[ad_1]

The universe is a mysterious place. We don’t know why it exists and there are many unanswered questions about how. But what if it was created, on purpose, by an intelligent entity? Is there any way to find out?

In 2005, a pair of physicists proposed that if there was a Creator, they could have encoded a message in the background radiation of the Universe, left behind since light was first released to flow freely through space. This light is called the cosmic microwave background (CMB).

Now, astrophysicist Michael Hippke of the Sonneberg Observatory in Germany and Breakthrough Listen have gone in search of this message, translating the temperature changes in the CMB into a binary bitstream.

What he recovered appears to be completely meaningless.

Hippke’s paper describing his methods and findings has been uploaded to the arXiv pre-press server, (and therefore has yet to be peer-reviewed); the work includes the extracted bitstream so that other interested parties can study it for themselves.

The cosmic microwave background is an incredibly useful relic of the early Universe. It dates back to around 380,000 years after the Big Bang. Prior to this, the Universe was completely dark and opaque, so hot and dense that atoms could not form; protons and electrons flew around in the form of ionized plasma.

As the Universe cooled and expanded, those protons and electrons could combine to form neutral hydrogen atoms in what we call the age of recombination. Space became clear and light could move freely through it for the first time.

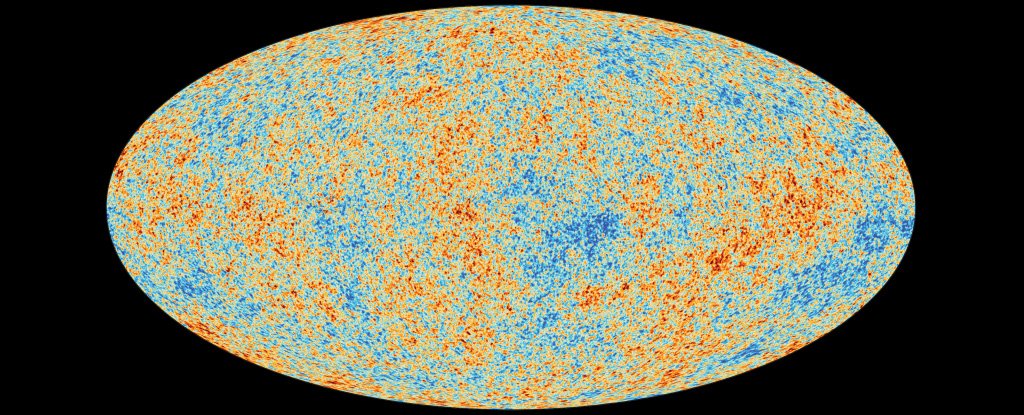

This first light is still detectable today, albeit very faintly, flooding all known space. This is the CMB. Since the early Universe was not uniform, the changes in density at the time of recombination manifest themselves today in very slight fluctuations in the temperature of the CMB.

Because of this ubiquity, theoretical physicists Stephen Hsu of the University of Oregon and Anthony Zee of the University of California, Santa Barbara argued – quite theoretically – that the CMB would be the perfect billboard on which to leave a message that would be been visible to all technological civilizations in the universe.

“Our work in no way supports the intelligent design movement,” they wrote in their 2006 article, “but it asks and attempts to answer the wholly scientific question of what medium and message might be IF there was indeed a message.”

They proposed that a binary message could be encoded in the temperature changes in the CMB. This is what Hippke attempted to find: first by addressing the claims made by Hsu and Zee, and then by using the data to try to find a message.

“[Hsu and Zee’s] The assumptions were, in the first place, that some higher Being had created the Universe. Second, that the Creator actually wanted to inform us that the Universe was created intentionally, “Hippke wrote.

“So, the question is, how would they send a message? The CMB is the obvious choice, because it is the largest billboard in the sky and is visible to all technological civilizations. Hsu and Zee continue to argue that a message in the CMB would be identical to all observers in space and time and that the content of the information can be reasonably large (thousands of bits) “.

Hippke found that there are several problems with these claims. The first is that the CMB is still cooling down. It started at around 3,000 Kelvin; now, 13.4 billion years later, it is 2.7 Kelvin. As the Universe continues to age, the CMB will eventually become undetectable. It could take another 10 two-decillion years (1040), but the CMB will vanish.

Putting this aside, physicists discovered in 2006, in response to the Hsu and Zee paper, that the CMB is extremely unlikely to appear exactly the same in the sky to different observers in different locations. Also, Hippke argues, we can’t see the entire CMB due to the foreground emission from the Milky Way. And we only have one sky to measure, which has statistical uncertainty inherent in every cosmological observation we make.

Based on these constraints, Hippke estimates that the information content would be much lower than that proposed by Hsu and Zee: only 1,000 bits. This gave it a good framework for actually searching for the message.

The Planck satellite and the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) both observed and recorded temperature fluctuations in the CMB. It was from these datasets that Hippke extracted his bit stream, comparing the results of each dataset to find matching bits.

The first 500 bits of the message are shown below. The black values were identical in both Planck and WMAP datasets and are believed to be accurate with a probability of 90%. Values in red deviate; Hippke chose Planck’s values and they are accurate with only 60% probability.

(M. Hippke, arXiv, 2020)

(M. Hippke, arXiv, 2020)

Changing values, he found, did not improve the situation. Searching the online encyclopedia for whole sequences has not produced convincing results, nor has the data shifted to approximate the infinite future.

“I don’t find any meaningful messages in the actual bitstream,” Hippke wrote.

“We can conclude that there is no obvious message in the CMB sky. However it is not clear if there is (there was) a Creator, if we are living in a simulation or if the message is printed correctly in the previous section, but we cannot understand it.”

Regardless of whether any of these options are valid or not, the CMB has a lot more to tell us, as was beautifully noted in a 2005 response to Hsu and Zee.

“The CMB sky encodes a great deal of information about the structure of the cosmos and perhaps the nature of physics at the highest energy levels,” wrote physicists Douglas Scott and James Zibin of the University of British Columbia.

“The Universe has left us a message of its own.”

Hippke’s article can be read in its entirety on arXiv.

.

[ad_2]

Source link