment, but also of paper ballots risks ‘throwing the baby out with the bathwater’ and making elections much less safe.”

Risks increased

One of the main goals of an election is to convince the loser that he has actually lost. The use of blockchain-based technology for voting would further confuse the waters, the document argues.

One of the paper’s co-authors is Ron Rivest, one of three famous cryptographers credited with inventing the RSA algorithm, which revolutionized the public key cryptography that underpins much of transactional security on the Internet. The paper is co-authored by MIT’s Michael Spector, Neha Narula and Sunoo Park, who is also with Harvard.

“Although current election systems are far from perfect, blockchain would greatly increase the risk of undetectable election failures nationwide,” Rivest said in a statement. “Any increase in turnout would come at the cost of losing the significant certainty that votes were counted as they were cast.”

With a paper ballot, voters can see if their vote is correct. But votes cast entirely in software carry the risk that a single bug can make it appear that a vote has been registered correctly even if it has been modified.

Voting modernization is an appropriate discussion to have in the wake of the US elections. For decades, technologists have pondered how to use voting software to protect the principles of the sacred vote: secrecy but verifiable by voters and verifiable by electoral authorities.

It’s a tough nut to crack, but there are end-to-end encrypted systems, including STAR-Vote, that protect voting secrecy but ensure transparent counting and provide guarantees to voters. But the adoption of STAR-Vote was held back for commercial reasons, as a story in Wired magazine notes.

Blockchain Voting Problems

There are obvious frontline problems with the blockchain. Key management is one.

Bitcoin, for example, can be transferred using a private key. But if a private key is compromised – and there are many examples of cryptocurrency theft causing tears – that means, in terms of voting, someone else could vote. There is not only the problem of protecting the keys, but also of distributing them securely.

While stolen cryptocurrency is unfortunate, “elections have a much higher stakes than cryptocurrency. An attack on many cryptocurrency users would cause monetary losses, an attack on many voters can cause a change of government,” according to the newspaper.

Blockchains can also be compromised. In some systems they are powered by “miners” or nodes that perform the brute force calculations needed to complete a new block in the chain. But if some of these participants become harmful, it can wreak havoc.

Authorized blockchains, which by design do not allow unauthorized participants, are the logical solution. But licensed blockchains have fewer and more homogeneous servers, raising the “possibility that they can all be compromised,” the paper says.

“Authorized blockchains also do not address key management issues or the security of software and hardware on user devices,” the MIT experts write.

There are also new problems introduced by blockchains, they write. One is to coordinate bug fixes and deploy new software, which in a decentralized system may never be fast. More than a quarter of the bitcoin network is still vulnerable to CVE-2018-17145, discovered in 2018.

Blockchains simply don’t exist long enough to be used for mission-critical applications. Privacy-centric cryptocurrencies, such as Zcash and Monero, have new ways to protect transactional privacy – which may also have voting applications – but both have endured critical bugs, the researchers write.

“Another independent concern in using some blockchains for voting is the recklessness of using new distributed consensus protocols or cryptographic primitives for critical infrastructures until they have been well tested in the industry for many years,” they write. .

Paper cards: tried and true

I would also argue that there is a great barrier to public perception that has now been exacerbated by the last presidential election.

Cyber security, at least this time, wasn’t a problem in the election. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and a group of other agencies, non-partisan groups and voting equipment suppliers said last week that the US elections were the safest in US history.

There were minor errors and software glitches, as is normal in any election. But most states use paper voting systems or electronic systems that produce a paper record, which can be verified. And recounting is ongoing in some states.

However, allegations of widespread fraud continue to proliferate two weeks after the elections. This is despite US judges repeatedly dismissing alleged fraud cases for lack of evidence.

Reflect on how these voting integrity discussions would go with the intricacies of arcane technology like blockchain or any new electronic voting system that is a significant departure from the status quo. Introducing a new system in an age of rampant misinformation and distrust can be risky even if it works perfectly and securely.

Paper ballots are slow to process and slow to count. But it’s the best we have for both public trust and security.

.[ad_2]Source link