[ad_1]

Updated: November 28, 2020 10:04:21 pm

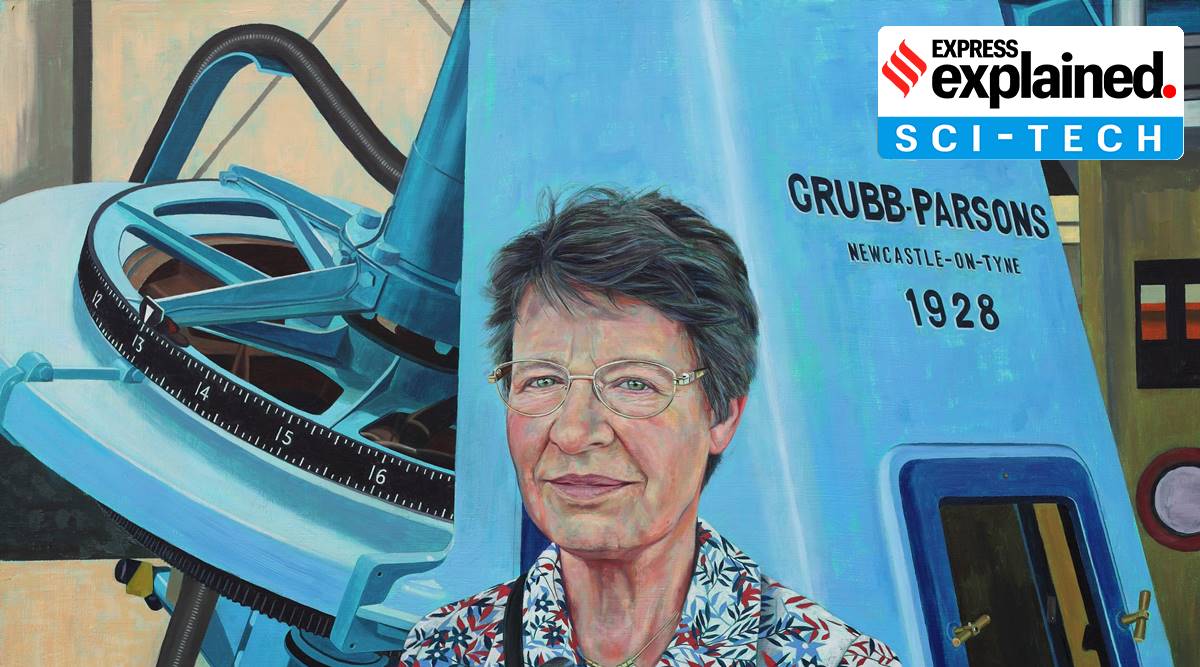

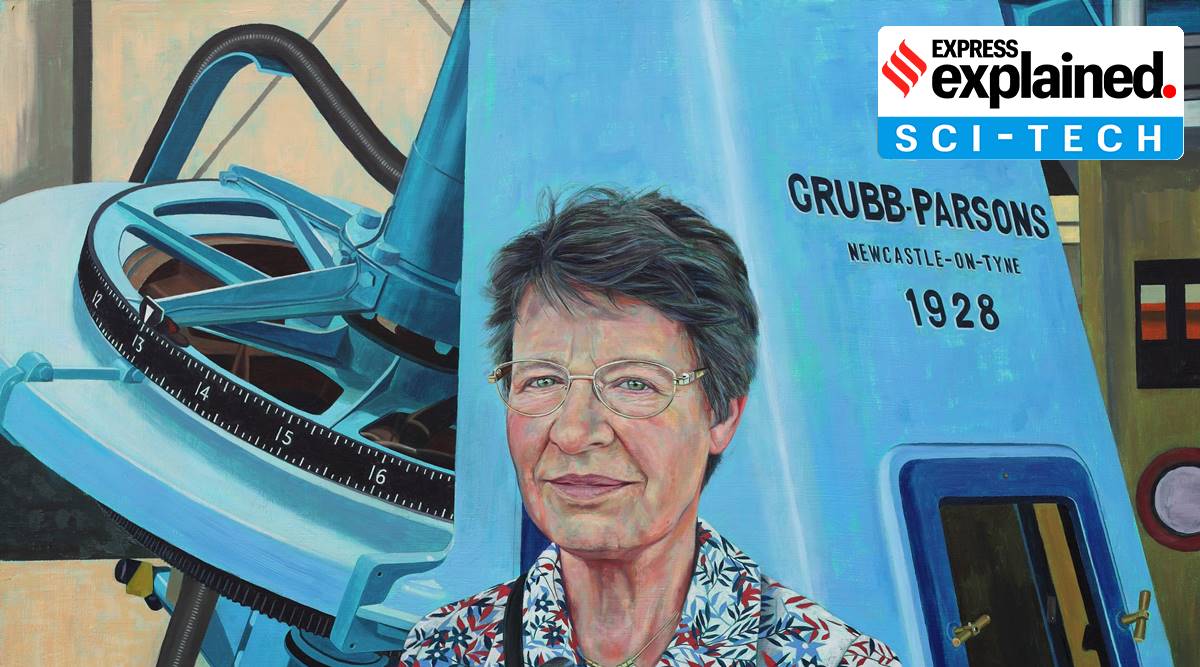

The portrait, an oil painting, was made by artist Stephen Shankland and marks 53 years since Burnell made his discovery. (Photo credit: The Royal Society via Stephen Shankland / Twitter)

The portrait, an oil painting, was made by artist Stephen Shankland and marks 53 years since Burnell made his discovery. (Photo credit: The Royal Society via Stephen Shankland / Twitter)

On Saturday, the Royal Society unveiled a new portrait of astrophysicist Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell who is credited with discovering pulsars when she was a PhD student at Cambridge University.

The portrait, an oil painting, was made by artist Stephen Shankland and marks 53 years since Burnell made his discovery. The painting, commissioned by the Royal Society, is part of an ongoing project that aims to increase the number of female scientists represented in its art collection of fellows and presidents.

Who is Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell?

Burnell was born in Northern Ireland in 1943. After failing over 11 years, she went to a boarding school in York where she became passionate about physics. He completed his doctorate in radio astronomy at Cambridge University in 1969, after which he held various academic positions around the world. She was president of the Royal Astronomical Society from 2002 to 2004 and was the first woman to hold the position of president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh from 2014-2018.

Today the Royal Society is proud to unveil a new portrait of pioneer astrophysicist Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell, on the 53rd anniversary of her discovery of pulsars, aged just 24. The portrait is by artist Stephen Shankland. https://t.co/VrFrTNxHk5

Image © Stephen Shankland. pic.twitter.com/lOn5RL6LMF– The Royal Society (@royalsociety) November 28, 2020

Burnell discovered pulsars, which are rapidly rotating neutron stars that emit radiofrequency pulses, on November 28, 1967. Neutron stars are the result of a supernova explosion, which is when a star reaches the end of its life and dies. .

The discovery was recognized by a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1974 which was shared by two professors, Antony Hewish (Burnell’s supervisor) and Martin Ryle. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said at the time that Hewish received half the award “for his decisive role in the discovery of pulsars”.

At the suggestion that Burnell should win the Nobel Prize, he wrote in a 1977 article in the Annals of New York Academy of Sciences and which was also his after-dinner speech at the 8th Texas Symposium on Relativistic Astrophysics that, “I believe that it would belittle the Nobel Prizes if they were awarded to research students, except in very exceptional cases, and I don’t think this is one of them. “

📣 Express Explained is now on Telegram

The graph capturing the precise moment when the pulsars were discovered by Burnell was first showcased on International Women’s Day in 2019, marking the 200th anniversary of the Cambridge Philosophical Society (CPS).

How were pulsars discovered?

Burnell was a PhD student at Cambridge at the time and was working with her supervisor Hewish to make radio observations of the universe. He ended up discovering a pulsar using a vast radio telescope occupying a 4.5-acre area that had been designed by Hewish and joined him and the team of five as the construction of the telescope was about to begin. The telescope was built to measure the random brightness flickers of a different category of celestial objects called quasars.

It took more than two years to build the telescope, and the team began using it in July 1967. According to Burnell, they had sole responsibility for operating the telescope and analyzing its data output, which amounted to 96 feet of chart each. day, which she scanned by hand.

In his 1977 article, titled “Little Green Men, White Dwarfs, or Pulsars?” Burnell wrote that the history of pulsar discovery began in the mid-1960s when the interplanetary scintillation (IPS) technique was discovered. This technique involved the fluctuation in the emission of radio signals from a compact radio source such as a quasar and was chosen by Hewish to locate quasars. While analyzing the telescope’s output, Burnell saw that there were unexpected marks on the paper that were recorded approximately every 1.33 seconds.

In the history of radio astronomy, the signals observed by Burnell in 1967 were at the time the most suggestive of extraterrestrial life, described as being produced “by chance” by NASA. But according to Burnell, while the source of the radio signals was speculated to come from another civilization, the team “didn’t really believe it.”

The paper announcing the first pulsar was presented to the journal Nature on January 3, 1968 and published in February of the same year. In this article, the authors, which included Burnell and Hewish, described their observations as a “strange new class of radio sources” and proposed that the source could be a white dwarf or a neutron star.

.

[ad_2]

Source link